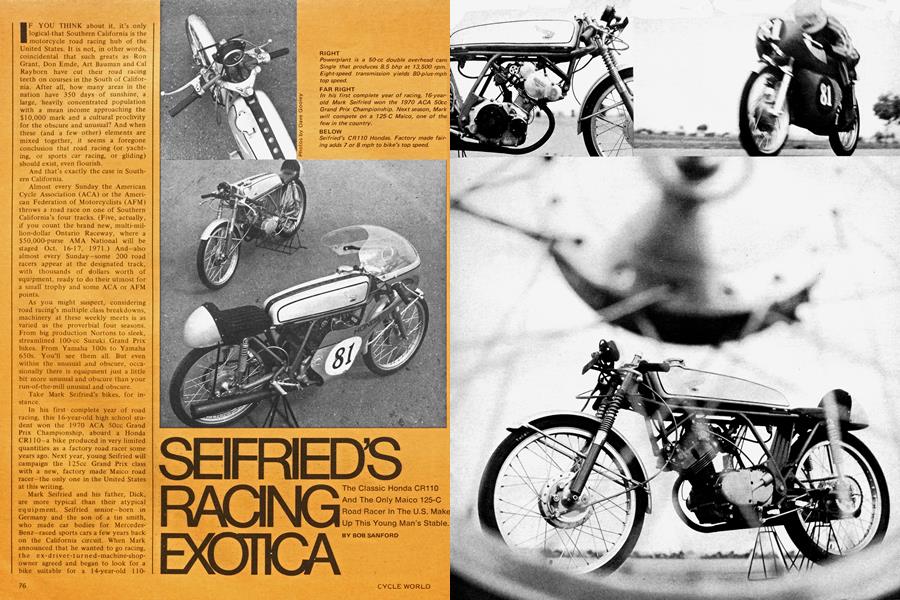

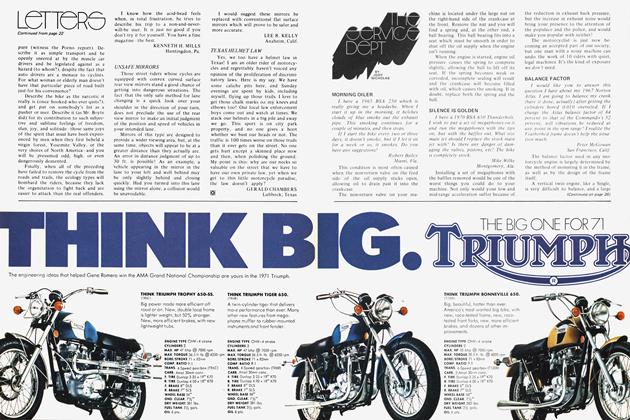

SEIFRIED’S RACING EXOTICA

The Classic Honda CR110 And The Only Maico 125-C Road Racer In The U.S. Make Up This Young Man's Stable.

BOB SANFORD

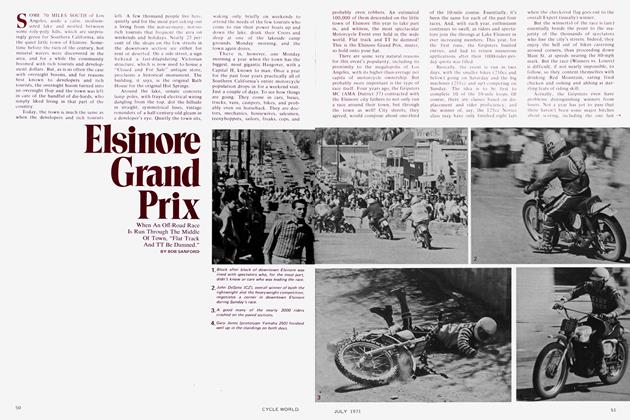

IF YOU THINK about it, it's only logical that Southern California is the motorcycle road racing hub of the United States. It is not, in other words, coincidental that such greats as Ron Grant, Don Emde, Art Bauman and Cal Rayborn have cut their road racing teeth on courses in the South of California. After all, how many areas in the nation have 350 days of sunshine, a large, heavily concentrated population with a mean income approaching the $10,000 mark and a cultural proclivity for the obscure and unusual? And when these (and a few other) elements are mixed together, it seems a foregone conclusion that road racing (or yachting, or sports car racing, or gliding) should exist, even flourish.

And that’s exactly the case in Southern California.

Almost every Sunday the American Cycle Association (ACA) or the American Federation of Motorcyclists (AFM) throws a road race on one of Southern California’s four tracks. (Five, actually, if you count the brand new, multi-million-dollar Ontario Raceway, where a $50,000-purse AMA National will be staged Oct. 16-17, 1971.) And-also almost every Sunday-some 200 road racers appear at the designated track, with thousands of dollars worth of equipment, ready to do their utmost for a small trophy and some ACA or AFM points.

As you might suspect, considering road racing’s multiple class breakdowns, machinery at these weekly meets is as varied as the proverbial four seasons. From big production Nortons to sleek, streamlined 100-cc Suzuki Grand Prix bikes. From Yamaha 100s to Yamaha 650s. You’ll see them all. But even within the unusual .and obscure, occasionally there is equipment just a little bit more unusual and obscure than your run-of-the-mill unusual and obscure.

Take Mark Seifried’s bikes, for instance.

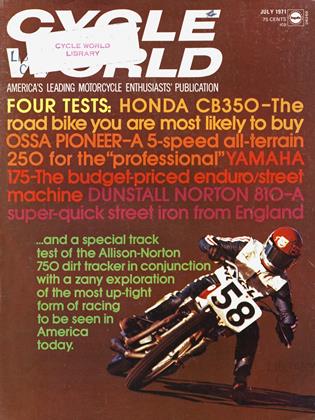

In his first complete year of road racing, this 16-year-old high school student won the 1970 ACA 50ec Grand Prix Championship, aboard a Honda CRI 10—a bike produced in very limited quantities as a factory road racer some years ago. Next year, young Seifried will campaign the 125cc Grand Prix class with a new, factory made Maico road racer the only one in the United States at this writing.

Mark Seifried and his father, Dick, are more typical than their atypical equipment. Seifried senior-born in Germany and the son of a tin smith, who made car bodies for MercedesBenz -raced sports cars a few years back on the California circuit. When Mark announced that he wanted to go racing, t he e x-d river-1 urned-machine-shopowner agreed and began to look for a bike suitable for a 14-year-old 110pounder. An old car racing acquaintance, Tom Barnes, of Trotman-Barnes, builders of Indy racing cars, had a CRI 10 that he intended to set up for an assault on the 50cc record at Bonneville. But at the time, he wasn’t interested in selling. Father Seifried, however, was interested in buying, and he began to look around for another such machine. And sure enough he found one owned by a San Fernando, Calif. Honda dealer, who collected old, interesting bikes as a hobby. Eventually, they made a deal and the Seifrieds were on their road racing way. A few months later, Barnes decided to sell his machine and Seifried & Son bought it as a back-up bike.

Honda made a handful of CR1 10s-anywhere from 14 to 200, depending on who you’re listening toin the early 1960s. Honda’s aim was to tear up 50cc European road racing, which they did rather successfully until a couple of Japanese two-strokes came along and blew them into the weeds. After that, about 1964, they threw in the towel and sold the bikes to enterprising privateers, such as the Seifrieds. The bike, however, is hardly a has-been or a piece of junk. No, indeed. “It's a beautiful thing,” says Dick Seitried, who understandably might be a bit prejudiced. “It’s like a gem. The workmanship inside is absolutely amazing.” Which could possibly account for the fact that Mark had no major mechanical problems last year and was beaten only twice.

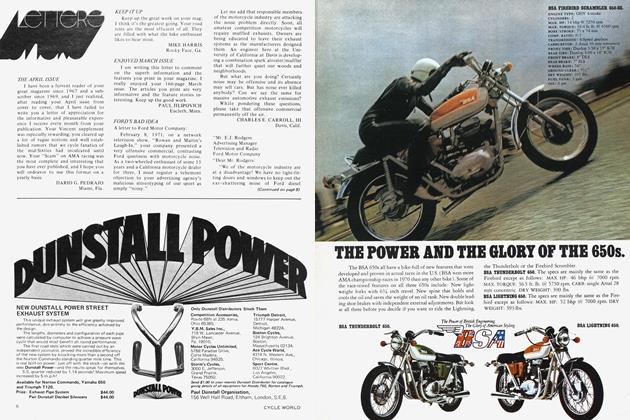

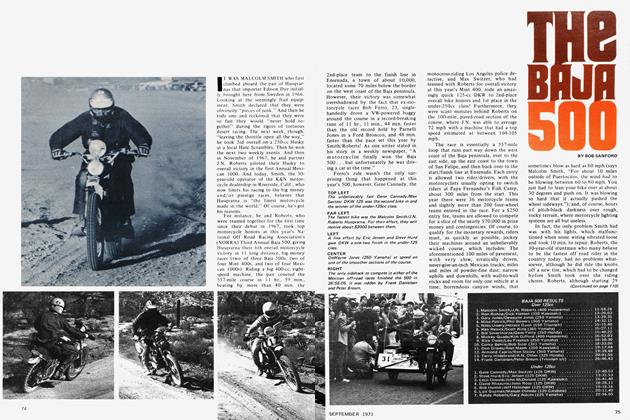

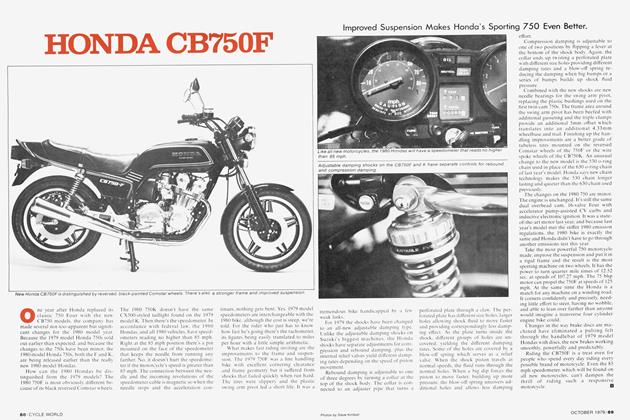

The Seifried’s two Hondas, still in virtual mint condition, are long, lean and gray in appearance. The early Honda wing insignia adorns the narrow 2.5-gal. tank. The factory-made, specially designed, wind-tunnel-tested fairing (original cost: around $250) adds to the sleekness, as well as to the performance. Dick Seifried estimates that the bike goes 7-8 mph faster with the special fairing. Surprisingly, other fairings they have tried produce speeds similar to those when no fairing is used. The frame is a double backbone arrangement, made of steel tubing and extending back past the rear shock, where the seat is mounted. The engine is a double overhead cam (one for intake, one for exhaust) Single, with a 1.5905 by 1.5354-in. bore and stroke, which produces 8.5 bhp at 13,500 rpm. The cams are gear driven and are supported on each end by ball bearings, while the crank and rod utilize roller bearings. Four valves are used for intake and exhaust. According to the senior Seifried, there is only about a 1000 rpm effective power range, between 12,500 and 13,500 rpms. Top speed is somewhere in the mid 80s.

One of the bike’s most unique features, however, is the eight-speed, constant-mesh transmission. Both Seifrieds are sold on this, although they admit that they are at a disadvantage to fewer-gear two-strokes on shorter courses. On long circuits, though, the little Honda eight-speed is at its best and makes good use of the super close ratios. A former road racer and first time rider of the CRI 10 was amazed at the ease of shifting. “It’s so easy to shift,” he remarked, “you don’t even lose 500 rpms between gears.” Plus, he added parenthetically, “It handles like a dream.”

Braking is internal expanding and is apparently one area where the bike is somewhat deficient. “The only thing I can criticize,” Dick Seifried says, “is that it’s marginal on braking power.” Unlike many road racers with internal expanding systems, including the new Maico, the Honda does not have air scoops for cooling the brakes.

Suspension is handled through a telescopic fork on the front and a swinging arm on the rear. Net weight is 134 lb. Wheelbase measures just a shade over 45

(Continued on page 125)

Continued from page 78

The Seifrieds had difficulty locating parts for the CRI 10 at first, but after a long, drawn-out letter-writing episode with the factory in Japan, they found out that parts for the machine had been sold to Honda Ltd. in London, England. Now, they are able to get required parts in about one week.

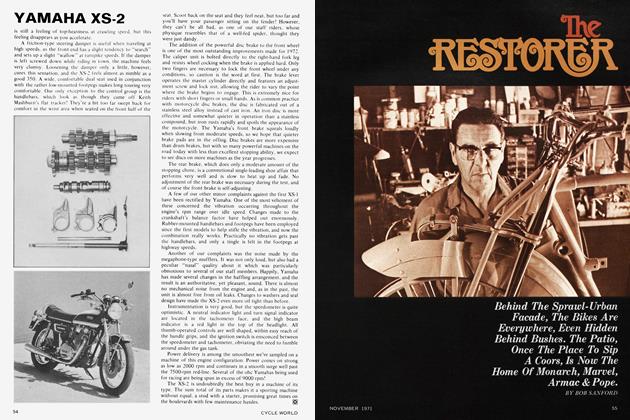

But the Honda was last year and the rider is this year. Nearly 15 lb. of flesh have been added in the interim; something that can make a sizeable difference in small bore competition. So the Seifrieds thought about the problem once again and arrived at the Maico RS 1 25-Cr. “1 hate two-strokes,” Dick Seifried confessed, after listening to the ear-splitting, high-rpm Maico. “The only reason 1 bought one is ’cause we can’t beat ’em with a four.” He had done his homework on small bore European road racing and concluded that the German machine was the up-and-coming hot set-up. So, he wrote to relatives in Germany, who contacted the factory, only to find out that prices were higher than if he were to order one directly from the U.S. distributor. Much time and many hassles with the distributor later, they finally got the machine, minus manuals, tools and instructions. But they’ve got it together (literally) now, and are convinced that the 28 blip produced by the 124-cc machine will keep them in the winner’s circle.

The rotary valve Single has a 2.128in. bore and stroke, a 14:1 compression ratio and turns a maximum 12,500 rpm. It has a six-speed transmission and a claimed top speed of 120 mph. The frame is double loop, net weight 146 lb., and the wheelbase is 51 in. A telescopic front fork and rear swinging arm handle the suspension chores.

As the Seifried's RS 1 25-C is the first of its kind in this country, the success or failure, or problems, with the machine pretty much remain to be seen. At best, it will be some time yet before road race freaks are dashing to their neighborhood dealer to buy one.

But what about next year, when Mark has another season of road racing and a few more pounds under his belt? What then? More exotic machinery? “Well,” says Dick Seifried. who, if first impressions have any merit, is a very easy going, not the least bit pushy, soft spoken guy, “It just depends on the boy. If he’s still interested, well, we'll go. As long as I’ve got the money,” he chuckles in his stoic kind of way. “Actually,” he adds not too convincingly, “I hope he loses interest. But if he doesn’t, well, we’ll find something.”