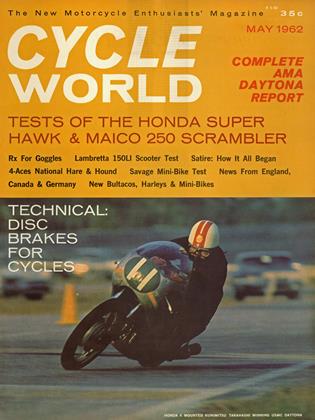

MAICO 250 SCRAMBLER

Cycle World Road Test

NOWHERE is the two-stroke engine more popular or more highly developed than in Germany, where the two-stroke operating cycle was invented. German airplanes, boats, automobiles, power-stations and, of course, motorcycles have - as so often as not - twostroke engines. In fact, Germany is one of the few places where the "popcorn-poppers" have been developed sufficiently to offer such a wide-range challenge to the four-stroke cycle engine. Elsewhere, the two-stroke is used only when its main advantages - simplicity, light weight - overcome such disadvantages as part-throttle roughness and uncertain fuel economy. However, this may be due to the world's inexperience with the type the Germans have demonstrated (as have certain companies in other countries) that the two-stroke engine can be a very satisfactory prime-mover indeed.

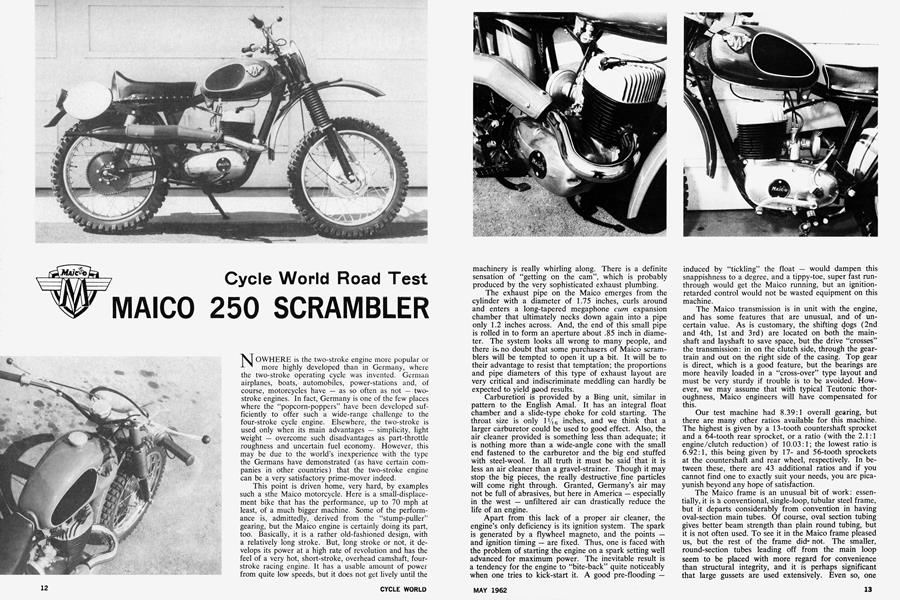

This poiht is driven~home, very hard, by examples such a sthe Maico motorcycle. Here is a small-displace ment bike that has the performance, up to 70 mph at least, of a much bigger machine. Some of the perform ance is, admittedly, derived from the "stump-puller" gearing, but the Maico engine is certainly doing its part, too. Basically, it is a rather old-fashioned design, with a relatively long stroke. But, long stroke or not, it de velops its power at a high rate of revolution and has the feel of a very hot, short-stroke, overhead camshaft, four stroke racing engine. It has a usable amount of power from quite low speeds, but it does not get lively until the machinery is really whirling along. There is a definite sensation of “getting on the cam”, which is probably produced by the very sophisticated exhaust plumbing.

The exhaust pipe on the Maico emerges from the cylinder with a diameter of 1.75 inches, curls around and enters a long-tapered megaphone cum expansion chamber that ultimately necks down again into a pipe only 1.2 inches across. And, the end of this small pipe is rolled in to form an aperture about .$5 inch in diameter. The system looks all wrong to many people, and there is. no doubt that some purchasers of Maico scramblers will be tempted to open it up a bit. It will be to their advantage to resist that temptation; the proportions and pipe diameters of this type of exhaust layout are very critical and indiscriminate meddling can hardly be expected to yield good results.

Carburetiori is provided by a Bing unit, similar in pattern to the English Amal. It has an integral float chamber and a slide-type choke for cold starting. The throat size is only l1/^ inches, and we think that a larger carburetor could be used to good effect. Also, the air cleaner provided is something less than adequate; it is nothing more than a wide-angle cone with the small end fastened to the carburetor and the big end stuffed with steel-wool. In all truth it must be said that it is less an air cleaner than a gravel-strainer. Though it may stop the big pieces, the really destructive, fine particles will come right through. Granted, Germany’s air may not be full of abrasives, but here in America — especially in the west — unfiltered air can drastically reduce the life of an engine.

Apart from this lack of a proper air cleaner, the engine’s only deficiency is its ignition system. The spark is generated by a flywheel magneto, and the points — and ignition timing — are fixed. Thus, one is faced with the problem of starting the engine on a spark setting well advanced for maximum power. The inevitable result is a tendency for the engine to “bite-back” quite noticeably when one tries to kick-start it. A good pre-flooding —

induced by “tickling” the float — would dampen this snappishness to a degree, and a tippy-toe, super fast runthrough would get the Maico running, but an ignitionretarded control would not be wasted equipment on this machine.

The Maico transmission is in unit with the engine, and has some features that are unusual, and of uncertain value. As is customary, the shifting dogs (2nd and 4th, 1st and 3rd) are located on both the mainshaft and layshaft to save space, but the drive “crosses” the transmission: in on the clutch side, through the geartrain and out on the right side of the casing. Top gear is direct, which is a good feature, but the bearings are more heavily loaded in a “cross-over” type layout and must be very sturdy if trouble is to be avoided. However, we may assume that with typical Teutonic thoroughness, Maico engineers will have compensated for this.

Our test machine had 8.39:1 overall gearing, but there are many other ratios available for this machine. The highest is given by a 13-tooth countershaft sprocket and a 64-tooth rear sprocket, or a ratio (with the 2.1:1 engine/clutch reduction) of 10.03:1; the lowest ratio is 6.92:1, this being given by 17and 56-tooth sprockets at the countershaft and rear wheel, respectively. In between these, there are 43 additional ratios and if you cannot find one to exactly suit your needs, you are picayunish beyond any hope of satisfaction.

The Maico frame is an unusual bit of work: essentially, it is a conventional, single-loop, tubular steel frame, but it departs considerably from convention in having oval-section main tubes. Of course, oval section tubing gives better beam strength than plain round tubing, but it is not often used. To see it in the Maico frame pleased us, but the rest of the frame did* not. The smaller, round-section tubes leading off from the main loop seem to be placed with more regard for convenience than structural integrity, and it is perhaps significant that large gussets are used extensively. Even so, one cannot ignore the fact that, regardless of our opinions, the frame seems to be sufficiently strong even for the immense stresses encountered in scrambles work. Moreover, despite the fact that the Maico is fashioned almost entirely of steel or iron (this includes the fuel tank, fenders and the fender braces — and even the numberplates are of steel) the complete machine, ready to run, weighs only 9 pounds more than another 250cc-engined scrambler that is made almost entirely of light aluminum alloys.

The suspension, telescopic forks front, swing-arms rear, is characterized by a large amount of wheel travel available, and by the steep angle of the forks. Apparently, the fork angle is set to give good steering even when axle-deep in sand and they do the job at low speeds.

Whatever the individual rider may think of the Maico’s handling — and on our own staff we got a wide spread of opinion — it cannot be denied that it has a thing or two in its favor. There is a steering damper that gives smooth, smooth action and effectively cancels a tendency (shared by all too many bikes) for the front wheel to flap violently from lock to lock at high speeds over rough terrain. Also, the long suspension travel takes up as much of the shock of running across the badlands as can reasonably be expected.

The brakes, on which we were able to obtain little information as to lining area, -etc., gave good stopping without very much force required, and were generally more than adequate for a scrambles machine.

Saddle, fuel-tank, handlebars, foot-pegs and controls were all disposed in a manner that gave a maximum of comfort and controllability. Both foot-pegs and the saddle had turned-up ends, to give secure footing and whatever-you-wish-to-term-it. Knee-notches are formed in the tank for anyone whose knees fit there — ours were only a near-miss, and the wide, flat bars give just the kind of leverage one needs to cope with those vertical forks.

The finish varied considerably from point to point on the Maico. The engine appeared to be a fine piece of work, with as clean a bit of casting work on the cylinder as one might ever hope to see, and buffed aluminum much in evidence down on the crank/transmission casing. The fenders, which do not bounce with the wheels (a superior arrangement) are neatly formed and mounted, as is the fuel tank, and the black-and-red paint looked high in both gloss and quality. However, the suspension parts and frame — although sturdy enough — were not up to the same standard. The black enamel on the frame tubes appeared in spots to have been applied with the proverbial “sandy broom.” Further, the welding was untidy (though we cannot say that it looked fragile) and the bare, sawed-off end of one main tube was left open and exposed. These are little things, but they do detract greatly from a machine that has a lot, in the main, to offer.

While we were irritated by the Maico’s flaws, it nonetheless left us impressed. Some of the flat-out handling traits were not pleasing to some members of our staff, but it was conceded by all that at a pace just off of the maximum, the Maico is stable and pleasant — a good bike for the rider who is a novice in the dirt but not entirely new to motorcycles. •

MAICO

250 SCRAMBLER

$675.00

SPECI FICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

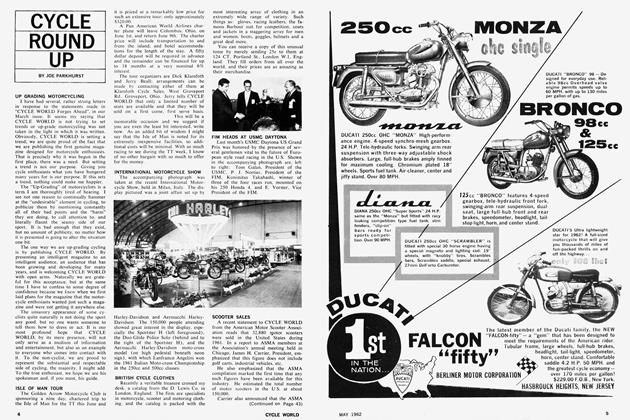

Cycle Round Up

May 1962 By Joe Parkhurst -

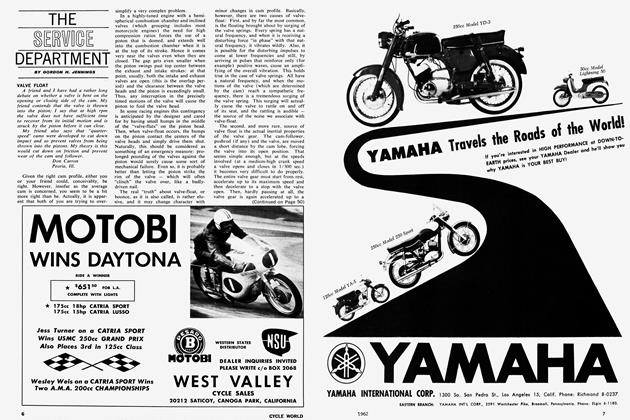

The Service Department

The Service DepartmentValve Float

May 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

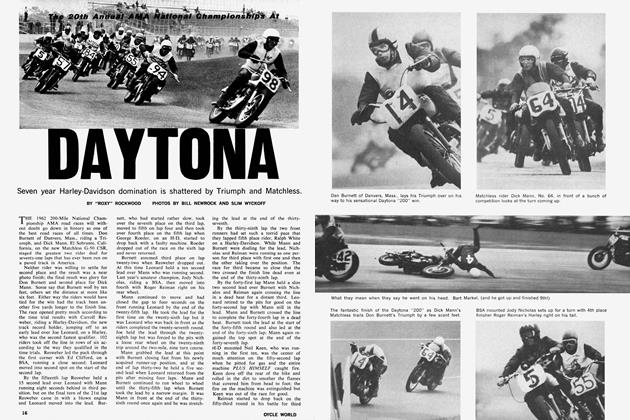

Daytona

May 1962 By "Roxy" Rockwood -

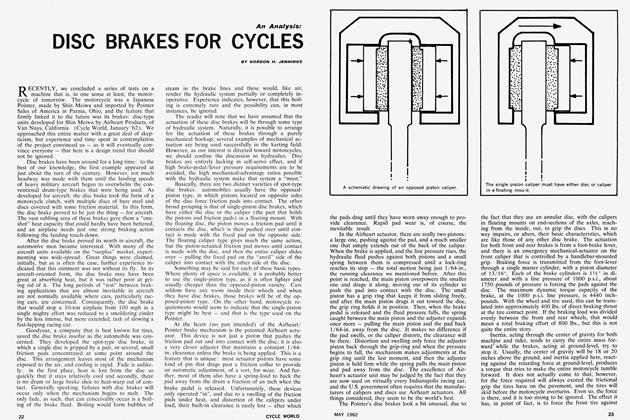

An Analysis

An AnalysisDisc Brakes For Cycles

May 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

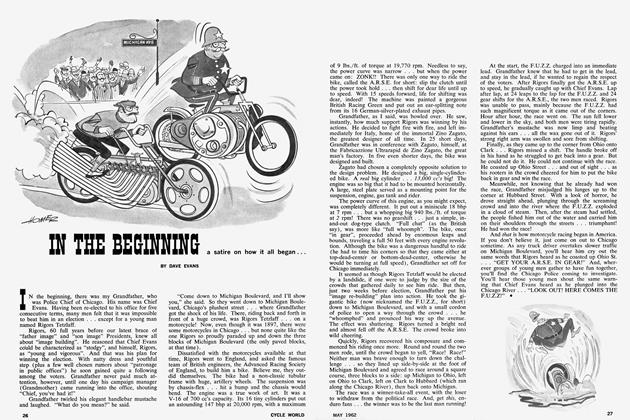

Satire

SatireIn the Beginning

May 1962 By Dave Evans -

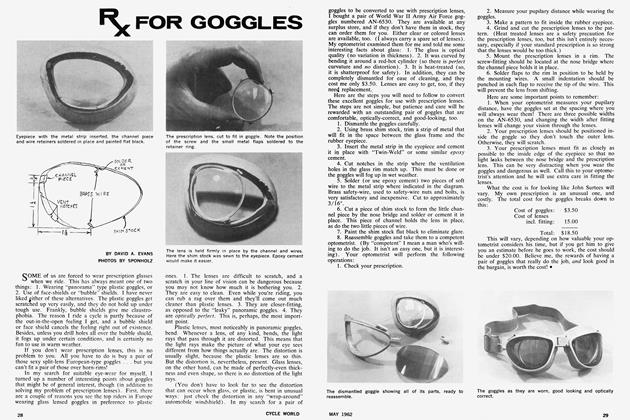

Scooter Test

Scooter TestRx For Goggles

May 1962 By David A. Evans