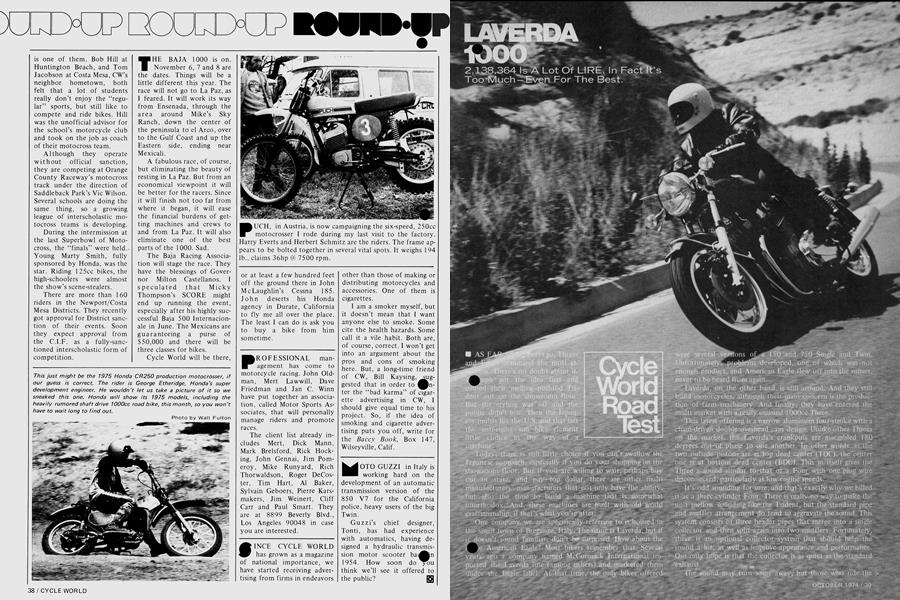

LAVERDA 1000

Cycle World Road Test

2,138,364 Is Lot Of LIRE. In Fact It's Too Much — Even For The Best.

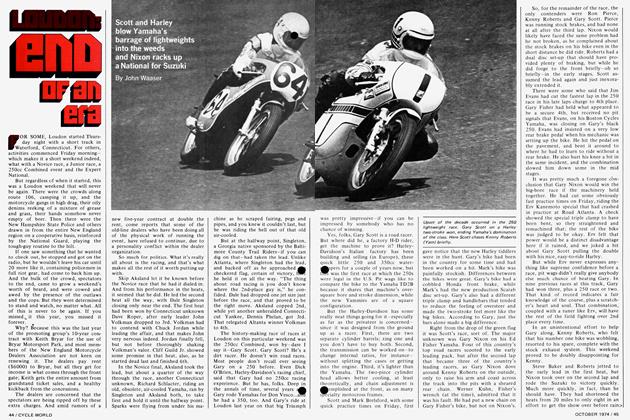

AS FAR AS big bores go, Threes and Fours command the most attention. Ther's no doubt about it. Triump got the idea first and rushed their mellow pushrod Trident out on the showroom floor. But the styling was off and the public didn't bite. Then the Japanese multis hit the U.S. and that left the anti-rising sun bike element little choice in the way of a machine.

ay, there is still little choice if you can't swallow the se approach, especially if you do your shopping on the snowroom floor. Bui if you are willing to wait, perhaps buy oui oi state, and pay top dollar, there are other multi manufacturers...manufacturers that not only have the ability, but also the time to build a machine that is somewhat unorthodox. And. these machines are built with old world craftsmanship, if that’s what you’re after. ;

One company we are specifically referring to is housed in the small town of Breganze, Italy. The name is Laverda, b|jt if CoesnT sound familiar, don’t be surprised. How about the <e American Eagle? Most bikers remember that. Several years ago a company named McCormack International imported the Laverda line (among others) and marketed them under the Eagle label. At that time, the only bikes offered

were several versions o¿ a 150 and 750 Single and Twin. Unfortunately, problems developed, one of which was not enough product, and American Eagle flew off into the sunset, never to be heard from again.

Ltverda, on the the~ 1~aiid i~s~jj~ w~j~4 And~ey still b1~L1U rn tou~.ych~s aittiough their iai~xn1ce~n s &he produc tlon of f~p'i rnachin~ry And f~~iy~ they ha~v~e entered tite rituiti im~rket with a~øally unusual 1 OOOc~ Three

ta _ThL! lpte~ of tering is a. naqtw aluminum four stroke with a %nj~tti~rrs~ doubjc ovSread cam design Un1dç~ othet Threes on the niarlcet ttte.~flverda's crankpifi~< are assembled I 80 degrees A&j~)I-tt phase to i~rie another I~ othet o*ds ts'The two oUtstdSyibt otis are at `k~p dead cqflferiTDC) tht Tenter ou~ is ati,ottom deal jj1er (I3DC~ Thts in tt~e1t gives the Tluee sound binniar to-that oj i/our wjth one wire dssoonne~,.tëd particularly $ lqw eugmopeeds

it s odd soundIng (cit sure and th*t1s exactly why we billed it as a three cylinder ronr There is rgally~no way frmake the unit mellow *1~iJa,tkjnkrth,e Trident but the standard pipe a$ muffler arransentcnt do tend to aggravate the sound Tins system consists 61 tl%ree header p~jthat merge into a single collectoi 4uãttIen sptxt jCrnT&twoi mufflers Fort unawly thw is n optional collector systeiff~that sh~.ild help thc sojnj. a bit, as well as irr1~rae appearance and pertormanee Q~ui only ht1j~e is jjigI co4Ctor is as quiet as 1J!eø@a~dard exhaust -

Ilie sound Z~y~turn sotnc~way, bitt those Who ride the ÍOOO for a time tend to forget about it because their thoughts eventually turn to vibration, or, in this case, the lack of it.

It’s really neat to ride a big bore bike that isn’t much bothered with the annoyances of vibration. The Laverda^^’t bothered at all. The crank arrangement takes care of That problem, eliminating the need for contrarotating weights, as well. A slight lope at idle and slow speeds, kind of like a Norton’s, is the only indication you have that the engine is running at all.

Laverda took time when they developed the 1000. It shows when you ride and it shows when you dismantle the engine for a look inside. In a way, the top end of the Three is similar to a Zl’s, since valve adjustment is accomplished by a choice of different thickness spacers placed under the cam lobe. In this instance, shims are placed under a cup that covers the valve and spring. The cup is relieved underneath to accept the shim. Due to the large diameter of the cam drive gears and their close proximity to one another, it’s not necessary, as it is with the Zl, to use an idler gear to keep the cam chain running true.

Gas and air headed for the cylinders is mixed in three 32mm Dell’Orto carburetors. These are designed with accelerator pumps to aid fuel flow and low-speed response. While these units are an improvement over standard square Dell’Ortos, they still have a way to go to equal the performance of a Mikuni.

The biggest disadvantage with them is in the movement of the slide. Travel is excessive, requiring at least two handfuls of throttle before the slides are fully opened. And once the slide is open on a cruise setting, it requires a strong right arm to hold it there. Stuck slides, however, should be impossible with such heavy return springs.

Bosh electrics supply spark for the ignition on the 1000. Instead of points, the Laverda sports a pointless ET (energy transfer) magneto. Spark is there in abundance, even in the worst conditions. This is important, since the Laverda isn’t equipped with a kickstarter lever, not that this is bad, as long as the battery is properly maintained. Besides, the big Three would take a lot of effort to kick through.

The power half of the engine is coupled to the transmission by a triplex chain, due to the space required to house an enormous clutch and electric starter. To allow clearance for these it was impossible to gear drive the transmission, ^^h Laverda’s arrangement, the countershaft sprocket is locate^Pn the mainshaft of the transmission. This is common practice with most bikes using a primary chain.

Inside the transmission, the shifter drum isn’t a drum at all. Instead, it’s a semicircular device that has grooves cut in the top. Three shifter forks ride in the grooves. The rest of the mechanism functions normally. The drum is gear-driven, making the shifts through all five gears positive and effortless.

Because of the smooth power pulses of the Three, Laverda feels that a 5/8 x 3/8 drive chain is sufficient for driving the wheel.

With the exception of cleaning the washable oil filter, servicing should be a snap. Filter removal requires removal of the exhaust pipes. Luckily this isn’t required for every oil change or it would get old real quick.

Frame wise, the tubes that hold the Laverda together, do so satisfactorily. The engine is attached in a conventional double cradle arrangement, amply braced by a sturdy single top tube that is approximately two inches in diameter. Attachment of the steering head post to the frame is well done;^^s triangulated to insure against flex. We only wish that anowrer material besides heavy gauge steel was chosen. Flexing can be kept to a minimum with the use of any material if enough is> used, and weight savings can be considerable. The rest of the unit is just as well supported and is therefore not prone to cause any undue surprises when cornering.

Besides being strong, the Laverda is tucked in well for cornering. Nothing on the frame drags the ground when pushing hard. Even the centerstand is out of the way and easy to use.

Complementing the power and handling are Dunlop 4.10-18 tires that, in traction and profile, are the closest thing to road racing skins we have seen for street use. Even with the good traction, you can expect 8-10,000 miles before replacement is necessary.

Slow-speed handling is somewhat sluggish. We attribute this to the preload put on the taper bearings in the steering head. Once above 10-15 mph, this sensation disappears. At speed, the front end holds the road well and has no tendency to wander, even when pavement is rough.

As is to be expected, suspension components are a bit on the firm side. This is one clue to the intended use of this sportster. Both spring rate and damping are well-suite^^ the cafe type of riding. Any length of time in a straight line causes some discomfort to the tailbone, but what doesn’t short of a Harley 74?

The rear dampers are adjustable to five different preload positions. This range of adjustment was satisfactory for all the conditions we encountered.

One important aspect of performance is deceleration, and when it becomes necessary to stop, the Laverda can do it with the best of them. At the rear is a huge drum with a diameter of 9.05 in. and a shoe width of 1.18 in. Add to these dimensions the fact that it’s a double leading shoe stopper, and you have brake that is as large or larger than front brakes fitted to some road bikes. Because of the size, we feel this brake is on the verge of being overly sensitive. Really, a road racer couldn’t ask for more.

Early Threes came with a two-panel, double leading shoe front brake. It had the same dimensions as the rear, except that there were two of them. Needless to say, there was just as much or more brake than traction.

Now, Laverda Threes come with a dual disc set-up is, believe it or not, better than the drum predecessor. Slightly more lever pressure than expected is required to slow the big bike, but once applied, stopping is rapid, without any fade at all.

The old world craftsmanship that we talked about earlier is still evident on the Laverda. The only thing we could point a disapproving finger at was the orange peel texture of the paint on the large five-gallon fuel tank.

Welds are nearly perfect. They look as though they were done by a custom frame builder and they probably were. Castings are a little rough for some peoples tastes, but we found their appearance to our liking.

Both the tachometer and speedometer are of Japanese manufacture, made by none other than ND, the firm that creates instruments for Honda, among others.

Handlebars are really unique. They not only swivel in their mounts atop the triple clamp, but also have an additional pivot point near the top of their rise on each side. By fiddling with these three points, anyone can come up with a configi^Bfcion with the right feel for him.

As a final touch, the 18-in. alloy rims are polished, as is the center portion of the rear hub. Fenders are simple in shape and are chromed in the classic roadster tradition.

At 500 lb., the Laverda is a tad overweight, but the power is there to pull it and it is one of the smoothest roadsters on. the highway. Handling is there too and, as a bonus, nothing drags through the turns.

The Laverda 1000, then, is quite a bike...a bike that is able to keep pace in a field that is literally improving by leaps and bounds.

Unfortunately, this effort by Laverda will, for the most part, go unnoticed by the majority of the motorcycling public. For one thing, Japanese multis dominate the showrooms in every city, in every state. Laverdas are very rare indeed. Japanese multis are built within a cost range and are priced to move quickly. Laverdas are built to last and are priced accordingly (price in the U.S. is estimated at $3400). So Laverda cannot compete in the marketplace. Period.

The Laverda lOOOcc Three, then, is a machine ftAhe connoisseur, not the masses! It’s a machine for the mai^vho not only can afford to own something unique, but who demands it.

LAVERDA 1000

$3400