THE SCENE

IVAN J. WAGAR

WHILE MOST enthusiasts were on their way to Daytona early, I was in Japan. Not, unfortunately, to test some exciting new Superbike, but to talk motorcycle safety.

The tour was a U.S. Department of Transportation affair, consisting of Doug Toms, Bob Carter, Al Slechter and Lew Buchanan from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, and Trevor Jones and myself representing the National Motor Vehicle Safety Advisory Council. Inspection of Experimental Safety Vehicles (ESVs) was the main reason for the trip. Trevor went along because he is one of the world’s leading experts on crash sensors for airbag deployment, and has written several SAE papers on the subject.

Because the Administration now is interested in an Experimental Safety Motorcycle (ESM), as a Council member I went along to represent the best interests of industry and the motorcycling public. Some of the ideas on the “laundry list,” the name given to the list of proposed safety features of a possible ESM, are a bit far out, and would really hurt the manufacturers if they were required on all machines for production. Some of the ideas, such as anti-lock brakes, could be very good.

Good or bad, we should see some ESMs in the future. The one really good thing that will come out of the program is that we could see the manufacturers come up with good, hard research data that will shoot down some of the wild plans of some legislators about the need for seat belts and the like.

But the main reason I wanted to make this trip was to find out why motorcycle fatalities in this country are almost three times that of Japan, based on registrations. Japan has 8.5 million registered motorcycles, while we have about 3.5 million. Total motorcycle fatalities for 1971 were about the same for both countries.

Fortunately, we were able to visit a top motorcycle official in the National Police Agency, and he gave us the clue almost immediately: Rider Training and Licensing. In Japan, the police are Feds; that is to say that the police officers, except in some very remote areas, all work for a national agency. Thus there is uniformity in all police matters. All driver licensing is handled by the NPA, and licensing is very strict. It is not possible to just go down to your local DMV, fill out an application, ride around the parking lot and get your license. There is a requirement that you be a graduate of an NPA-certified driver or rider training school. Most of the schools are commercial ventures and require up to 30 hours training before an applicant qualifies for his license. The system works. Japan is one large traffic hazard. The streets and roads, except for a few expressways, are very narrow. Besides the problems of twoway traffic, there are concrete drainage ditches along the side. Blind intersections are the rule; traffic is everywhere.

Yet, with all these hazards, it is about three times safer to ride a motorcycle in Japan than in this country. Obviously good rider training and licensing is the key to safe motorcycling. The manufacturers recognize this fact and provide training facilities and instructors. Honda, for instance, developed a pilot training facility at Suzuka, the home of its famous racing plant. This program has been expanded to many parts of Japan and is very successful. No less than 600 of Yamaha’s district sales managers are certified driver licensing instructors.

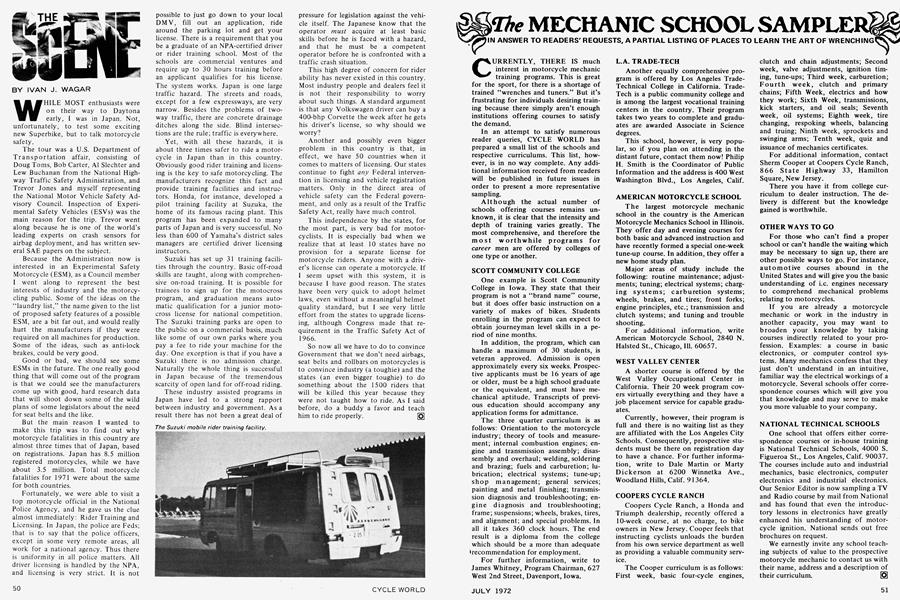

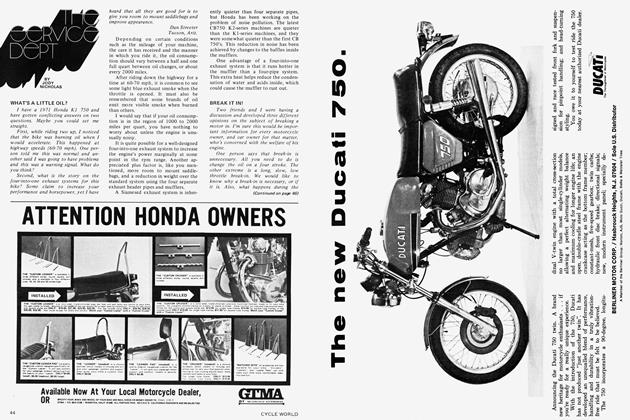

Suzuki has set up 31 training facilities through the country. Basic off-road skills are taught, along with comprehensive on-road training. It is possible for trainees to sign up for the motocross program, and graduation means automatic qualification for a junior motocross license for national competition. The Suzuki training parks are open to the public on a commercial basis, much like some of our own parks where you pay a fee to ride your machine for the day. One exception is that if you have a Suzuki there is no admission charge. Naturally the whole thing is successful in Japan because of the tremendous scarcity of open land for off-road riding.

These industry assisted programs in Japan have led to a strong rapport between industry and government. As a result there has not been a great deal of pressure for legislation against the vehicle itself. The Japanese know that the operator must acquire at least basic skills before he is faced with a hazard, and that he must be a competent operator before he is confronted with a traffic crash situation.

This high degree of concern for rider ability has never existed in this country. Most industry people and dealers feel it is not their responsibility to worry about such things. A standard argument is that any Volkswagen driver can buy a 400-bhp Corvette the week after he gets his driver’s license, so why should we worry?

Another and possibly even bigger problem in this country is that, in effect, we have 50 countries when it comes to matters of licensing. Our states continue to fight any Federal intervention in licensing and vehicle registration matters. Only in the direct area of vehicle safety can the Federal government, and only as a result of the Traffic Safety Act, really have much control.

This independence by the states, for the most part, is very bad for motorcyclists. It is especially bad when we realize that at least 10 states have no provision for a separate license for motorcycle riders. Anyone with a driver’s license can operate a motorcycle. If I seem upset with this system, it is because I have good reason. The states have been very quick to adopt helmet laws, even without a meaningful helmet quality standard, but I see very little effort from the states to upgrade licensing, although Congress made that requirement in the Traffic Safety Act of 1966.

So now all we have to do to convince Government that we don’t need airbags, seat belts and rollbars on motorcycles is to convince industry (a toughie) and the states (an even bigger toughie) to do something about the 1500 riders that will be killed this year because they were not taught how to ride. As I said before, do a buddy a favor and teach him to ride properly.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue