ISDT QUALIFYING DONT COME EASY

Sam Moses

THERE IS A popular bumper sticker in Oregon that says, “Tom Lawson McCall, Governor, on behalf of the citizens of Oregon, cordially invites you to visit Washington or California or Idaho or Nevada or Afghanistan.” That message, about as subtle as an oil slick, fortunately doesn’t reflect the attitude of all Oregonians, and certainly not that of the people of Weston (pop. 660). For the past three years Weston has been opening its doors and its collective heart to a couple hundred or so motorcycle racers who travel across the Northwest’s deserts and mountains to a sparsely-populated corner of the state to be brutalized at a pogrom called Bad Rock.

More precisely, the Bad Rock TwoDay AMA Qualifier for the International Six Days Trial. After past accusations that America’s ISDT team was chosen based on the political points rather than the bonus points a rider could score, this year the team was chosen—ostensibly—based on the riders’ performances in the six two-day qualifying trials, of which Bad Rock was the final. It was thus the last chance to make the 30-man team. That in itself made Bad Rock the most important qualifier, but even had it not been the last, it would have been special for another reason: atmosphere.

Weston is located about halfway between the equator and the North Pole, which may explain its schizophrenic climate, ranging from 30 degrees below zero in the winter to 120 degrees in the summer. It is only a few acres away from Athena, home of Hodaka, but its real claim to fame is the pea factory at the north end of town.

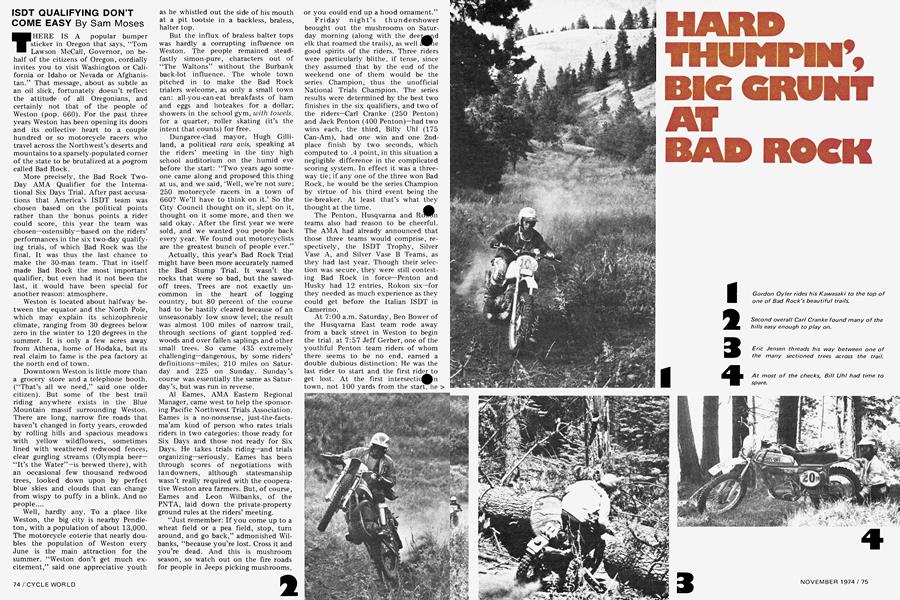

Downtown Weston is little more than a grocery store and a telephone booth. (“That’s all we need,” said one older citizen). But some of the best trail riding anywhere exists in the Blue Mountain massif surrounding Weston. There are long, narrow fire roads that haven’t changed in forty years, crowded by rolling hills and spacious meadows with yellow wildflowers, sometimes lined with weathered redwood fences, clear gurgling streams (Olympia beer— “It’s the Water”—is brewed there), with an occasional few thousand redwood trees, looked down upon by perfect blue skies and clouds that can change from wispy to puffy in a blink. And no people....

Well, hardly any. To a place like Weston, the big city is nearby Pendleton, with a population of about 13,000. The motorcycle coterie that nearly doubles the population of Weston every June is the main attraction for the summer. “Weston don’t get much excitement,” said one appreciative youth as he whistled out the side of his mouth at a pit tootsie in a backless, braless, halter top.

But the influx of braless halter tops was hardly a corrupting influence on Weston. The people remained steadfastly simon-pure, characters out of “The Waltons” without the Burbank back-lot influence. The whole town pitched in to make the Bad Rock trialers welcome, as only a small town can: all-you-can-eat breakfasts of ham and eggs and hotcakes for a dollar; showers in the school gym, with towels, for a quarter, roller skating (it’s the intent that counts) for free.

Dungaree-clad mayor, Hugh Gilliland, a political rara avis, speaking at the riders’ meeting in the tiny high school auditorium on the humid eve before the start: “Two years ago someone came along and proposed this thing at us, and we said, ‘Well, we’re not sure; 250 motorcycle racers in a town of 660? We’ll have to think on it.’ So the City Council thought on it, slept on it, thought on it some more, and then we said okay. After the first year we were sold, and we wanted you people back every year. We found out motorcyclists are the greatest bunch of people ever.”

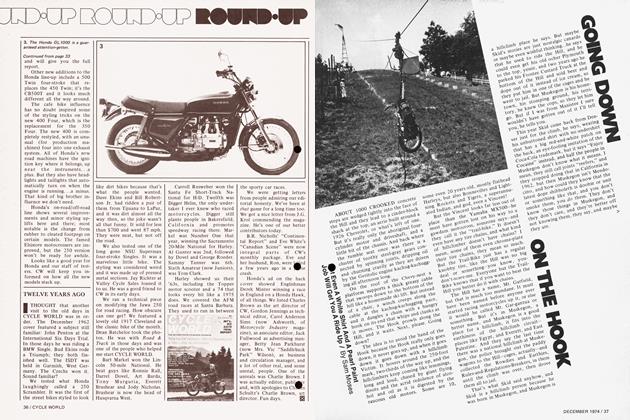

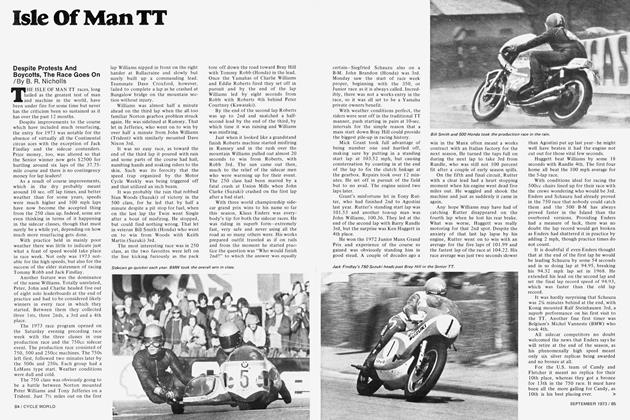

Actually, this year’s Bad Rock Trial might have been more accurately named the Bad Stump Trial. It wasn’t the rocks that were so bad, but the sawedoff trees. Trees are not exactly uncommon in the heart of logging country, but 80 percent of the course had to be hastily cleared because of an unseasonably low snow level; the result was almost 100 miles of narrow trail, through sections of giant toppled redwoods and over fallen saplings and other small trees. So came 435 extremely challenging—dangerous, by some riders’ definitions—miles; 210 miles on Saturday and 225 on Sunday. Sunday’s course was essentially the same as Saturday’s, but was run in reverse.

AÍ Eames, AMA Eastern Regional Manager, came west to help the sponsoring Pacific Northwest Trials Association. Eames is a no-nonsense, just-the-factsma’am kind of person who rates trials riders in two categories: those ready for Six Days and those not ready for Six Days. He takes trials riding—and trials organizing—seriously. Eames has been through scores of negotiations with landowners, although statesmanship wasn’t really required with the cooperative Weston area farmers. But, of course, Eames and Leon Wilbanks, of the PNTA, laid down the private-property ground rules at the riders’ meeting.

“Just remember: If you come up to a wheat field or a pea field, stop, turn around, and go back,” admonished Wilbanks, “because you’re lost. Cross it and you’re dead. And this is mushroom season, so watch out on the fire roads for people in Jeeps picking mushrooms, or you could end up a hood ornament.”

Friday night’s thundershower brought out the mushrooms on Saturday morning (along with the deei^^id elk that roamed the trails), as well H^e good spirits of the riders. Three riders were particularly blithe, if tense, since they assumed that by the end of the weekend one of them would be the series Champion, thus the unofficial National Trials Champion. The series results were determined by the best two finishes in the six qualifiers, and two of the riders—Carl Cranke (250 Penton) and Jack Penton (400 Penton)—had two wins each, the third, Billy Uhl (175 Can-Am), had one win and one 2ndplace finish by two seconds, which computed to .4 point, in this situation a negligible difference in the complicated scoring system. In effect it was a threeway tie; if any one of the three won Bad Rock, he would be the series Champion by virtue of his third event being the tie-breaker. At least that’s what they thought at the time.

The Penton, Husqvarna and Rearen teams also had reason to be cheerful. The AMA had already announced that those three teams would comprise, respectively, the ISDT Trophy, Silver Vase A, and Silver Vase B Teams, as they had last year. Though their selection was secure, they were still contesting Bad Rock in force—Penton and Husky had 12 entries, Rokon six—for they needed as much experience as they could get before the Italian ISDT in Camerino.

At 7:00 a.m. Saturday, Ben Bower of the Husqvarna East team rode away from a back street in Weston to begin the trial, at 7:57 Jeff Gerber, one of the youthful Penton team riders of whom there seems to be no end, earned a double dubious distinction: He was the last rider to start and the first rider to get lost. At the first intersectie^^n town, not 100 yards from the start, he turned the wrong way and rode over the hill and out of sight. Two minutes later he came back with redder-than-normal cheeks and a sheepish grin, and rode through town to cheers.

HARD THUMPIN', BIG GRUNT AT BAD ROCK

Despite young Gerber’s early difficulties, the problem was not getting into the woods, but getting out of them. Between the start and the first check there was one section whose name gives a clue to its purpose: Deadman’s Pass. Fortunately, everyone got through Deadman’s Pass alive, but soon thereafter came a heavily-wooded 45-mile loop, run twice, and the logs and trees on the trail began to raise the score of broken feet and twisted ankles. At the afternoon checks a cane salesman could have made enough to retire at 40.

The worst injury on the first morning—and the worst of the entire trial— was a broken back suffered by Lieutenant Bill Hofman of the Fort Hood Army team. Two vertebrae were crushed, a serious but not crippling injury. “If it had been a sergeant, he probably would have gotten up and walked away,” wisecracked one ex-draftee.

Along that loop came the five-mile timed special test, with which there were two problems: (1) Because the tests came so early in the day, the inexperienced trials riders had yet to drop out, (2) which wouldn’t have automatically been disastrous, except the special test section was as narrow as the rest of the trail. There were few riders with clean special test runs—many of the faster riders had to wait for traffic—but at least the disadvantage, if not the luck, was the same for everyone.

By the end of the day it was perfectly clear that the Bad Rock Trial was living up to its name. Like any rugged trial, the first day had separated the conditioned and prepared riders from the dabblers. Forty-seven riders were still on gold medal time, only a few more than earned gold medals for both days in last year’s trial. The most heartbreaking story of those losing their gold on the first day was Ben Bower’s. Bower, a 1973 ISDT gold medalist and member of the top Husky team, had been riding perfectly all day. His special test time total had been fastest by nearly 20 seconds, and he stood a good chance of pulling an upset overall win. But fatigue, as much mental as physical, thwarted him in a creek just a couple hundred feet from the end of the day’s 210 miles.

The final trail meandered along the creek before it shot up to the street and the finish, but between the creek and the street there was a six-foot-high dirt bank. Since Bower was the first rider in, there was no groove on the bank; he got his wheel to the top, but misjudged its steepness and fell back into the creek, stalling the engine of his 400 Husky. For more than 20 minutes he stood shin-deep in water kicking and fiddling in frustration as the crowd that had been gathered for the finish encouraged him, knowing, of course, that ISDT rules forbid any assistance. Finally the Husky started, and with a roar from the crowd he splashed out of the water and over the finish line. In the impound area he discovered that his choke cable had been pulled out and caught on the top of the carburetor, closing the choke. The agony of defeat....

Before Bower’s bubbles had settled, his spot in the creek was taken by Joe Barker, another promising young Penton rider some predict will be America’s best before long. Fortunately, Barker’s episode was more comedy than tragedy. His 175 Penton had drowned to a sputter at the base of the bank, and as the engine died he heard the timer at the finish announcing the minutes on the clock. Barker’s number was 21, and the timer was on 17. Barker kicked... 18...furiously...19. He put in a new plug. Twenty. He kicked some more. Twenty-one. His eyes showed frantic desperation. “Twenty-one-and-a-half,” shouted a Penton crew member. The Penton coughed and died. Kick, kick, it started! Barker held the throttle wide open and exploded out of the creek and up the bank, blasting bystanders with a shower of water and mud. He made it with about 10 seconds to spare, still on gold medal time.

But there was yet more melodrama at the finish, this time starring Jim Hollander, a never-say-die Rokon rider. Twenty miles earlier, Hollander’s rear tire had gone flat, and he had tried to ride it out. But the tire wouldn’t stay on the Rokon’s magnesium rim, so he had to pull the tire off altogether. Eleven miles from the finish, at a highway crossing called Pea Road, Hollander was already withered from pushing the heavy, clutchless Rokon (which is about as easy to push as a plow), so he took time out to collapse under the 90-degree sun.

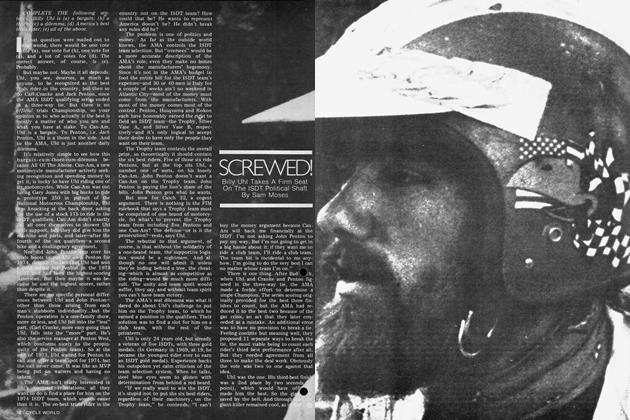

But the worst was yet to come; the last 11 miles made up the slowest, rockiest, steepest, meanest section of the day. Somehow Hollander plowed his way over the rocks, down the creek—all on a badly-mangled rear rim—and up the bank. When he saw the finish banner, his jubilance got the best of him, and he squirted the throttle of the Rokon... unfortunately just as the rim dropped in a pothole, which sent him and the rubberless Rokon down the street on their sides. But you can’t keep a determined man down—especially not after he had already come through what Hollander had—so he picked up the bike and clunked across the finish. The next morning in the 15-minute maintenance period before the start, Hollander strapped a new tire on his knobby rim with radiator hose clamps, but didn’t get very far before the tire fell off again and his Bad Rock Trial was over. Early Sunday morning, the previous day’s scores were posted near the impound, a concrete basketball court— Weston’s ansv/er to the parc fenne. Carl Cranke and Billy Uhl were^^th still on gold, and their combined time in the special tests was identical. Considering the variables, such as the traffic and Uhl’s getting off course and Cranke’s getting a flat front tire, their tie was mostly coincidental. But coincidental or not, it meant that the series Championship would be decided on the final day of the final trial. And Jack Penton, the third man in the running, was only 20 points behind. With his powerful 400 Penton, he could possibly make up that difference should Sunday’s special test section be fast.

But it wasn’t. Sunday’s special test was on a twisty, rocky, uphill, downhill stretch of Oregon goat trail. The combination of Uhl’s determination, confidence, consistency and absolute concentration, and Cranke’s bruised shoulder from a fall on Saturday—alth^^h Cranke certainly didn’t use that excuse—enabled Uhl to put together two special test times, each 12 seconds faster than Cranke’s, and take the overall win by 24 points. Jack Penton was 3rd overall. The series thus ended in a three-way tie.

Of the 130 starters, there were 51 finishers, 28 of them with gold medals. There is an ISDT axiom that defines a good trial as one in which 50 percent finish and 25 percent earn gold medals, so Bad Rock at least proved it was good—or bad—enough to challenge the best trials riders in America. As if anyone had any doubts.

(Continued on paqe 91)

Continued from page 77

¥| he five previous qualifiers were at Fort Hood, Texas; Picayune, Mississippi; Barstow, California, Trask Mountain, Oregon; and Potosi, Missouri. Since only the best two finishes counted it wasn’t critical that a rider ride all six, thus easing the financial burden since ISDT is an amateur activity.

Fort Hood was the planned sight for the 1973 American ISDT that was eventually held in the Berkshires. The course was contained entirely upon the sprawling Army base, and for all practical purposes the Army sponsored the event. Penton saturated the team entries, as it did at all the qualifiers. Carl Cranke led the way for the Penton team, in the absence of Tom and Jack Penton, who were at the Curley Fern National Enduro. Second was Malcolm Smith, who lost 50 points on both days when he had to push-start his 250 Husky each morning; but Cranke still would have been the winner had Smith not lost the 100 points. Third was Jim Hollander, having his first ride on the factory Rokon after riding the 1973 ISDT on a Triumph. Billy Uhl took 6th overall on a stock Can-Am, his first major trial since switching from Penton.

In one week the trialers went from the dust of Texas to the mud of Mississippi. But to call the stuff that submerged the Picayune qualifier “mud” would be too kind; actually, it was more of a fast-hardening black quicksand. Eighteen inches of rain in less than two weeks made most of the trails a series of bottomless mudholes. Few riders even made it to the first check on time, so AÍ Eames loosened up the schedule. Still, by the end of the first day only 28 of the 125 starters were left, and only seven of them were on gold. On the second day Eames cut out the near-to impassable swamp sections and reduced the mileage to 65— about 100 miles less than an average Six Days section—in addition to throwing out the special test altogether.

When the confusion was sorted out, the winner was Uhl, over a disappointed Jack Penton, who had the fastest Saturday special test time, but had made a mental error at one of the checks. As a result, he was late by one minute, losing his gold medal. The Picayune qualifier had defeated more than its share of riders, and it had been a test to the extreme; all but three of the finishers were ISDT veterans.

Back to the dust and rocks for qualifier number three—this time at Barstow, California, in the Mojave desert. By now the pattern of DNFs was set: a whopping number on the firstday to sort the veterans from the novices, and then only a few on the final day. At Barstow the toll was 121 retirements out of 155 starters on Saturday, only six more on Sunday, for a total of 28 finishers.

(Continued on page 94)

Continued from page 91

The crusher at Barstow was the heat. The best lOOcc trials rider in the country, Dane Leimbach, passed out from paddling his little Penton in the soft sand. Quitting with broken bones were Dave Mungenast (a hip), and Jack Penton (a couple of toes). As at Picayune, the second day was shortened because of the ruggedness of the first day.

Overall, it shaped up mostly as a contest between what were so far the two winning riders in the series and two of the top desert racers in District 37: Cranke and Uhl, and Cordis Brooks and Mark Adent. In the special tests Cr^^/e was 47 seconds faster than BroolÄln the first day and 39 seconds slower on the second day, so his faster combined time preserved the overall win for him, his second in as many qualifiers as he entered. Slipping impressively into 3rd, to separate the Cranke-Brooks/AdentUhl matches was Bultaco’s Mike Hannon.

Adent, on a 175 Penton, and Uhl, on the factory 175 Can-Am, also split fast times for the special tests, but Adent’s combined time was 34 seconds faster, so he took 4th overall to Uhl’s 5th. After the trial, Uhl and Adent made a deal: Adent would give Uhl lessons in desert riding, and Uhl would give Adent lessons in woods riding.

Round four, and the first trip to the Northwest: Trask Mountain, Oregon.

Enter Jack Penton on his big 400.

Trask Mountain was the easij^^of the qualifiers to that point. Aft^^the first day, the five leading riders were within 23 seconds of each other: Penton, Joe Barker (125 Penton, -6 seconds), Uhl (-13), Malcolm Smith (-21), and Cranke (-23). Cranke reversed the score on the second day but not by enough to make up the 23-second difference. In the closest finish yet, Jack Penton took 1st overall, with Uhl just two seconds back and Cranke only six more behind.

Penton did it again at Potosí, Missouri. His second win in a row tied Cranke in the series and set the stage for the pressure-filled Bad Rock qualifer. And again it was a close one for the top three: Penton won by 13 seconds, over Cranke this time, with Uhl only eight more seconds behind.

Potosi’s peculiarity was more mud, but unlike the black gluey m^fc of Picayune, Potosi’s mud was red and greasy. Fortunately, it made thin^^miteresting, but not impossible. What really made Potosi provocative was Joe Barker—4th in the series—appearing on a new 175 Penton. His assignment was to topple Uhl so that Jack Penton or Cranke would have an easier shot at the Championship. But Uhl had finally talked Can-Am into more support, in the form of a new machine, and he held off Barker’s challenge by 17 seconds.

(Continued on page 98)

Continued from page 94

So the stage was set for the final qualifier. Uhl’s victory at Bad Rock officially only moved him into the three-way tie for the series Championship, but at Weston he was generally accepted as the unofficial Champion, which meant the best trials rider in the

United States. And so it was, Champion or not, Uhl, the relative privateer, beating the odds and the might of the Penton effort. ^^3

HE UNITED STATES teaiÄssignments for the 49th International Six Days Trial held in

Camerino, Italy, the riders’ qualifying series positions and their machines are as follows:

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMotorcycles, Rehabilitation And A Funky Jamboree

November 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

November 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

November 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Features

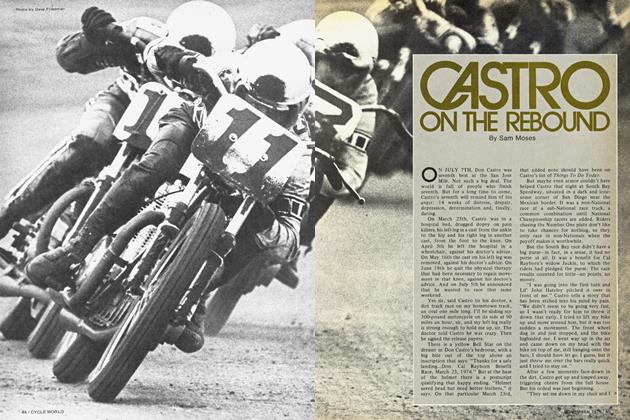

FeaturesCastro On the Rebound

November 1974 By Sam Moses -

Competition

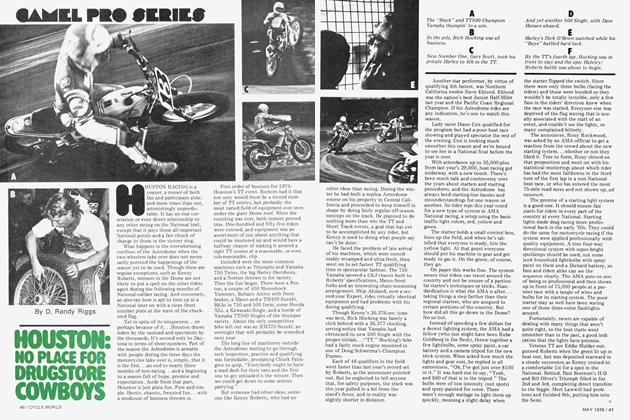

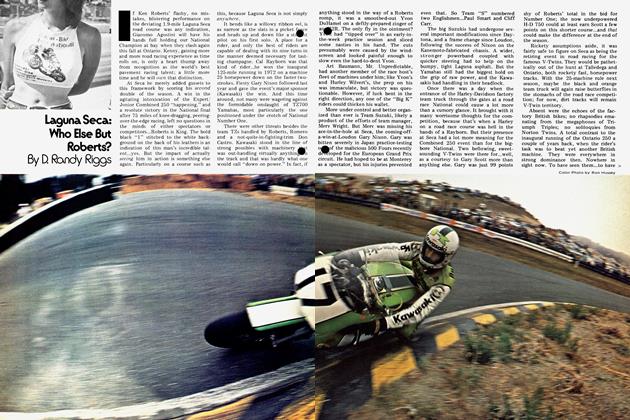

CompetitionLaguna Seca: Who Else But Roberts?

November 1974 By D. Randy Riggs