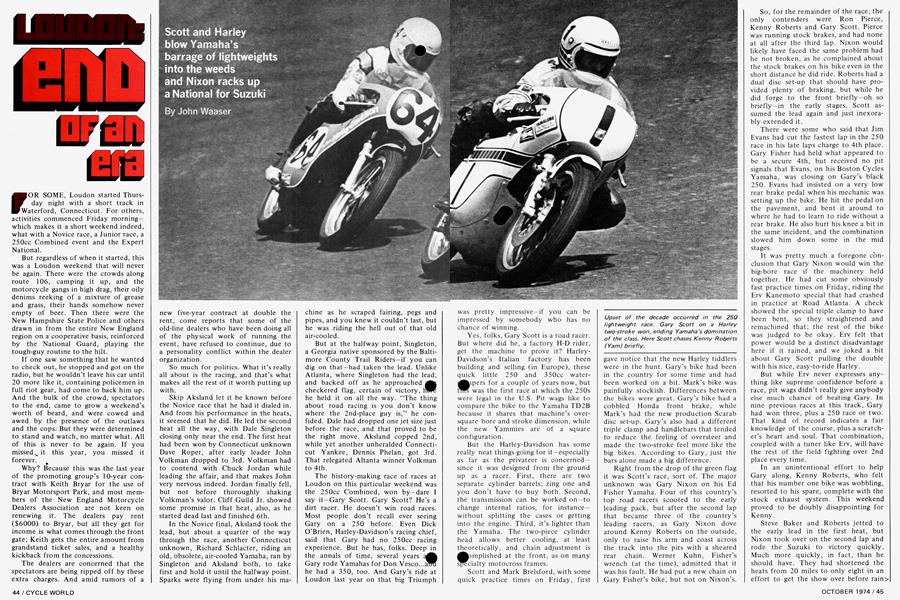

LOUDON: END OF AN ERA

Scott and Harley blow Yamaha's barrage of lightweights into the weeds and Nixon racks up a National for Suzuki

John Waaser

FOR SOME, Loudon started Thursday night with a short track in Waterford, Connecticut. For others, activities commenced Friday morning— which makes it a short weekend indeed, what with a Novice race, a Junior race, a 250cc Combined event and the Expert National.

But regardless of when it started, this was a Loudon weekend that will never be again. There were the crowds along route 106, camping it up, and the motorcycle gangs in high drag, their oily denims reeking of a mixture of grease and grass, their hands somehow never empty of beer. Then there were the New Hampshire State Police and others drawn in from the entire New England region on a cooperative basis, reinforced by the National Guard, playing the tough-guy routine to the hilt.

If one saw something that he wanted to check out, he stopped and got on the radio, but he wouldn’t leave his car until 20 more like it, containing policemen in full riot gear, had come to back him up. And the bulk of the crowd, spectators to the end, came to grow a weekend’s worth of beard, and were cowed and awed by the presence of the outlaws and the cops: But they were determined to stand and watch, no matter what. All of this is never to be again. If you missed.^ it this year, you missed it forever.

Why? Because this was the last year of the promoting group’s 10-year contract with Keith Bryar for the use of Bryar Motorsport Park, and most members of the New England Motorcycle Dealers Association are not keen on renewing it. The dealers pay rent ($6000) to Bryar, but all they get for income is what comes through the front gate; Keith gets the entire amount from grandstand ticket sales, and a healthy kickback from the concessions.

The dealers are concerned that the spectators are being ripped off by these extra charges. And amid rumors of a new five-year contract at double the rent, come reports that some of the old-line dealers who have been doing all of the physical work of running the event, have refused to continue, due to a personality conflict within the dealer organization.

So much for politics. What it’s really all about is the racing, and that’s what makes all the rest of it worth putting up with.

Skip Aksland let it be known before the Novice race that he had it dialed in. And from his performance in the heats, it seemed that he did. He led the second heat all the way, with Dale Singleton closing only near the end. The first heat had been won by-Connecticut unknown Dave Roper, after early leader John Volkman dropped to 3rd. Volkman had to contend with Chuck Jordan while leading the affair, and that makes John very nervous indeed. Jordan finally fell, but not before thoroughly shaking Volkman’s valor. Cliff Guild Jr. showed some promise in that heat, also, as he started dead last and finished 6th.

In the Novice final, Aksland took the lead, but about a quarter of the way through the race, another Connecticut unknown, Richard Schlacter, riding an old, obsolete, air-cooled Yamaha, ran by Singleton and Aksland both, to take first and hold it until the halfway point. Sparks were flying from under his machine as he scraped fairing, pegs and pipes, and you knew it couldn’t last, but he was riding the hell out of that old air-cooled.

But at the halfway point, Singleton, a Georgia native sponsored by the Baltimore County Trail Riders—if you can dig on that —had taken the lead. Unlike Atlanta, where Singleton had the lead, and backed off as he approached checkered flag, certain of victory, IwK he held it on all the way. “The thing about road racing is you don’t know where the 2nd-place guy is,” he confided. Dale had dropped one jet size just before the race, and that proved to be the right move. Aksland copped 2nd, while yet another unheralded Connecticut Yankee, Dennis Phelan, got 3rd. That relegated Altanta winner Volkman to 4th.

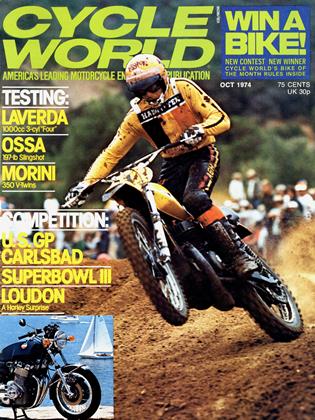

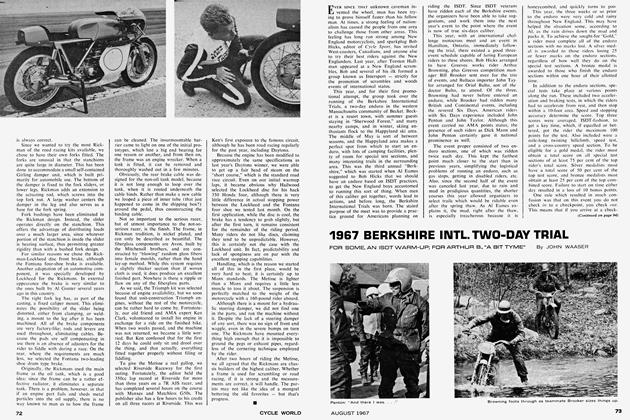

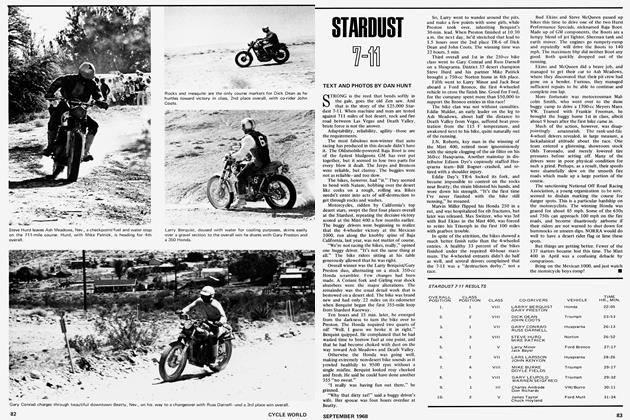

The history-making race of races at Loudon on this particular weekend was the 250cc Combined, won by—dare I say it—Gary Scott. Gary Scott? He’s a dirt racer. He doesn’t win road races. Most people don’t recall ever seeing Gary on a 250 before. Even Dick O’Brien, Harley-Davidson’s racing chief, said that Gary had no 250cc racing experience. But he has, folks. Deep in the annals of time, several years Gary rode Yamahas for Don Vesco...^W he had a 350, too. And Gary’s ride at Loudon last year on that big Triumph was pretty impressive—if you can be impressed by somebody who has no chance of winning.

Yes, folks, Gary Scott is a road racer. But where did he, a factory H-D rider, get the machine to prove it? HarleyDavidson’s Italian factory has been building and selling (in Europe), these quick little 250 and 350cc waterï^^ipers for a couple of years now, but was the first race at which the 250s were legal in the U.S. Pit wags like to compare the bike to the Yamaha TD2B because it shares that machine’s oversquare bore and stroke dimension, while the new Yammies are of a square configuration.

But the Harley-Davidson has some really neat things going for it —especially as far as the privateer is concerned— since it was designed from the ground up as a racer. First, there are two separate cylinder barrels; zing one and you don’t have to buy both. Second, the transmission can be worked on—to change internal ratios, for instance — without splitting the cases or getting into the engine. Third, it’s lighter than the Yamaha. The two-piece cylinder head allows better cooling, at least theoretically, and chain adjustment is

»mplished at the front, as on many ialty motocross frames.

Scott and Mark Brelsford, with some quick practice times on Friday, first gave notice that the new Harley tiddlers were in the hunt. Gary’s bike had been in the country for some time and had been worked on a bit. Mark’s bike was painfully stockish. Differences between the bikes were great. Gary’s bike had a cobbled Honda front brake, while Mark’s had the new production Scarab disc set-up. Gary’s also had a different triple clamp and handlebars that tended to reduce the feeling of oversteer and made the two-stroke feel more like the big bikes. According to Gary, just the bars alone made a big difference.

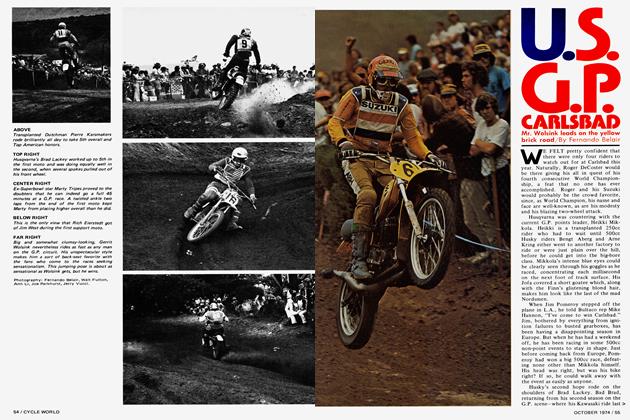

Right from the drop of the green flag it was Scott’s race, sort of. The major unknown was Gary Nixon on his Ed Fisher Yamaha. Four of this country’s top road racers scooted to the early leading pack, but after the second lap that became three of the country’s leading racers, as Gary Nixon dove around Kenny Roberts on the outside, only to raise his arm and coast across the track into the pits with a sheared rear chain. Werner Kuhn, Fisher’s wrench (at the time), admitted that it was his fault. He had put a new chain on Gary Fisher’s bike, but not on Nixon’s. So, for the remainder of the race, the only contenders were Ron Pierce, Kenny Roberts and Gary Scott. Pierce was running stock brakes, and had none at all after the third lap. Nixon would likely have faced the same problem had he not broken, as he complained about the stock brakes on his bike even in the short distance he did ride. Roberts had a dual disc set-up that should have provided plenty of braking, but while he did forge to the front briefly—oh so briefly—in the early stages, Scott assumed the lead again and just inexorably extended it.

There were some who said that Jim Evans had cut the fastest lap in the 250 race in his late laps charge to 4th place. Gary Fisher had held what appeared to be a secure 4th, but received no pit signals that Evans, on his Boston Cycles Yamaha, was closing on Gary’s black 250. Evans had insisted on a very low rear brake pedal when his mechanic was setting up the bike. He hit the pedal on the pavement, and bent it around to where he had to learn to ride without a rear brake. He also hurt his knee a bit in the same incident, and the combination slowed him down some in the mid stages.

It was pretty much a foregone conclusion that Gary Nixon would win the big-bore race if the machinery held together. He had cut some obviously fast practice times on Friday, riding the Erv Kanemoto special that had crashed in practice at Road Atlanta. A check showed the special triple clamp to have been bent, so they straightened and remachined that; the rest of the bike was judged to be okay. Erv felt that power would be a distinct disadvantage here if it rained, and we joked a bit about Gary Scott pulling the double with his nice, easy-to-ride Harley.

But while Erv never expresses anything like supreme confidence before a race, pit wags didn’t really give anybody else much chance of beating Gary. In nine previous races at this track, Gary had won three, plus a 250 race or two. That kind of record indicates a fair knowledge of the course, plus a scratcher’s heart and soul. That combination, coupled with a tuner like Erv, will have the rest of the field fighting over 2nd place every time.

In an unintentional effort to help Gary along, Kenny Roberts, who felt that his number one bike was wobbling, resorted to his spare, complete with the stock exhaust system. This weekend proved to be doubly disappointing for Kenny.

Steve Baker and Roberts jetted to the early lead in the first heat, but Nixon took over on the second lap and rode the Suzuki to victory quickly. Much more quickly, in fact, than he should have. They had shortened the heats from 20 miles to only eight in an effort to get the show over before rain> set in. This would prove significant later (due to the 60 percent completion rule).

Romero took the early lead in the second heat, but Hurley Wilvert latched onto his Kawasaki’s throttle in a death grip, and took over to win. Jim Evans grabbed 2nd and Steve McLaughlin 3rd, as Romero dropped to 4th.

In the hunt was Cliff Carr, but cresting the back hill he reached up to grab a tear-off face shield, and with one hand on the bars when the front end got light, he became confused and grabbed the front brake, which naturally locked up when the front wheel regained traction. Instant endo the hard way.

The Expert semi was eliminated to save time. Junior heats, however, were held to give the Experts time to prepare for the biggy. Pat Hennen led the early heat at first, with Pee Wee Gleason 2nd. Gleason was riding his 250cc machine with the 350cc barrels and pipes. He didn’t have the 350cc internal gearing, but presumably was able to compensate with secondary gearing.

Atlanta winner Larry Bleil passed Pee Wee, but Hennen was running a new tubeless tire, and pulled into the pit, thinking it had gone flat. Since it was only soft on the bottom, he came back out immediately, looking to scuff the tire in at lower speeds. His sponsor later said it wasn’t even soft. That left Bleil an easy win. Gleason, on the little bike, ran the heat faster than the second heat winner. That put him second on the front row.

Wes Cooley won the second heat, Randy Cleek was 2nd and—you won’t believe this—Justus Taylor 3rd, on an unfaired BMW. Make that a close 3rd. Taylor had crashed his 250 rather violently and rode it on Saturday without a fairing after hasty repairs were made.

Next they gridded the Experts, allowing them to take a warm-up lap for their tires if they so desired. They would regrid and start a three-minute countdown after the warm-up lap. Phil McDonald was in trouble, leaking what appeared to be gasoline onto the track. Kurt Liebmann spotted it and pointed it out to the officials. It turned out to be water from a leaky hose. He was pulled off.

Hurley Wilvert’s bike quit on the line and wouldn’t restart. He was pulled off, too, with whàt turned out to be a major problem in the center cylinder. Kawasaki’s best placer in the heats was out of the final before it started.

The flag dropped and the famous red Yamaha of Whooo? Steve Baker in the lead? That skinny little U.S. citizen who rides for the Canadian factory team? Man, he jetted to the lead from the second row as though he owned it. He’s been around for a long while, and the stories of his getting in somebody’s way haven’t been heard of late, but who would expect him to rocket away from Roberts and Nixon, like that? Going very slowly off the line was Yvon DuHamel. Because of rain, the event was red-flagged on the first lap.

Everybody I talked to felt that the race should have been continued, except, of course, the officials. Two riders gained substantially from the re^Ät. Yvon DuHamel’s mechanic discoveer a stuck float and fixed it, while Phil McDonald replaced his water hose.

Off the line and around the first lap, it was Baker, Roberts, Nixon, McLaughlin, Romero, Aldana, Evans and Gary Scott. DuHamel moved up among the leaders on the second lap, and the third lap set the stage for the quote of the weekend. By this time it was Roberts, followed by a tight dice between Romero and Nixon, then Aldana, Baker, DuHamel, Evans, Scott, McLaughlin, Mike Clarke, Pierce, Smart and Long together, then Baumann and Fisher together, then Billy Labrie and a whole slew of others too close together to identify.

On the fourth lap, DuHamel made a move to get by Steve Baker in the last turn. What he did was to dive inside and tap Steve, like Scott had done tq^k> many riders in the 250 race. Only Yron did it harder and Steve went down. When someone asked him later just how he'd managed to get off, Steve quickly rejoined, "I slipped on a frog."

Meanwhile, on the fifth lap, Romero had taken the lead from his teammate. A lap later, Nixon, too, had passed Roberts and, by the seventh lap, DuHamel had gotten by the champ, who was in serious danger of losing even 4th spot to that famous Mexican jump ing bean, Dave Aldana. By lap 10 Nixon had passed Romero and the top five slots-Nixon, Romero, DuHamel, Rob erts and Aldana-had pulled a large lead on Jim Evans, Gary Scott and Art Baumann.

On the 1 5th lap, Baumann crashed hard at the start line, after grounding the bike and tackling a haybale. Evans sitting in turn two with a massively own gearbox. The ambulance crew came to Baumann's aid, blocking the very fastest line on the front straight, and officials red-flagged the race.

Everybody took advantage of the delay to add gas, install face shield wipers on the backs of their gloves, or do minor repairs. Johnny Long had sucked a base gasket, so the bike "sounded like his old Zundapp." Before they could get the show back on the road, it started raining. Then the fun really started. The race was postponed until 10:30 Monday morning.

Monday's weather was uncertain, but there was little reason to suspect that it would be any better than Sunday's. Mel Dinesen, who pulled the weekend's big boner on Saturday morning by trying to push off the TZ700 with the caps still ` the carbs (they wondered why the r wheel wouldn't turn after a couple of brief reports out of the pipes), had a simple solution. "If it rains, we'll pull the two outside plugs and have a 350 Single." "Torquey mother," intoned his rider, Steve McLaughlin. But most of the guys couldn't find anything to joke about.

Baumann was back at the track Monday morning. "What happened, Art?"

"I got hit with a pile driver last night."

"What kind of damage did you do to yourself?" --

"Just shortened my body .

Actually, he had a bandaged hand and a few stitches, bruises and abrasions from his knee to his shoulder. But after the pain pills wore off, he wasn't in too bad a shape. The appointed hour for the race came and went, with the skies still pouring out liquid sunshine, and no action from the officials.

Finally they called a riders' meeting, specifically excluding members of the press, sponsors and mechanics. When they found it difficult to enforce that order, they moved the meeting inside a nearby refreshment stand and took a roll call, admitting the riders only as their names were called. A few of us found an urgent need to use the mens room in the back of the stand, but the pit steward, who seemed to enjoy play ing the role of enforcer, kicked us out.

What happened was this. The pro moter had refused to pay the purse unless the 60 percent of the race called for in the rule book was completed. Since the "event" in this case would include the heat races, shortening them meant that more of the final would have to be completed. The AMA plan, which Charlie Watson was laying on the riders, involved paying the riders from Sun day's positions, and running another 15 laps to complete the required 60 per cent. It would, in effect, be a parade.

Irrespective of the plan, the AMA has a rule, often used in dirt tracking, that would disqualify Baumann, since he was the cause of the red flag. But the riders got together and decided that Art should get some money out of this. So he showed up on the line on Gary Nixon's 250 Yamaha, wearing Hurley Wilvert's leathers. Roxy Rockwood de scribed the bike as an "official blue and white Kawasaki team entry." This had all the riders chuckling, since the bike was red and white. Many other riders gridded on their spares or their 250s. Afterall, why run the race bike for a slow parade?

In all fairness to the AMA, the problem seemed to hinge on the pro moter's insistence that they run to the letter of their contract and, as Charlie said, it was either this or nothing.

In the afternoon, the sun came out briefly, and the promoter came up to Charlie again, just as Charlie was discuss ing the prospect of holding a race-race with all of the entrants. The promoter wanted them to announce that the Juniors would run, too. Charlie's pa tience had worn thin. The promoter tried to placate Charlie. "I understand, Charlie. I don't want to dictate to you." Funny, that's exactly what he'd been doing all day.

-~ - Charlie still wanted to run the pa rade, since that was what they had decided on. He was ready to do it, simply on the basis of a gentlemens agreement between the 20 top riders. Kenny Roberts felt that they couldn't hold a parade without a written agree ment, signed by everybody, including the 12 riders who would be cut. Charlie looked up at the bright blue sky and said, "But right now, I can't get them to sign." Finally, at 11:45, they decided to restart a race-race at 12:30 from the day before's positions, conditions permit ting. The Junior final would be run afterward. The crowd cheered when informed of this decision. (The "crowd" being a ghost of Sunday's turnout, of course.) They cheered again when in formed that the Juniors would ride.

They held a short practice session and Nixon just couldn't manage to look pumped. The start was to be based on race positions as of a lap before the red flag, not the positions in which they had crossed the line. Due to lapped riders, the two are different. This means that all riders would lose the cushion they had built over the next rider. Riders would be lined up in a staggered forma tion and waved off with one flag, with no time interval. A good drag racing start would gain a rider several positions just on the restart.

(Continued on page 94)

Continued from page 47

Wanna guess who benefited from that one? Steve Baker was gridded 14th, a slot he had worked to following his “frog” incident. With Baumann off, that made him 13th, actually, on the grid. He came around on the first lap after the restart in 6th position. Nixon had the lead, with Roberts 2nd, followed by Romero, Aldana, Pierce, Baker, Scott, Fisher, McLaughlin, Long, DuHamel (who had been gridded 4th), Smart, Phil McDonald and Billy Labrie.

There is probably nobody out there who wishes Scott more luck toward the Championship than Steve McLaughlin, but Steve got by Fisher and started a really super race with Scott for 7th, finally getting by. Pretty soon the front four settled down to Sunday’s order, with Nixon ahead of Romero, Aldana and Roberts, and that’s how they finished. But McLaughlin, DuHamel, Scott and Pierce were involved in a tight scrap for 5th, with Smart and his close follower, Baker, not much behind.

Yvon got by Steve for awhile, but then Steve got it on again, and it looked like he might hold 5th for himself. But on the last lap he hit a bumpy line in the last turn and just had to watch as Yvon pulled out of the turn faster and shot across the line ahead of him.

Nixon popped his usual one-handed wheelie on the parade lap. He certainly deserved the win. Hell, he had to win it twice, just like in the 250cc race last year.

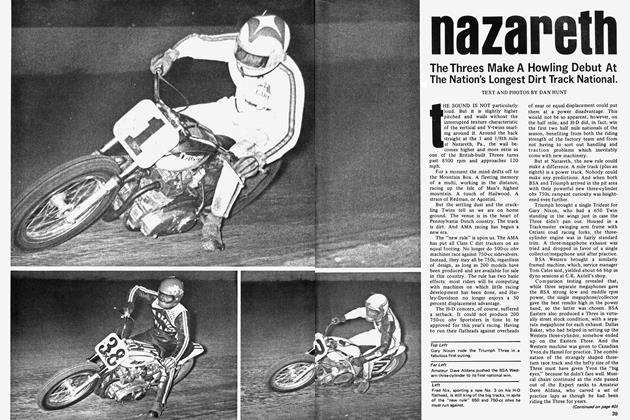

The Juniors got to ride at last. Larry Bleil had the pole and streaked into the lead. But Pee Wee Gleason, who weighs 115 lb., was 3rd into the first turn on his 350 Twin. Pat Hennen, who started 31st, was 3rd at the end of one lap, 2nd at the end of two. By the fourth lap the order had settled down to Bleil, Hennen, Gary Blackman, Randy Cleek, Gleason, Wes Cooley and Justus Taylor on that amazing BMW. Hennen and Bleil were having quite a dice, but by the eighteenth lap or so, Pat had the lead for good, though he never could shake Bleil.

It was the second time in two weeks

that a sudden, unexpected improvement in the weather had saved the day. Somebody up there must like Charlie Watson.

RESULTS