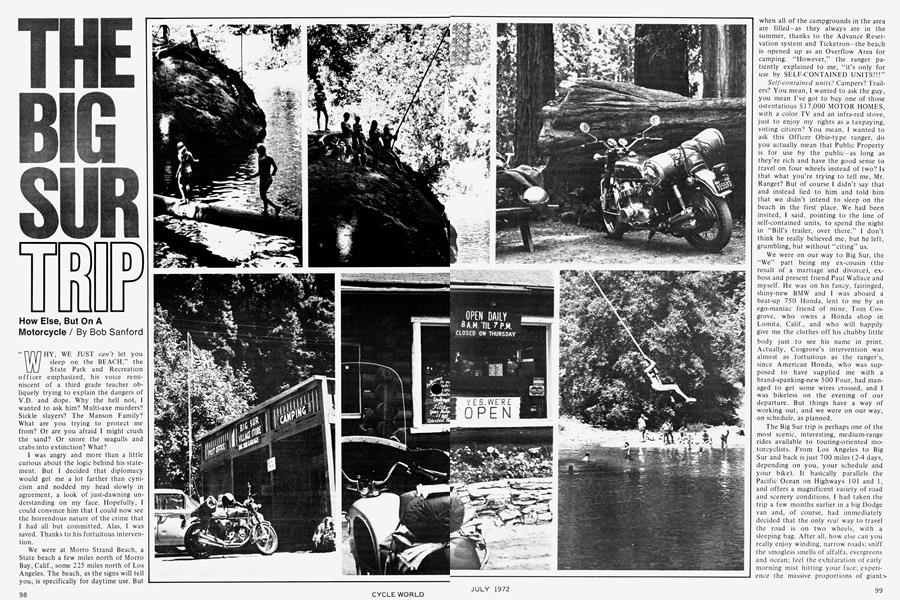

THE BIG SUR TRIP

How Else, But On A Motorcycle

Bob Sanford

“WHY, WE JUST can’t let you sleep on the BEACH,” the State Park and Recreation officer emphasized, his voice reminiscent of a third grade teacher obliquely trying to explain the dangers of V.D. and dope. Why the hell not, I wanted to ask him? Multi-axe murders? Sickle slayers? The Manson Family? What are you trying to protect me from? Or are you afraid I might crush the sand? Or snore the seagulls and crabs into extinction? What?

I was angry and more than a little curious about the logic behind his statement. But I decided that diplomacy would get me a lot farther than cynicism and nodded my head slowly in agreement, a look of just-dawning understanding on my face. Hopefully, I could convince him that I could now see the horrendous nature of the crime that I had all but committed. Alas, I was saved. Thanks to his fortuitous intervention.

We were at Morro Strand Beach, a State beach a few miles north of Morro Bay, Calif., some 225 miles north of Los Angeles. The beach, as the signs will tell you, is specifically for daytime use. But when all of the campgrounds in the area are filled—as they always are in the summer, thanks to the Advance Reservation system and Ticketron—the beach is opened up as an Overflow Area for camping. “However,” the ranger patiently explained to me, “it’s only for use by SELF-CONTAINED UNITS!!!”

Self-contained units? Campers? Trailers? You mean, I wanted to ask the guy, you mean Eve got to buy one of those ostentatious $17,000 MOTOR HOMES, with a color TV and an infra-red stove, just to enjoy my rights as a taxpaying, voting citizen? You mean, I wanted to ask this Officer Obie-type ranger, do you actually mean that Public Property is for use by the public-as long as they’re rich and have the good sense to travel on four wheels instead of two? Is that what you’re trying to tell me, Mr. Ranger? But of course I didn’t say that and instead lied to him and told him that we didn’t intend to sleep on the beach in the first place. We had been invited, I said, pointing to the line of self-contained units, to spend the night in “Bill’s trailer, over there.” I don’t think he really believed me, but he left, grumbling, but without “citing” us.

We were on our way to Big Sur, the “We” part being my ex-cousin (the result of a marriage and divorce), exboss and present friend Paul Wallace and myself. He was on his fancy, fairinged, shiny-new BMW and I was aboard a beat-up 750 Honda, lent to me by an ego-maniac friend of mine, Tom Cosgrove, who owns a Honda shop in Lomita, Calif., and who will happily give me the clothes off his chubby little

body just to see his name in print. Actually, Cosgrove’s intervention was almost as fortuitous as the ranger’s, since American Honda, who was supposed to have supplied me with a brand-spanking-new 500 Four, had managed to get some wires crossed, and I was bikeless on the evening of our departure. But things have a way of working out, and we were on our way, on schedule, as planned.

The Big Sur trip is perhaps one of the most scenic, interesting, medium-range rides available to touring-oriented motorcyclists. From Los Angeles to Big Sur and back is just 700 miles (2-4 days, depending on you, your schedule and your bike). It basically parallels the Pacific Ocean on Highways 101 and 1, and offers a magnificent variety of road and scenery conditions. I had taken the trip a few months earlier in a big Dodge van and, of course, had immediately decided that the only real way to travel the road is on two wheels, with a sleeping bag. After all, how else can you really enjoy winding, narrow roads; sniff the smogless smells of alfalfa, evergreens and ocean; feel the exhilaration of early morning mist hitting your face; experience the massive proportions of giant> redwoods and rolling, boulder-strewn hills; meet the people of the country’s nook and cranny towns, who shake their heads in bewilderment at the world-wise, young, long-haired travelers looking for themselves, their country, God, happiness and spare change; see where Man has preserved and Man has destroyed—where Man has erected, intentionally and otherwise, monuments and landmarks that are stepping-stone reminders of both the good and bad sides of his own culture construction? How else, but on a motorcycle?

For various reasons, we—rather, /—had decided to make the trip in 3-3V2 days, depending on conditions, and it was on our first night that the confrontation with Officer Obie occured. Leaving Los Angeles at about 9 a.m. that morning, we had freewayed our way north to Santa Barbara, where, a few miles outside of the city, we picked up Hwy. 154. You can continue north on 101, but 154 provides a lushly green winding trip through the Santa Ynez mountains and over San Marcos Pass. You also skirt along the edge of manmade Cachuma Lake and get a chance to take the Hwy. 246 cutoff into the little Danish community of Solvang. Which is exactly what we did, stopping in Solvang at lunchtime for a delicious cold cut sandwich and an ice-cold Tuborg beer. Even though the Danish community isn’t exactly My Kind Of Place, with its daily flocks of whiteChevy-station-wagon-families, it’s still a pretty town, with friendly people and delicious, reasonably priced food, not to mention a grand old 18th century Spanish mission.

At Buellton (home of the Split Pea Soup Kjng, Andersen, and his multiflocks of white-Chevy-station-wagonfamilies), we again picked up 101, passing through Santa Maria, Pismo Beach and, finally, San Luis Obisbo, where we took the Hwy. 1 cutoff into Morro Bay.

Although Morrow Bay depends largely on its increasing tourist trade, it is still pretty much a neat little fishing town—one of the few places, incidentally, where you can still catch sizable numbers of large bottom fish, such as grouper and snapper. The town sits at the mouth of a narrow, elongated bay, with miles and miles of rolling sand dunes and the enormous Morrow Rock keeping out the turbulent Pacific and providing a lake-like calm in the harbor. Restaurants, fish houses, docks and other businesses jut out into the channel, and I can tell you from experience that there are very few things equal to sitting in an over-the-water cocktail lounge, sipping your second martini, and watching the red-orange ball of sun slide behind the giant rock.

After being turned away from the filled-up Official State Campgrounds, eating a mess of fish and chips and noticing that the lead story in the local paper told of the concerted crackdown on beach sleepers (something, we later found out, prevalent in most coastal communities), I talked to a local antique dealer friend of mine, who informed us that there would be “absolutely no hassles” at Morro Strand Beach.

And we certainly believed him when we saw the 30 or so self-contained units stacked side-by-side in the paved parking lot. There was a Red Tide that night, which is not particularly good for the fish, but which makes the waves almost neon-bright with phosphorous. Besides that, it was warm, the sky was clear, down the way there was some guitar strumming around a campfire, and we knew, we just knew, that we were in for an enjoyable, peaceful, pleasant night. Which was really true, except for the brief brush with Obie and my partner Paul’s inability to sleep in the out-ofdoors.

After unloading our gear, laying out our sleeping bags and locking the bikes together, we made our way down to the campfire where the guitar was being strummed. Mostly, it seemed, there were young freaks sitting around smiling, singing and sharing a gallon of Red Mountain Wine. Introductions or doyou-mind-if-we-sit-downs never seem necessary at such gatherings, so we took a vacant piece of sand and began to listen to the guitars, harmonicas and young voices. Right away, we spotted Bill, moving through the crowd; patting backs and making inaudible comments.

Although Paul is in his forties and I am in my thirties, we both have longish hair and were wearing Clothes Of The Road and, at least to a degree, fitted in with existing conditions. Not so Bill. Bill, with his short, greasy hair and his Work Day clothes, was about as inconspicuous as Eldridge Cleaver in Beverly Hills. And he looked exactly like what he was: A truck driver from La Mirada, Calif. But, it turned out when Bill made his way over to our piece of sand, all of these people were with him! Hitchhikers he had picked up at various points along the way, shoving some in the back of his ancient pickup and the rest in the back of his more ancient 16-ft. house trailer. “Really like these kids,” he told us in a loud voice. “Remind me of my own.” And, indeed, he did seem genuinely fond of his young troops, and they him, as they shared their fifth gallon of Red Mountain of the day, as well as other pleasures of the youth culture. “How far you going?” I asked Bill. “Well,” he said, a sheepish smile on his face, “I was going to Oxnard.” A place he’d passed about 150 miles back down the road!!

Sometime during the evening, Obie paid us a visit and sometime later, much later, we found our way to the sleeping bags.

Early a.m. and we were up, shaking the cobwebs from our skulls and bungi cording our belongings to the bikes. The morning sky, as it always seems to be along the Pacific Coast, was low and overcast, keeping the blazing-bright sun off the multitude of young people still nestled in sleeping bags scattered helterskelter over the sand.

Before long we were blasting north through the heavy morning mist on Hwy. 1. Shortly, the freeway became history and we found ourselves switchbacking along a two-lane road, which exactly paralled the ocean, sometimes a distance of no more than 100 feet separating asphalt and water. It was cold and the mist kept my goggles clouded. But it was still breathtakingly beautiful, and I experienced one of those infrequent occasions known to all motorcyclists, when you feel a companionship with nature, when you experience a total calm, when you are absolutely content, when nothing can go wrong, when the power controlled by your right hand is working in perfect harmony with the elements under your wheels. For some reason, I fantasied myself hovering overhead in a helicopter, watching myself splitting the blacktop with my wheels, leaning over to the brinkat each sharp turn in the road, winding my way through the buffer zone between the choppy, emerald green pacific and the roly-poly brown hills. For a long while there were only two people in the world, myself on the bike and myself in the helicopter. Damn my mist-soaked jacket and clouded goggles. Damn the world’s Officer Obies. Damn everybody except the two of me.

Zoooooooom! Reality again, as a big semi lurched past, his vacumn rocking me back and forth. In a seemingly short period of time, we had covered more than 50 miles, and just ahead I could see the Santa Lucia mountains, which is the basis for the northernmost section of the Los Padres National Forest, as well as the southernmost home of the giant redwood trees. Not to mention, of course, Big Sur, which sits at the northern end of the mountain range, some 40-50 miles from our present location.

In a few minutes, we began to quickly gain altitude, as the two-lane road carried us back and forth up the side of the mountain, a solid mosscovered wall of rock on our right, a long and practically vertical drop to the Pacific on our left. The mist increased with each additional foot of altitude and finally I had to stop and take off my goggles. With the additional altitude and mist came additional cold and, frankly, that part of the ride was anything but enjoyable. After a cup of coffee at the single-store community of Gorda (one of about three or four places, incidentally, where you can buy food and gas between San Simeon and Big Sur), the sun made its first appearance of the day, making the rest of the trip into Big Sur more comfortable and, needless to say, more scenic. I made up my mind, though, that the return trip would be made at a later time of the day, so I could fully enjoy the ride and the Pacific Coast forest scenery.

(Continued on page 130)

Munching a noontime hamburger at a Mom & Pop restaurant in the Big Sur area, Paul decided that, for numerous reasons including his inability to sleep outdoors, he would head back home, possibly stopping at an el cheapo motel somewhere around San Luis Obisbo (as it turned out, he made it all the way home that night). But that wasn’t in my plans, so we amiably parted company.

Big Sur is actually a small village near the end of the Santa Lucia mountains, but most people refer to “Big Sur” as the area bordering Hwy. 1 for 10-15 miles south of the town itself. In many ways, it is the epitome of the Primeval Forest, with its gigantic, spiraling redwoods, its fern-filled underbrush, its clear, meandering, shallow, bubbling river. At certain times and in certain places, Big Sur is an eerie never-never land, where Man can sit feeling very infinitesimal in the presence of mighty, omni-present Nature, with Her vegetation reaching Her sky and providing the most basic of shelter for Her subject, Man. But Man had made his presence known in this Primeval Forest. He has dented Her surface with roads and restaurants, with campgrounds and houses, with litter and signs. He has carved an inroad, sliced Her belly open with asphalt and beckoned his species— for fun and profit. He has come to Her, marvelled Her beauty, built a center for Psychological Introspection—then built high fences and posted Keep Out signs around the Center’s perimeters. He has taken Her wood and built restaurants with hand-lettered posters that proclaim “No Damn Hippies Allowed.” He has seen Her Potential and brought in his iron and cement to create an organic Disneyland.

On the other hand, it is Man—or at least some men—who, with their laws on property and dogs and the cutting of timber, have protected the Big Sur area from Man, whose unleashed and unchecked fury can molest, rape and destroy Nature’s bounty. It is Man himself who has made rules and drawn the lines. It is Man himself who has kept Man from felling every bit of redwood and smothering the ferns with Coors cans. It is Man who has kept out the Freeways and kept the river clean. It is Man who has preserved the bit of Primeval, keeping out the Ticky-Tac houses and aerospace plants and Golden Arches. It is Man who has preserved Nature for me—Us—to enjoy.

(Continued on page 132)

So maybe, in the final analysis, it all works out. Maybe.

I got a campsite at the privately owned Big Sur Campground, where I paid $3 for 24 hours rent on a 10 by 12-ft. piece of ground, underneath a giant redwood and surrounded on three sides by self-contained units. Actually, it was a pretty nice place, with clean, working toilets and showers, a nice view of the Big Sur River, and a swimming hole, complete with a rope swing. I spent some time at the Village Store talking with some of the longhaired young people, many of whom regarded the Big Sur area as some sort of Mecca. And I met a very interesting, intelligent couple, who were staying at my campground and had arrived via a very righteous chopper that the man had built in three weeks time. Mostly, I just sat around, absorbing the beauty and thinking my thoughts.

I took my time packing and eating breakfast the next morning, hoping to outwait the cold and mist on the highway out of the mountains. Sure enough, I did, and sure enough, it was well worth the wait. On a nice day, that 40 mile stretch of pavement has to be one of the best pieces of motorcycling available to two-wheeling man. It is a seemingly never-ending series of upand downhill hairpins curves, skirting the edge of one of Nature’s heartiest growths of foliage, and overlooking—far, far down—Her enormous expanse of ocean.

Twenty-four hours later (I stopped in Pismo Beach for the night) I was home, a little bit weary and in some ways glad to be back. On the other hand, I was sorry it was over.

“Why don’t you,” I said to my wife at dinner that night, “get a few days off and we’ll go to Big Sur. Why, I’ll show you some things that. . . And, how else, but on a motorcycle? [5]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue