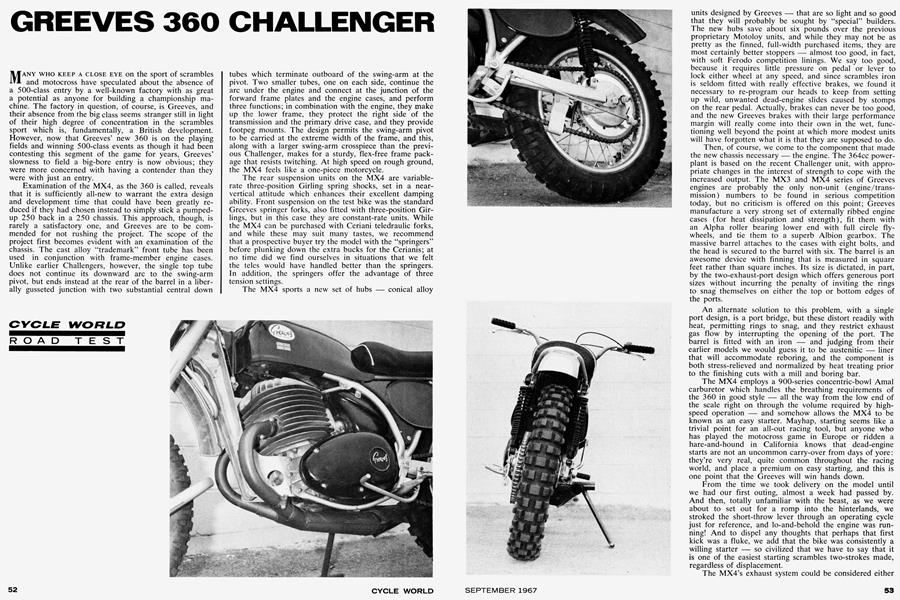

GREEVES 360 CHALLENGER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

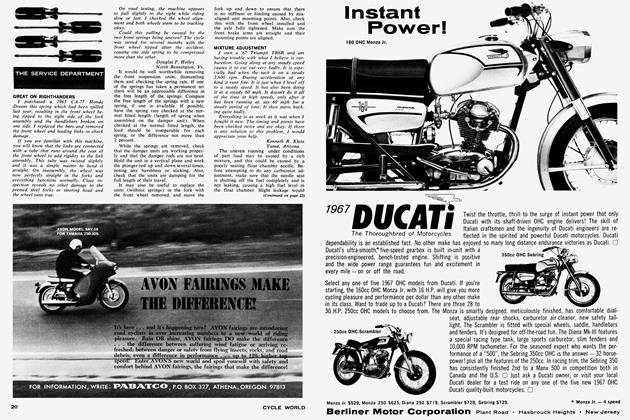

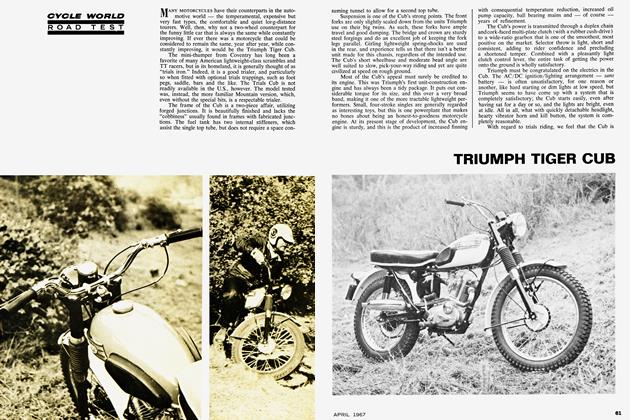

MANY WHO KEEP A CLOSE EYE on the sport of scrambles and motocross have speculated about the absence of a 500-class entry by a well-known factory with as great a potential as anyone for building a championship machine. The factory in question, of course, is Greeves, and their absence from the big class seems stranger still in light of their high degree of concentration in the scrambles sport which is, fundamentally, a British development. However, now that Greeves' new 360 is on the playing fields and winning 500-class events as though it had been contesting this segment of the game for years, Greeves' slowness to field a big-bore entry is now obvious; they were more concerned with having a contender than they were with just an entry.

Examination of the MX4, as the 360 is called, reveals that it is sufficiently all-new to warrant the extra design and development time that could have been greatly reduced if they had chosen instead to simply stick a pumpedup 250 back in a 250 chassis. This approach, though, is rarely a satisfactory one, and Greeves are to be commended for not rushing the project. The scope of the project first becomes evident with an examination of the chassis. The cast alloy "trademark1' front tube has been used in conjunction with frame-member engine cases. Unlike earlier Challengers, however, the single top tube does not continue its downward arc to the swing-arm pivot, but ends instead at the rear of the barrel in a liberally gusseted junction with two substantial central down tubes which terminate outboard of the swing-arm at the pivot. Two smaller tubes, one on each side, continue the arc under the engine and connect at the junction of the forward frame plates and the engine cases, and perform three functions; in combination with the engine, they make up the lower frame, they protect the right side of the transmission and the primary drive case, and they provide footpeg mounts. The design permits the swing-arm pivot to be carried at the extreme width of the frame, and this, along with a larger swing-arm crosspiece than the previous Challenger, makes for a sturdy, flex-free frame package that resists twitching. At high speed on rough ground, the MX4 feels like a one-piece motorcycle.

The rear suspension units on the MX4 are variablerate three-position Girling spring shocks, set in a nearvertical attitude which enhances their excellent damping ability. Front suspension on the test bike was the standard Greeves springer forks, also fitted with three-position Girlings, but in this case they are constant-rate units. While the MX4 can be purchased with Ceriani teledraulic forks, and while these may suit many tastes, we recommend that a prospective buyer try the model with the "springers" before plunking down the extra bucks for the Cerianis; at no time did we find ourselves in situations that we felt the teles would have handled better than the springers. In addition, the springers offer the advantage of three tension settings.

The MX4 sports a new set of hubs — conical alloy units designed by Greeves — that are so light and so good that they will probably be sought by "special" builders. The new hubs save about six pounds over the previous proprietary Motoloy units, and while they may not be as pretty as the finned, full-width purchased items, they are most certainly better stoppers — almost too good, in fact, with soft Ferodo competition linings. We say too good, because it requires little pressure on pedal or lever to lock either wheel at any speed, and since scrambles iron is seldom fitted with really effective brakes, we found it necessary to re-program our heads to keep from setting up wild, unwanted dead-engine slides caused by stomps on the rear pedal. Actually, brakes can never be too good, and the new Greeves brakes with their large performance margin will really come into their own in the wet, functioning well beyond the point at which more modest units will have forgotten what it is that they are supposed to do.

Then, of course, we come to the component that made the new chassis necessary — the engine. The 364cc powerplant is based on the recent Challenger unit, with appropriate changes in the interest of strength to cope with the increased output. The MX3 and MX4 series of Greeves engines are probably the only non-unit (engine/transmission) numbers to be found in serious competition today, but no criticism is offered on this point; Greeves manufacture a very strong set of externally ribbed engine cases (for heat dissipation and strength), fit them with an Alpha roller bearing lower end with full circle flywheels, and tie them to a superb Albion gearbox. The massive barrel attaches to the cases with eight bolts, and the head is secured to the barrel with six. The barrel is an awesome device with finning that is measured in square feet rather than square inches. Its size is dictated, in part, by the two-exhaust-port design which offers generous port sizes without incurring the penalty of inviting the rings to snag themselves on either the top or bottom edges of the ports.

An alternate solution to this problem, with a single port design, is a port bridge, but these distort readily with heat, permitting rings to snag, and they restrict exhaust gas flow by interrupting the opening of the port. The barrel is fitted with an iron — and judging from their earlier models we would guess it to be austenitic — liner that will accommodate reboring, and the component is both stress-relieved and normalized by heat treating prior to the finishing cuts with a mill and boring bar.

The MX4 employs a 900-series concentric-bowl Amal carburetor which handles the breathing requirements of the 360 in good style — all the way from the low end of the scale right on through the volume required by highspeed operation — and somehow allows the MX4 to be known as an easy starter. Mayhap, starting seems like a trivial point for an all-out racing tool, but anyone who has played the motocross game in Europe or ridden a hare-and-hound in California knows that dead-engine starts are not an uncommon carry-over from days of yore: they're very real, quite common throughout the racing world, and place a premium on easy starting, and this is one point that the Greeves will win hands down.

From the time we took delivery on the model until we had our first outing, almost a week had passed by. And then, totally unfamiliar with the beast, as we were about to set out for a romp into the hinterlands, we stroked the short-throw lever through an operating cycle just for reference, and lo-and-behold the engine was running! And to dispel any thoughts that perhaps that first kick was a fluke, we add that the bike was consistently a willing starter — so civilized that we have to say that it is one of the easiest starting scrambles two-strokes made, regardless of displacement.

The MX4's exhaust system could be considered either a marvel or a nightmare, depending on one's turn of mind. On the one hand, it must be considered a marvel because the lone expansion chamber must chore for two rather sizable exhaust pipes, from one rather sizable cylinder, without weighing 11-hundred pounds and being the second-largest component on the bike. On these points it does well. However, its placement, dictated by necessity, makes it a rather vulnerable hunk of hardware. The problem here has become a classic one; if you want to breathe well, you've got to have a big nose. And, if you want to be a fighter, you're going to have that big nose broken every so often. Curiously, the only component on the MX4 that is subject to any manner of physical harassment is the exhaust pipe, but the problem seems to have been solved by one Greeves-phile — a light equipment manufacturer — who has constructed a very neat protective boot for the 360's exhaust system. Our test bike was fitted with one of these items, and when we asked Greeves distributor Nick Nicholson about it, he replied that he felt that it was an essential mod for American racing and would see that the guards were available at a reasonable cost to anyone purchasing a 360.

For ignition, Greeves return to their old standby — for the Challenger series — Stefa. And as they have done in the recent past, they have mounted the efficient, selfcontained unit on the crankshaft behind a water-tight cover that is in turn protected by an outer cap.

The control layout on the MX4 is quite good, to the point of being considered excellent. Peg placement accommodates the standing position with a great deal of comfort, and the very ample saddle — found only on the U. S. models, and thanks to Nick Nicholson — makes sitting down a most pleasant attitude. The foot pegs, incidentally, will be of the folding variety for all of the units sold in this country, despite the fact that our test bike — the first MX4 into the country — did not have them. Little niceties include a light clutch control, a nylon throttle and a gear selector that requires little pressure,

has short travel, and can be criticized only in that it is a bit distant from the foot peg and thus requires that the boot be lifted from the peg to engage the selector. The MX4's handlebars are made of near-unbendable one-inchdiameter tempered spring steel tubing that is swaged down to 7/8-inch on the ends to accommodate readily available control levers and grips.

In addition to having a more amply padded saddle, the stateside version of the MX4 also has a larger fuel tank than its domestic counterpart — 2.4 versus 1.75 gallons — welcome news to those considering the bike for long-distance events. The quality of construction and finish on the fuel tank, and the enormous still-air box which houses two generous Fram-type air cleaners covered by the integral side number plates, is extremely good; but this is no surprise when one considers that Greeves have been working with fiberglass for some time in their Invacar division.

As we've said, the MX4 is a willing starter. But, it is an even more willing worker. The torque band is uncommonly wide, more akin to a spirited big-bore, four-stroke single than a highly tuned two-stroke. The almost complete absence of pipiness is surprising for an engine that pulls as hard as this one does; thus it is that the wick can be turned up early, and hard, in bumpy turns without risk of looping or control loss when the engine hits its stride. It is always on stride, from the low end of the register up to peak revs.

The wondrous torque characteristics of the MX4 complement the rock-steady handling of this truly fine, wellbalanced piece of racing hardware, and these, in combination with first-class welding and fabrication, the exclusive use of self-locking nuts, heavy-duty bits in vulnerable spots, a competitive price and readily available racing spares, add up to one of the strongest 500-class contenders ever to circuit a scrambles track or sprint across the desert. And that's why it has taken a little time in coming to us. ■

GREEVES

CHALLENGER 360cc