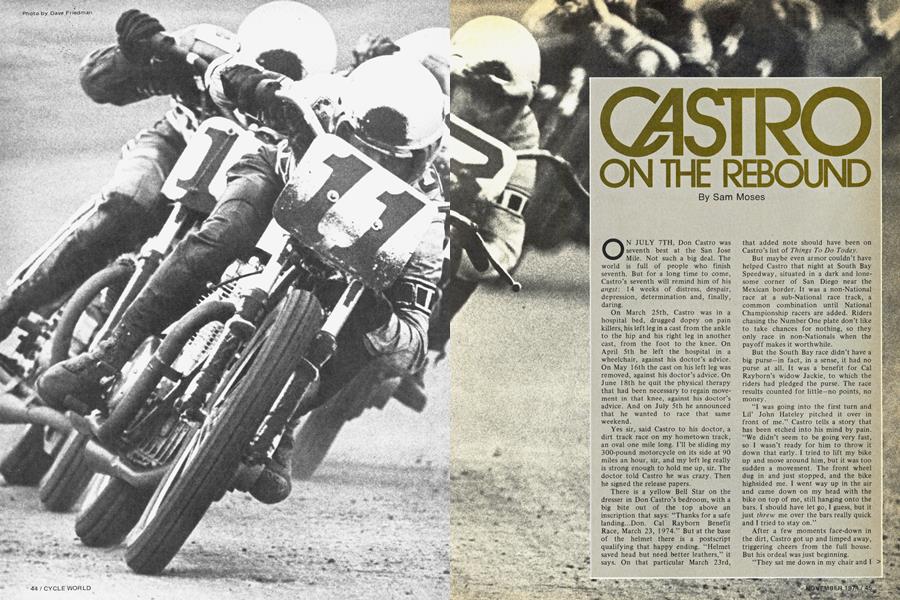

CASTRO ON THE REBOUND

Sam Moses

ON JULY 7TH, Don Castro was seventh best at the San Jose Mile. Not such a big deal. The world is full of people who finish seventh. But for a long time to come, Castro’s seventh will remind him of his angst: 14 weeks of distress, despair,

depression, determination and, finally, daring.

On March 25th, Castro was in a hospital bed, drugged dopey on pain killers, his left leg in a cast from the ankle to the hip and his right leg in another cast, from the foot to the knee. On April 5th he left the hospital in a wheelchair, against his doctor’s advice. On May 16th the cast on his left leg was removed, against his doctor’s advice. On June 18th he quit the physical therapy that had been necessary to regain movement in that knee, against his doctor’s advice. And on July 5th he announced that he wanted to race that same weekend.

Yes sir, said Castro to his doctor, a dirt track race on my hometown track, an oval one mile long. I’ll be sliding my 300-pound motorcycle on its side at 90 miles an hour, sir, and my left leg really is strong enough to hold me up, sir. The doctor told Castro he was crazy. Then he signed the release papers.

There is a yellow Bell Star on the dresser in Don Castro’s bedroom, with a big bite out of the top above an inscription that says: “Thanks for a safe landing...Don. Cal Rayborn Benefit Race, March 23, 1974.” But at the base of the helmet there is a postscript qualifying that happy ending. “Helmet saved head but need better leathers,” it says. On that particular March 23rd,

that added note should have been on Castro’s list of Things To Do Today.

But maybe even armor couldn’t have helped Castro that night at South Bay Speedway, situated in a dark and lonesome corner of San Diego near the Mexican border. It was a non-National race at a sub-National race track, a common combination until National Championship racers are added. Riders chasing the Number One plate don’t like to take chances for nothing, so they only race in non-Nationals when the payoff makes it worthwhile.

But the South Bay race didn’t have a big purse—in fact, in a sense, it had no purse at all. It was a benefit for Cal Rayborn’s widow Jackie, to which the riders had pledged the purse. The race results counted for little-no points, no money.

“I was going into the first turn and Lil’ John Hateley pitched it over in front of me.” Castro tells a story that has been etched into his mind by pain. “We didn’t seem to be going very fast, so I wasn’t ready for him to throw it down that early. I tried to lift my bike up and move around him, but it was too sudden a movement. The front wheel dug in and just stopped, and the bike highsided me. I went way up in the air and came down on my head with the bike on top of me, still hanging onto the bars. I should have let go, I guess, but it just threw me over the bars really quick and I tried to stay on.”

After a few moments face-down in the dirt, Castro got up and limped away, triggering cheers from the full house.

But his ordeal was just beginning.

“They sat me down in my chair and I put my legs up on another, with ice packs on them. I still didn’t want to be injured, so I said to everyone, ‘I’m okay, I’m okay,’ but I really hurt. But b^he end of the race I couldn’t move....

“Kenny Roberts flew down for the race in his airplane with Jim Doyle, and they took me back north to Kenny’s house that night. They didn’t even have any aspirin or anything; I couldn’t sleep, and Doyle sat up with me all night. By morning I knew I was hurt bad, so I said, ‘It’s time to go to the hospital now!’ ”

The fractured and chipped right ankle and two broken ribs that the doctor diagnosed by that afternoon came as no surprise. But the really bad news was that all the lateral ligaments in Castro’s left knee were snapped like rubber bands. That evening Castro went into surgery. They drilled a hole in his kneecap and threaded the remaining ligaments from behind his knee through the hole, and reorganized his whole knee-jerk mechanism. Today thg^Jshaped scar almost surrounds his Mrecap, and he wears the scar like a cachet. He calls it the $ 6-million leg.

Castro’s chronicle of recovery is no more spectacular than that of many other professional motorcycle racers who have suffered serious injuries and have come back. At one time or another in their careers, they almost all have had similar experiences, many of them more than once. Even now, Gary Nixon and Mark Brelsford are agonizing through much the same sort of recovery.

But for Castro, who has at times been both underexposed and underrated, the knee injury couldn’t have come at a more inopportune time. At the beginning of this year, few people would have wagered against Yamaha’s Kenny Roberts repeating as National Champion, since he was riding high on a crest of confidence and was the l^^al odds-on favorite. But in a year ^ien everyone except Roberts was an underdog, Castro, the number two man on the Yamaha team, came off as the brightest of the dark horses. A handful of other riders had the talent, but lacked the equipment; only the Yamaha team had both.

Gene Romero, the third man on the Yamaha team, was a strong possibility, based on experience. Indeed, he was National Champion in 1970; but he needed to make a difficult transition from Triumph—a marque he had been next to all his racing life—to Yamaha. His experience on the unique Japanese racers—both the two-stroke road racer and the light-flywheeled dirt tracker— was next to nil. It would take several races for Romero to become as intimate with Yamahas as he had been with Triumphs, and in a close Grand Nat^Äal season, even a couple of races is sometimes too many.

So by the process of pre-season speculative elimination, if nothing else, Castro emerged as the man most likely to score on the slightest change of pace by Roberts. Although he was only 24, was in his fifth season as an Ex^rt, and he was overdue’. He had begun racing as a dirt tracker, but, like any good ol’ boy bred on Pirellis and steel shoes, he took to road racing in the auspicious manner endemic to your average American natural: He fell off the first time he ever got behind a fairing and finished 3rd on his second try. Oh yes—his second road race was the 1970 Daytona 200.

That was also his first big race as a factory Triumph rider. “When I was an Amateur I broke my ankle playing soccer with Nixon inside the Triumph warehouse in Baltimore. That’s how I got on the Triumph team—I think they were afraid I was going to sue them.” 1970 was a very good year to be a rookie —or a veteran, for that matter—and working for BSA/Triumph. The Britishers’ budget afforded deluxe ti^^ment all the way, and although the fringe benefits progressively dwindled throughout the next two years, life was still easy for the BSA boys throughout 1971.

But in 1972 the bottom of the budget fell out in Birmingham, and what was once a ten-man team suddenly became two: Romero and Dick Mann. Castro was cut, and Triumph was pounding on his door like bill collectors for his race bikes. The decision came too late for Castro (or any of the other BSA/Triumph riders) to look for another ride, so Castro endured, but barely survived, the 1972 season as a privateer.

It was an unkind shock. On his way to the first race of the year at Houston, his van, loaded to the vents with all his racing possessions, was ripped off while Ca^:o was inside a motorcycle shop. T^Pfiext day the empty van was found in a vacant lot, but the vacuum inside represented an uninsured $11,000 loss.

Six months later Castro’s missing Montesa short tracker set a record for a racing motorcycle ridden through a radar trap in downtown Los Angeles50 miles an hour in a 35 zone. The police apprehended the rider but couldn’t put enough evidence together for a conviction on anything more than a speeding ticket.

The theft was an augury that 1972 wasn’t going to be Castro’s year. He rode some of the dirt tracks on a private Triumph, missed all the road races but one (“No one would sponsor me; they all thought I was no good.”), tried and abandoned speedway. But the winter of 1972 brought the contract with Yamaha, and Castro responded by finishin^|th in the National Championship ai^Wvinning his first National—the San Jose Half-Mile.

It was a sure bet that 1974 would be Castro’s best y ear...barring disaster. At Daytona he had won the 250 race by passing Roberts at the finish line. The next day he had finished 4th in the 200-miler, from the most talent-packed field of road racers ever assembled on one piece of pavement. He couldn’t wait for the Anglo-American Match Races in April. Castro was, as he would say, pumped. But then came South Bay. And the recovery.

“For the first ten days they gave me a shot every three hours for the pain,” he recalls, “and I stayed wired all the time. They let me up and gave me a wheelchair after a couple days and I ran wide open around the halls and outside on the patio, which is normal for me, but they were afraid I was getting hooked on the stuff, so for the last two days the doctor told me I could drink all the wine I wanted. That was as good as the shots.”

Castro talked his way out of the hospital in 12 days, and went home to incubate in his fiberglass candy-blue metalflake stereo chair. With the stereo volume set at loud, the TV picture on but the volume off, and his plasterpacked legs spread straight out in front of him on a matching metalflake stool, he spent six weeks shooting darts while the blue devils stole 20 pounds from a 140-pound frame that couldn’t afford to weigh one dart feather less.

“At first it wasn’t too bad because I slept a lot from the pain pills, but when I ran out of pills I started to go crazy, mostly from the boredom. I had some crutches but they hurt my broken ribs. Every time I moved it killed me, so I didn’t move very much. T Love Lucy’ got to be the high point of my day.”

After a diet of darts and soap operas, Castro was ready to do anything to get the casts off. When the doctor agreed, Castro thought he was home free; but when the left cast was actually removed, he still couldn’t move his knee. Ligaments grow slower than bones, as he was finding out.

“So I had to take physical therapy. Every day for an hour they soaked me in a hot whirlpool, then they tugged and pulled on my knee. For the first week I couldn’t move it at all so they’d lie me down under this block contraption and try to stretch my leg back and forth; then they’d turn me over on my stomach and pull my leg up behind me. And while I’m lying there wanting to scream, they’re telling me how crazy I am to race motorcycles and how I should never race again.

“When I get home and my parents come by, my mother says, ‘Well, you had enough yet?’ That’s enough to get you down. But then Nixon calls and says I’ll forget all about the pain when I’m back on a motorcycle, and I knew he was right.” And now, as Nixon sits at home not even able to throw darts because both arms are in casts, it’s Castro’s turn to be the comforter instead of the comfortee.

After about a month, Castro had stretched almost 12 inches of movement out of his knee and had gone from 2xh pounds on the weight machine to 40, so he quit the formal therapy and started his own: tennis and bicycling.

“The computer in my brain hadn’t gotten together with the muscles in my new knee, and when I first played tennis I tripped myself a lot because my right leg took longer to get the message to move than my left. But finally it began to work, and I’m thinking ‘Hey, maybe I can race at San Jose,’ so I started hinting at the doctor. When I was in the hospital he told me that I would need therapy until at least September, and it was only June. Even he couldn’t believe my progress.”

On Friday, July 5, at 5:00 p.m., when the doctor was ready to go home for the weekend, Castro went to see him and persuaded him to sign the AMA release form. The doctor just shook his head as he signed.

But then doctors can’t quite understand what it means to be a racer. Nor had anyone at San Jose reckoned on seeing Castro suited up in his leathers, waiting impatiently at the infield gate for practice to start. But in order to get there he had had to do even more persuading—this time it was the manager of the Yamaha racing team, Pete Schick. Castro had called Schick that Friday evening. “Bring my bike to San Jose,” he said, “because I just got my release and I’ll be there.” Schick reluctantly agreed, but only if Castro promised to just practice. “Okay, I promise,” said Castro, “just a few laps to test out my leg.”

When the first practic'e session ended, Castro went directly back to the line without stopping at Go, and sneaked into the second session. And the third. And fourth. Between the second and third sessions Schick caught him. “Just what are you doing?” asked Schick, knowing what kind of answer he could expect.

(Continued on page 110)

Continued from page 47

“Just practicing, Pete, that’s all,” replied Castro innocently without raising his tinted visor, so Schick couldn’t look into his eyes, which showed an ebullience they hadn’t shown for more then three months. “Just practicing,” he said again, this time to the inside of his helmet.

Castro qualified (“Just to see if I’m still fast, that’s all, honest, Pete.”), and rode the heat race (“Just to get used to riding in traffic, that’s all, honest, Pete.”).

It almost was. His heat race had to be restarted twice because of hard first-lap crashes. After the second start, Larry Gino entered the third turn at 120, slid into the outside fence, and smacked it with a force that catapulted him 108 feet before he even hit the ground on the other side. He left a large chunk of one knee on the fence. He had been inches behind Castro at the time.

Everyone survived the first lap of the third start. Gary Scott and Mike Kidd broke away in the lead, and behind them Castro was scaring Schick to death by rattling handlebars with an aggressive rookie, Rob Morrison. On the third lap, Morrison charged underneath Castro in turn one. As he slid alongside Castro at nearly 100 mph, the long right footpeg on his Wood Norton hooked Castro’s leg away. Castro drifted wide in order to unhook his leg, but he was leaned over so far that by the time it came off Morrison's footpeg, it was on top of his own handlebar.

“ ‘God,’ I thought, ‘there goes my knee. What am I doing out here?’ ” But as quickly as that doubt flashed into Castro’s mind, it flashed back out again. He contorted his body back on the seat and the bike back into the groove, and he even managed to get a good ride out ot turn two. He caught Morrison down the back straight.

“I got in his draft, then pulled out and swooped by. When I did, I hit him with my fist on. his back as hard as I could. I don’t do anything like that very often, but he really made me moody. That number in turn one scared me, because l expected things to be a lot safer. I mean I was really trying to ride defensively-wasn’t sticking it in there like I normally do. I had to watch a lot of guys go under me in the corners because of it, and that’s hard for me.”

But Morrison apparently wasn’t impressed; for five more laps he kept moving on Castro. On the last lap, without pausing to hammer him on the back this time, Castro charged by Morrison for a solid 3rd in his heat. That was all it took; there was no stopping him from riding in the main event now. “I was getting ‘pumpederj and ‘pumpeder’,” he said.

The main event was largely a replay of Castro’s heat, but twice as long and twice as hairy. With Scott and Kidd in the lead for the entire 20 miles, Castro got caught in the thick of a five, six, and sometimes even seven-man battle for 5th place. He had conceded after the 10-lap heat race that he didn’t think his leg was ready for 20 laps at full steam, and on the twelfth lap of the main, he faded from leader of that pack to follower, losing four positions in as many turns.

But with about five laps to go, his second wind came. As if to kick caution in the teeth with his steel shoe, he clawed his way to the front of the group once more, dragging his left leg over the chunks in the track and knowing that with one wrong twist of his knee, they would be carrying him back to the therapist’s stretching block.

By the last lap, attrition had reduced the battle for 5th to four men—Castro, Morrison, Romero and Scott Brelsford. They came off the last turn almost abreast, with Castro on the outside, leading by no more than a couple of feet. In the drag race to the finish line, Morrison pulled out of Castro’s draft, inched ahead, and began moving over from the left side. Castro was being sandwiched.

He headed toward the outside fence until he could move no closer, his right footpeg digging into the dirt berm at the edge of the track and his handlebars almost knocking against the rail. He backed off. Brelsford, towed along by Morrison’s draft, just squeezed by at the finish line. On a day when he shouldn’t have been doing anything more strenuous than riding his bicycle around the block, Castro finished 7th in a knockdown, drag-out motorcycle race.

Immediately after the race there was a minor maelstrom. Romero jumped off his bike and marched after Morrison, meeting Chuck Palmgren along the way, who was waiting for Morrison. Romero’s father and Jim Rice joined them and formed row two of the punchout parade. (The main event was restarted after Rice and Lawwill were both knocked out on the first lap—by Morrison, contended Rice). Later, after what seemed like half the riders in the race had submitted a formal protest, Morrison was reprimanded by the AMA for rough riding.

Castro had as much reason as anyone to be surly about the situation, but while the hassle was at its hottest, he was back in his chair, smiling and signing autographs, and telling people how his knee squeaked now. He was just glad to be racing again.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMotorcycles, Rehabilitation And A Funky Jamboree

November 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1974 -

Departments

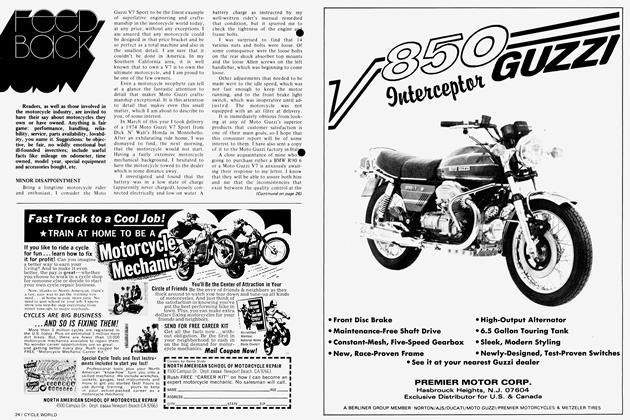

DepartmentsFeed Back

November 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

November 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Competition

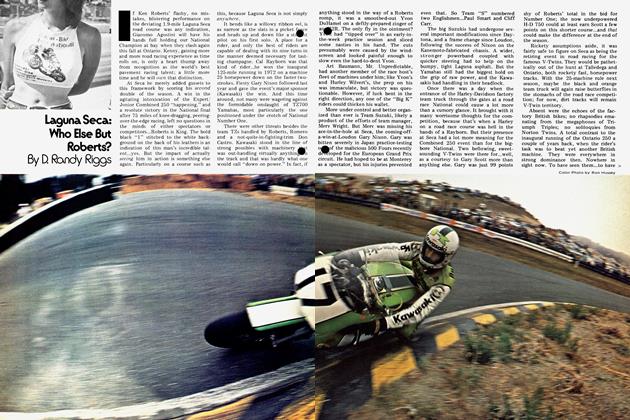

CompetitionLaguna Seca: Who Else But Roberts?

November 1974 By D. Randy Riggs -

Features

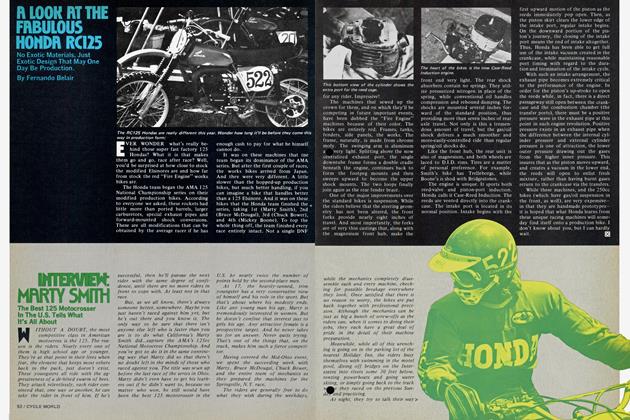

FeaturesA Look At the Fabulous Honda Rc125

November 1974 By Fernando Belair