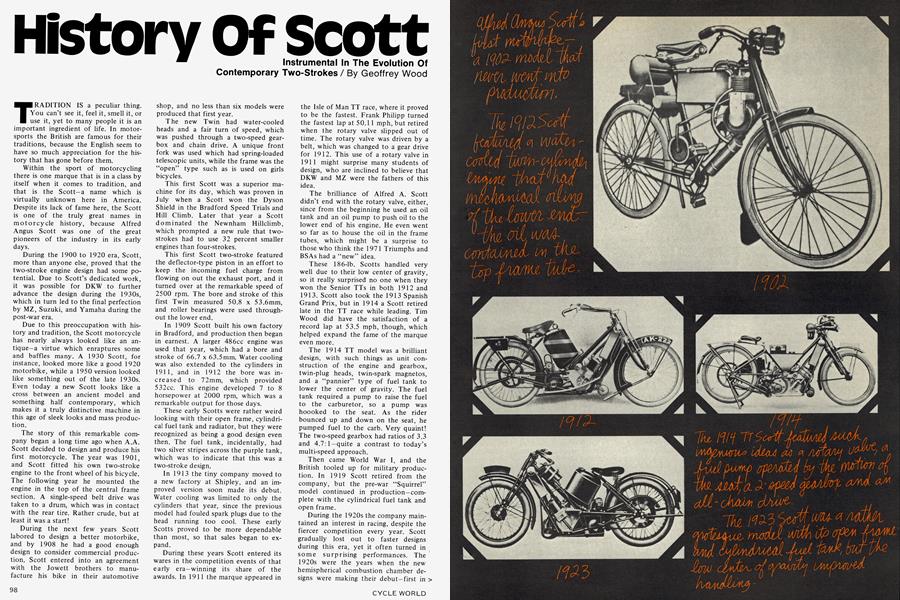

History Of Scott

Instrumental In The Evolution Of Contemporary Two-Strokes

Geoffrey Wood

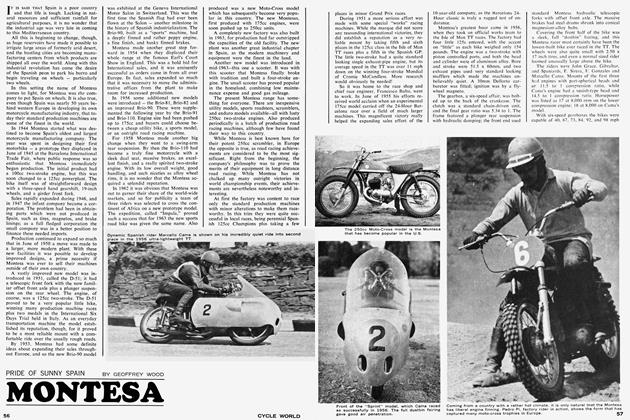

TRADITION IS a peculiar thing. You can't see it, feel it, smell it, or use it, yet to many people it is an important ingredient of life. In motor-sports the British are famous for their traditions, because the English seem to have so much appreciation for the history that has gone before them.

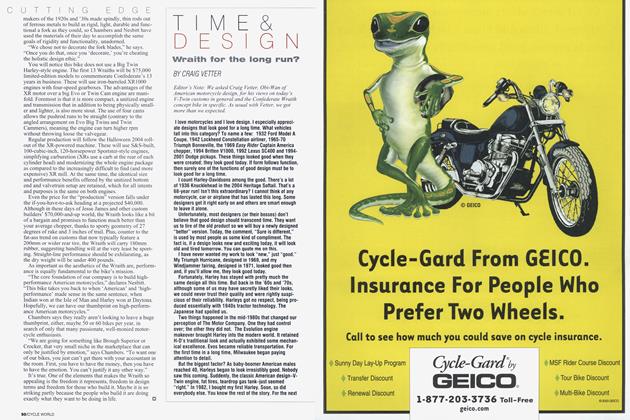

Within the sport of motorcycling there is one marque that is in a class by itself when it comes to tradition, and that is the Scott—a name which is virtually unknown here in America. Despite its lack of fame here, the Scott is one of the truly great names in motorcycle history, because Alfred Angus Scott was one of the great pioneers of the industry in its early days.

During the 1900 to 1920 era, Scott, more than anyone else, proved that the two-stroke engine design had some potential. Due to Scott’s dedicated work, it was possible for DKW to further advance the design during the 1930s, which in turn led to the final perfection by MZ, Suzuki, and Yamaha during the post-war era.

Due to this preoccupation with history and tradition, the Scott motorcycle has nearly always looked like an antique—a virtue which enraptures some and baffles many. A 1930 Scott, for instance, looked more like a good 1920 motorbike, while a 1950 version looked like something out of the late 1930s. Even today a new Scott looks like a cross between an ancient model and something half contemporary, which makes it a truly distinctive machine in this age of sleek looks and mass production.

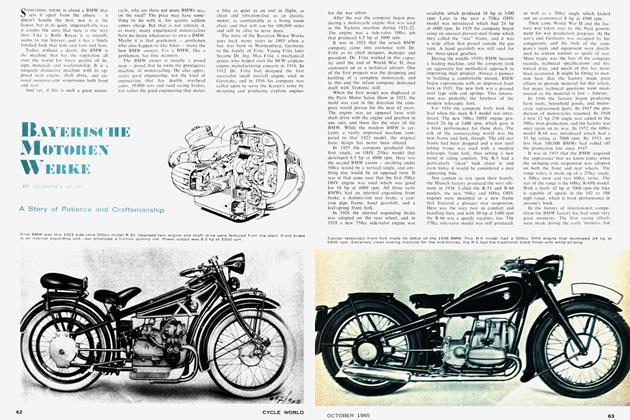

The story of this remarkable company began a long time ago when A.A. Scott decided to design and produce his first motorcycle. The year was 1901, and Scott fitted his own two-stroke engine to the front wheel of his bicycle. The following year he mounted the engine in the top of the central frame section. A single-speed belt drive was taken to a drum, which was in contact with the rear tire. Rather crude, but at least it was a start!

During the next few years Scott labored to design a better motorbike, and by 1908 he had a good enough design to consider commercial production. Scott entered into an agreement with the Jowett brothers to manufacture his bike in their automotive shop, and no less than six models were produced that first year.

The new Twin had water-cooled heads and a fair turn of speed, which was pushed through a two-speed gearbox and chain drive. A unique front fork was used which had spring-loaded telescopic units, while the frame was the “open” type such as is used on girls bicycles.

This first Scott was a superior machine for its day, which was proven in July when a Scott won the Dyson Shield in the Bradford Speed Trials and Hill Climb. Later that year a Scott dominated the Newnham Hillclimb, which prompted a new rule that twostrokes had to use 32 percent smaller engines than four-strokes.

This first Scott two-stroke featured the deflector-type piston in an effort to keep the incoming fuel charge from flowing on out the exhaust port, and it turned over at the remarkable speed of 2500 rpm. The bore and stroke of this first Twin measured 50.8 x 53.6mm, and roller bearings were used throughout the lower end.

In 1909 Scott built his own factory in Bradford, and production then began in earnest. A larger 486cc engine was used that year, which had a bore and stroke of 66.7 x 63.5mm. Water cooling was also extended to the cylinders in 1911, and in 1912 the bore was increased to 72mm, which provided 532cc. This engine developed 7 to 8 horsepower at 2000 rpm, which was a remarkable output for those days.

These early Scotts were rather weird looking with their open frame, cylindrical fuel tank and radiator, but they were recognized as being a good design even then. The fuel tank, incidentally, had two silver stripes across the purple tank, which was to indicate that this was a two-stroke design.

In 1913 the tiny company moved to a new factory at Shipley, and an improved version soon made its debut. Water cooling was limited to only the cylinders that year, since the previous model had fouled spark plugs due to the head running too cool. These early Scotts proved to be more dependable than most, so that sales began to expand.

During these years Scott entered its wares in the competition events of that early era—winning its share of the awards. In 1911 the marque appeared in the Isle of Man TT race, where it proved to be the fastest. Frank Philipp turned the fastest lap at 50.11 mph, but retired when the rotary valve slipped out of time. The rotary valve was driven by a belt, which was changed to a gear drive for 1912. This use of a rotary valve in 1911 might surprise many students of design, who are inclined to believe that DKW and MZ were the fathers of this idea.

The brilliance of Alfred A. Scott didn’t end with the rotary valve, either, since from the beginning he used an oil tank and an oil pump to push oil to the lower end of his engine. He even went so far as to house the oil in the frame tubes, which might be a surprise to those who think the 1971 Triumphs and BSAs had a “new” idea.

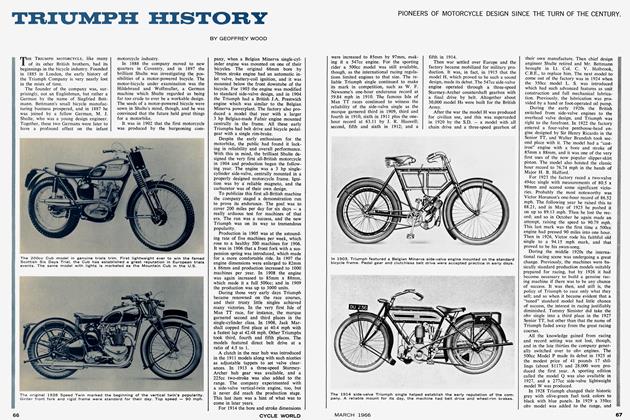

These 186-lb. Scotts handled very well due to their low center of gravity, so it really surprised no one when they won the Senior TTs in both 1912 and 1913. Scott also took the 1913 Spanish Grand Prix, but in 1914 a Scott retired late in the TT race while leading. Tim Wood did have the satisfaction of a record lap at 53.5 mph, though, which helped expand the fame of the marque even more.

The 1914 TT model was a brilliant design, with such things as unit construction of the engine and gearbox, twin-plug heads, twin-spark magnetos, and a “pannier” type of fuel tank to lower the center of gravity. The fuel tank required a pump to raise the fuel to the carburetor, so a pump was hoooked to the seat. As the rider bounced up and down on the seat, he pumped fuel to the carb. Very quaint! The two-speed gearbox had ratios of 3.3 and 4.7:1—quite a contrast to today’s multi-speed approach.

Then came World War I, and the British tooled up for military production. In 1919 Scott retired from the company, but the pre-war “Squirrel” model continued in production—complete with the cylindrical fuel tank and open frame.

During the 1920s the company maintained an interest in racing, despite the fiercer competition every year. Scott gradually lost out to faster designs during this era, yet it often turned in some surprising performances. The 1920s were the years when the new hemispherical combustion chamber designs were making their debut-first in > OHV form and then in OHC trim, which proved to be tough competition for the then inefficient two-strokes.

Despite its lack of speed, the 1921 Scott TT model was an interesting bike. The 73 x 62.5mm Twin had cast-iron liners in an alloy cylinder, while a single alloy casting was used for the head. A Lucas twin-spark magneto was used, and a two-speed gearbox plus a two-speed layshaft provided ratios of 3.3, 4.75, 4.95 and 6.4:1. The torque from the 500cc Twin must have been substantial to pull such tall ratios!

A 3-gal. fuel tank was set in the open frame, and a half-gallon oil tank was set just behind the magneto. The best place was a lowly 17th, though, which wasn’t very good for the Scott ego.

In 1922 the company reverted to its old iron-engine two-speeders, with Harry Langman finishing third at 56.09 mph, Clarrie Wood in fourth, and Geoff Clapham in ninth. In 1923 the company produced some special “long strokers”—still with a two-speed box, and managed to gain 11th and 18th places. A miniscule front brake was used for the first time in 1922.

All this racing activity had an effect on the production models, with a new three-speeder appearing that had water cooling added to the heads again. These Scotts, called the “Super Squirrels,” proved to be reliable models for their day, which by then had become a Scott tradition. The Super Squirrel was available in either 498cc (68.25 x 68.25mm) or 596cc (74 x 68.25mm) sizes.

Scott continued to enter the TT and other big races of the day, with Harry Langman taking second in the 1924 Senior TT at 61.23 mph. The two-speed model was run for the last time in the 1925 event, and Langman finished fifth that year. By then it was obvious to even the conservative people at the factory that a much better racing machine was necessary if the great Scott tradition of excellence was to be continued.

For 1926 a new racing model was produced that was quite a bit more modern looking, although we must admit that the Scott has never looked really modern. A new frame was used, which had two tubes at the sides of the engine plus a top tube over which the fuel tank was mounted. A new girder front fork was also adopted, which still had the long telescopic tubes from early Scott practice, while a three-speed gearbox was featured in place of the outdated two-speed approach. The gearbox was shifted by hand, and larger brakes were adopted due to the increased speeds. Despite its technical appeal, the water-cooled two-stroke was a dismal failure that year.

In 1928 Scott gained its last real success, when Tommy Hatch finished third in the TT on his Twin. These 1928 models were long strokers with measurements of 66.6 x 71.4mm, and they also had a new large and squarish fuel tank which would be continued on the roadsters until 1950. The fuel tank and radiator are now considered to be the most appealing parts of a great classic.

No radical changes were made for 1929, but larger fuel and oil tanks were fitted to cope with increased fuel consumption, and the filler caps were then placed on the left side to speed up refills in the TT. The magneto was also moved closer to the crankcase, thus enabling a shorter chain to be used. Thirteenth place was the best that year, which was the last time that a works Scott was to finish a TT.

All of this racing activity benefited the man-on-the-street, though, since Scott introduced its “TT Replica” model for 1929—a model for the enthusiast who didn’t mind paying a premium price for a super sporting roadster. The 500cc TT Replica had a bore and stroke of 66.6 x 71.4mm, while the big 600 measured 73 x 71.4mm. A three-speed gearbox with ratios of 4.4, 5.8 and 9.35 was used, along with a new girder front fork and a rigid frame. The classic fuel tank held 3.0 gal., and the fueled weight was 330 lb. Large brakes, measuring 8.0 in. rear and 7.0 in. front, were usedcomplete with a set of cooling fins on the rear drum. The tire size was 3.00-20 in.

The standard models then were the trusty old two-speeder plus a new “Flying Squirrel” model, which was a threespeeder introduced in 1927. The Flying Squirrel had the racing type frame and formed the basis for Scott production until 1950. The two-speed model was finally dropped in 1930.

In 1930 the company tried its hand at producing an inexpensive 300cc Single, which had a three-speed Sturmey-Archer gearbox. The little Single was produced for just a few years, and then it was dropped—despite having performed well in the rugged and now classic Scott Trial.

A radically new (for Scott!) racing model was produced for the 1930 TT, which dispensed with the sloping cylinders in favor of a vertical engine. The alloy crankcase had three compartments—one for each cylinder and one for the central flywheel. The driving sprocket was moved to the right side of the case instead of the center of the engine, and a four-speed gearbox was used for the first time. The idea was to cure the burnt pistons and lower ends that had stopped so many TT Scotts, but a bad vibration prevented the new racer from ever getting past the practice period.

Despite the TT failure, Scott forged ahead with its 1930 range of models as never before. There were 500 and 600cc twoand three-speed touring models, the 300cc Single and the sports models. The touring versions used the short stroke engines, while the sports models used the long stroke “Power Plus” engines.

Among the sports models was an interesting bike for speedway racing. This trim beast had a light fork and frame, knobby tires, and a tuned engine. The Speedway model was produced to special order, but the history books don’t list any great successes.

Perhaps the pride of the range then, and certainly the most valuable today to collectors, was the “Sprint” model. This mount was intended to be a light, fast sports model with brisk acceleration. A buyer could order his Sprint in varying degrees of tune, and he could also specify the open frame and cylindrical fuel tank or the more orthodox fuel tank over the top frame tube. The Sprint was hand-assembled at the factory with loving care, so it is no surprise that is was one of the fastest roadsters going then. In grass track racing and hillclimbs (the British type up winding roads), the Sprint gained an impressive list of victories.

The economic depression finally caught up with the company in 1931, which forced it to go to more modern production practices as well as a standardization of models and parts. In 1932 the Single was dropped, so that the only sizes available were 500 and 600cc.

In 1933 the economic woes had lessened a trifle, which encouraged the company to design a super luxurious roadster. The new tourer was a 747cc in-line three, but it was never put into production. Instead, a larger 986cc version was produced in very small numbers during 1934, 1936, and 1937. An optional spring frame was tried on the three, which never seemed to tickle the public’s fancy.

During the 1930s Scott was not able to contest the TT or grand prix events due to its limited financial position, but it did produce some production racing models for the private owner which had a fair turn of speed. This model was called the “Grand Prix,” which had strengthened cranks, a four-speed foot shift gearbox, and a speed of around 100 mph. During the late 1930s Scott lapped the old Brooklands track at 95 mph, which was the best it ever did at the speed bowl.

By 1935 the Flying Squirrel had been cleaned up in detail until it looked reasonably sharp. The rigid frame and girder front fork provided a rather rough ride, but such improvements as three-speed footshift gearbox and hand clutch made for good control. The gear ratios of the 500 were 4.62, 8.12 and 13.3, while the big 600 packed ratios of 4.18, 7.35 and 12.2:1. The weight was 310 lb., and the top speeds were listed as 70 and 75 mph on the two models.

The TT Replica model was also available with a tuned engine, 8.0-in. rear brake, larger 3.0-gal. fuel tank and many special parts that made it suitable for high speed road work or racing. The weight was 330 lb., and the gearbox had ratios of 4.4, 5.8 and 7.75:1.

During the 1930s the international racing scene became terribly competitive. The German and Italian governments poured money into their companies’ racing programs, which put the small concerns, such as Scott, out of the racing business. Speeds increased dramatically during the 1930s, and the overhead cam four-stroke became undisputed master. DKW was the only one to get a two-stroke in the winner’s circle, and this was done by using the loop scavenging principle (patented at the works by Dr. Schnurle), supercharging, water cooling and a rotary valve.

Against such a background it was obvious that Scott stood little chance of success, so it decided to concentrate on designing better road and sports models. One of these sports models was the 193 9 “Clubman’s Special”—a 596cc mount that was intended to be a roadster for those who like to play road racer in their riding.

The new Clubman model had a tuned engine that shoved out 3 1 horses, which propelled the bike to over 90 mph. Rear springing was optionally available, which boosted the weight from 411 lb. in rigid frame trim to 490 lb. The Clubman had two oil pumps—one to push oil to the lower end and the other to oil the cylinder walls. The bore and stroke was 73 x 71.4mm, and the deflector type pistons were still used.

The company also produced a 98cc engine unit for bicycles, which proved to be a popular method of transport in England just before the war. The company even showed a healthy profit in the last few years before the war, which was the first time in many years. Then came World War II, and Scott turned its attention to the war effort.

After the war Scott resumed production with a 600cc Flying Squirrel that differed little from the 1939 model. In 1947 a Dowty telescopic front fork was used in place of the old girder fork, and dual 6.0-in. brakes were featured on the front wheel. The Dowty fork was unique in that it used air and oil for compression and rebound damping. In 1949 the BTH magneto was dropped in favor of a battery and coil ignition system, and an alloy full-width hub was added to the rear wheel.

The Flying Squirrel continued in production for two more years, with a reputation, as always, for reliability and an archaic appearance. Operating on a modest compression ratio of 6.9:1, the Twin produced 30 bhp at 5000 rpm. The top speed was listed as 80 mph— still using the venerable old three-speed gearbox.

Despite its reliability and great tradition, the Scott Company was in deep financial trouble due to a low sales volume and high costs in a terribly competitive market. In 1950 the axe fell with official bankruptcy, and production then ceased at the Shipley works. It looked as if a colorful tradition was dead.

Not quite dead, however, since a loyal enthusiast of the marque named Matt Holder came forward to buy up the name and rights of production. Harry Longman, the old TT rider, joined with Matt, and together they fitted the pieces together to keep the name alive.

The new “parent” company was Aereo Tool and Jig Company; and, after a few years spent in getting tooled up for production, Scotts were again available to enthusiasts all over the world. After several moves the company finally settled down in a new factory in Birmingham, where Matt turned his attention to improving the breed.

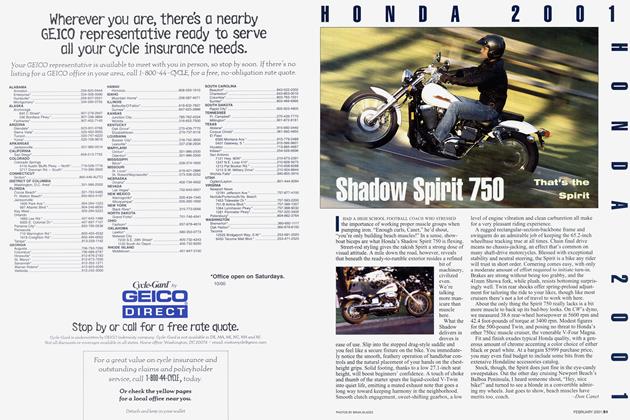

Scott lovers have some rather conservative ideas about “improvements,” though, so Matt wisely took a conservative line. A new swinging-arm frame with a normal spring-oil telescopic front fork made its debut in 1956, and this was topped off with a traditionally shaped fuel tank. A four-speed gearbox was also added, which made the Scott of the 1960s seem reasonably modern. The 600cc engine was virtually the same engine as used since 1947, though, and it continued to be famous for its reliability.

The Flying Squirrel is still in production, too, but only on a limited basis in small numbers. To obtain one of these illustrious classics one must convince Matt Holder that he is a worthy owner who appreciates the history and tradition behind the great name. I am told this is no easy chore.

There is one other interesting chapter of the Scott story, and this is the tale of the new 344cc road racer—a model designed in the mid-1960s. The racer departs from Scott tradition with its air-cooled engine, which operates on 12.5:1 compression ratio and a pair of 1.25-in. bore Amal GP carburetors. The bore and stroke is square at 60.25mm, and an orthodox gas-oil mix is used for lubrication.

The performance through an Albion five-speed box is quite competitive, since the engine spins freely to 9000 rpm. The standard gear ratios are 4.95, 5.4, 6.4, 7.4 and 10.7:1. A leading-link front fork is used on this 252-lb. Twin, which has 3.00 and 3.25-18 tires.

The output by 1971 was up to 45 bhp at nine grand, which propelled the bike to speeds of 125 mph on the short British circuits. Ridden by Barry Scully, the Scott has racked up many impressive showings in British events the past six years. The company has also designed a larger water-cooled 500 for Scully to ride, but more development work is needed to make the bigger two-stroke competitive.

Today, the Scott is an enigma in the world of motorcycling. There are, for instance, more Scotts officially registered with the Vintage Motor Cycle Club of England than any other make, yet outside of England the marque is barely known. Here in America there are few enthusiasts who have even heard of the name, yet the contemporary two-stroke owes much of its history to Alfred Angus Scott.

The preservation of these colorful old classics is the work of many historically knowledgeable enthusiasts all over the world, and especially the Scott Owners Club of England. This fine organization, founded in 1958, now has over 500 members all over the world, including around a dozen loyal devotees of the marque here in America. The club produces a fine magazine called the “Yowl,” a name which comes from the delightful ripping howl that the classic Scotts made on a racing course. I also must mention the dedicated work done by Ron Mountain, editor of the magazine, to research and locate the material and photographs for this story. There are few who will do this much work for the honor of their marque.

What the future is for the company no one really knows, but already there is enough history behind the Scott to make it a great chapter in the evolution of the motorcycle. The man who rides a Scott today has one of the most reliable motorcycles ever built. More important, though, is the tradition involved in owning a Scott, for a ride on one of these waterpumpers is just like riding something out of the past. Some will appreciate this tradition and some will not, but for those who do it is like the aroma and taste of a fine wine. Nostalgia. [o]