MONTESA

PRIDE OF SUNNY SPAIN

GEOFFREY WOOD

IT IS SAID THAT Spain is a poor country and that life is tough. Lacking in natural resources and sufficient rainfall for agricultural purposes, it is no wonder that the industrial age •was very late in coming to this Mediterranean country.

All this is beginning to change, though, as huge reservoirs have made it possible to irrigate large areas of formerly arid desert, and the bustling cities are becoming manufacturing centers from which products are shipped all over the world. Along with this industrial revolution has come the desire of the Spanish peon to park his burro and begin traveling on wheels — particularly two wheels.

In this setting the name of Montesa comes to light, for Montesa was the company to put Spain on wheels. It is also true, even though Spain was nearly 50 years behind western Europe in developing its own motorcycle manufacturing industry, that today their standard production machines are some of the finest in the world.

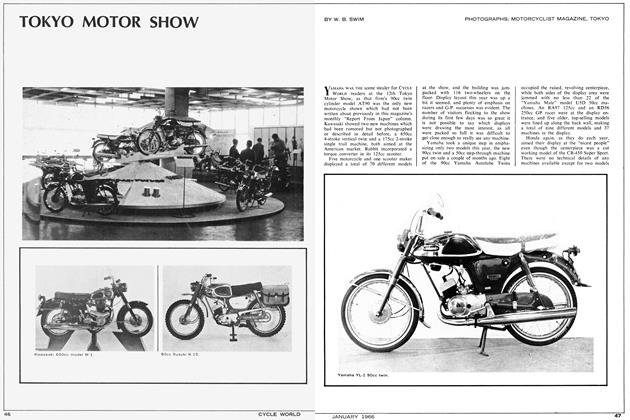

In 1944 Montesa started what was destined to become Spain’s oldest and largest motorcycle manufacturing company. The year was spent in designing their first motorbike — a prototype they displayed in June of 1945 at the Barcelona International Trade Fair, where public response was so enthusiastic that Montesa immediately *began production. The initial product had a lOOcc two-stroke engine, but this was soon changed to a 125cc powerplant. The bike itself was of straightforward design with a three-speed hand gearshift, 19-inch wheels, and a girder front fork.

Sales rapidly expanded during 1946, and in 1947 the infant company became a corporation. The problem had been in obtaining parts which were not produced in Spain, such as tires, magnetos, and brake linings; as a full fledged corporation the small company was in a better position to finance these needed imports.

Production continued to expand so much that in June of 1950 a move was made to a larger, more modern plant. With these new facilities it was possible to develop improved designs, a prime necessity if Montesa was ever to sell their machines outside of their own country.

A vastly improved new model was introduced in 1951, called the D-51; it had a telescopic front fork with the now familiar offset front axle plus a plunger suspension on the rear wheel. The engine, of course, was a 125cc two-stroke. The D-51 proved to be a very popular little bike, winning many production machine races plus two medals in the International Six Days Trial held in Italy. As an everyday transportation machine the model established its reputation, though, for it proved to be a most reliable mount with a comfortable ride over the usually rough roads.

By 1953, Montesa had some definite ideas about expanding their sales throughout Europe, and so the new Brio-90 model was exhibited at the Geneva International Motor Salon in Switzerland. This was the first time the Spanish flag had ever been flown at the Salon — another milestone in the history of Spanish industrialization. The Brio-90, built as a “sports” machine, had a deeply finned and rather peppy engine, a fine finish, and husky finned brakes.

Montesa made another great step forward in 1954 when they displayed their whole range at the famous Earl’s Court Show in England. This was a bold bid for International sales, and it was eminently successful as orders came in from all over Europe. In fact, sales expanded so much that it was necessary to move the administrative offices from the plant to make room for increased production.

In 1956 some additional new models were introduced — the Brio-81, Brio-82 and an improved Brio-90. These were supplemented the following year by the Brio-91 and Brio-110. Engine size had been pushed up to 175cc and buyers could choose between a cheap utility bike, a sports model, or an outright road racing machine.

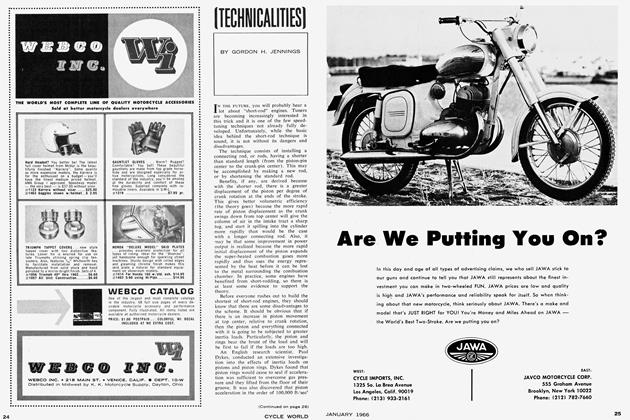

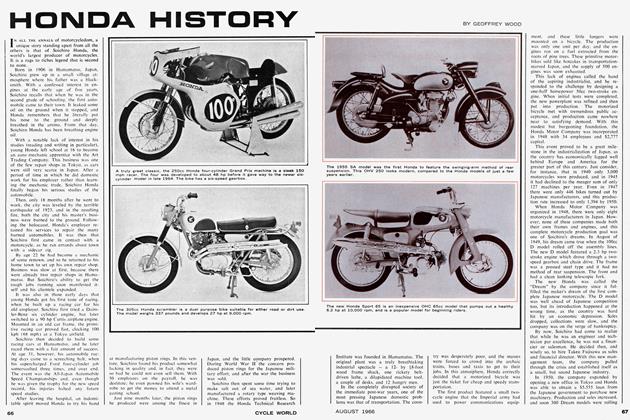

For 1958 Montesa made another big change when they went to a swing-arm rear suspension. By then the Brio-110 had become a truly fine motorcycle with a sleek dual seat, massive brakes, an excellent finish, and a really spirited two-stroke engine. With its low overall weight, good handling, and such niceties as alloy wheel rims, it is no wonder that the Montesa acquired a splendid reputation.

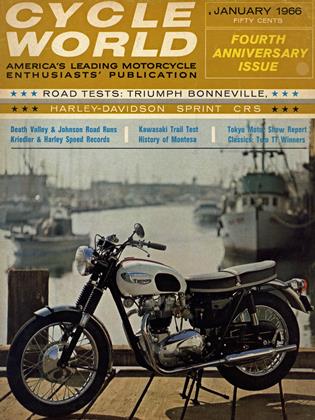

In 1962 it was obvious that Montesa was out to garner their share of the world-wide markets, and so for publicity a team of three riders was selected to cross the continent of Africa on a new prototype model. The expedition, called “Impala,” proved such a success that for 1963 the new sports road bike was given the same name. Also produced was a new Moto-Cross model which has subsequently become very popular in this country. The new Montesas, first produced with 175cc engines, were soon pushed up to 250cc units.

A completely new factory was also built in 1963, for production had far outstripped the capacities of the old facility. The new plant was another great industrial chapter in Spain, as the modern machinery and equipment were the finest in the land.

Another new model was introduced in mid-1963—this one a scooter. It was with this scooter that Montesa finally broke with tradition and built a four-stroke engine. The small scooter has proved popular in the homeland, combining low maintenance expense and good gas mileage.

The present Montesa range has something for everyone. There are inexpensive utility models, sports roadsters, scramblers, and enduro models available—all with lusty 250cc two-stroke engines. Also produced periodically is a batch of production road racing machines, although few have found their way to this country.

While Montesa is best known here for their potent 250cc scrambler, in Europe the opposite is true, as road racing achievements are considered to be the most significant. Right from the beginning, the company’s philosophy was to prove the merits of their equipment in long distance road racing. While Montesa has not chalked up many outright victories in world championship events, their achievements are nevertheless noteworthy and interesting.

At first the factory was content to race only the standard production machines with minor alterations to make them raceworthy. In this trim they were quite successful in local races, being perennial Spanish 125cc Champions plus taking a few places in minor Grand Prix races.

During 1951 a more serious effort was made with some special “works” racing machines. While the marque did not score any resounding international victories, they did establish a reputation as a very reliable mount by taking fifth and sixth places in the 125cc class in the Isle of Man TT races plus a fifth in the Spanish GP. The little two-stroke had a quite standard looking single exhaust-pipe engine, but its average speed in the TT was over 11 mph down on the winning four-stroke Mondial of Cromie McCandless. More research would obviously be needed!

So it was home to the race shop and chief race engineer, Francesco Bulto, went to work. In June of 1955 his efforts received world acclaim when an experimental 175cc model carried off the 24-Hour Barcelona race over a field of much larger machines. This magnificent victory really helped the expanding sales effort of the 10-year-old company, as the Barcelona 24Hour classic is truly a rugged test of endurance.

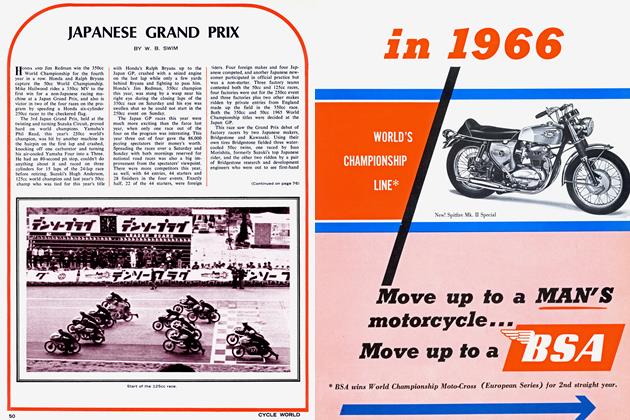

Montesa’s greatest hour came in 1956, when they took an official works team to the Isle of Man TT races. The factory had four little 125s entered, with the accent on “little” as each bike weighed only 154 pounds. The engine was a two-stroke with piston controlled ports, and both the head and cylinder were of aluminum alloy. Bore and stroke were 51.5 x 60mm, and two exhaust pipes used very standard looking mufflers which made the machines unbelievably quiet. A 30mm Dellorto carburetor was fitted; ignition was by a flywheel magneto.

The gearbox, a six-speed affair, was bolted up to the back of the crankcase. The clutch was a standard chain-driven unit, and the final gear ratio was 5.34 to 1. The frame featured a plunger rear suspension with hydraulic damping; the front end used standard Montesa hydraulic telescopic forks with offset front axle. The massive brakes had steel drums shrunk into conical magnesium-alloy hubs.

Covering the front half of the bike was a sleek, full “dustbin” fairing, and this Montesa racer must certainly have been the lowest-built bike ever raced in the TT. The wheels were also quite small with 2.50 x 17 inch tires, and even a normal sized rider loomed unusually large above the bike.

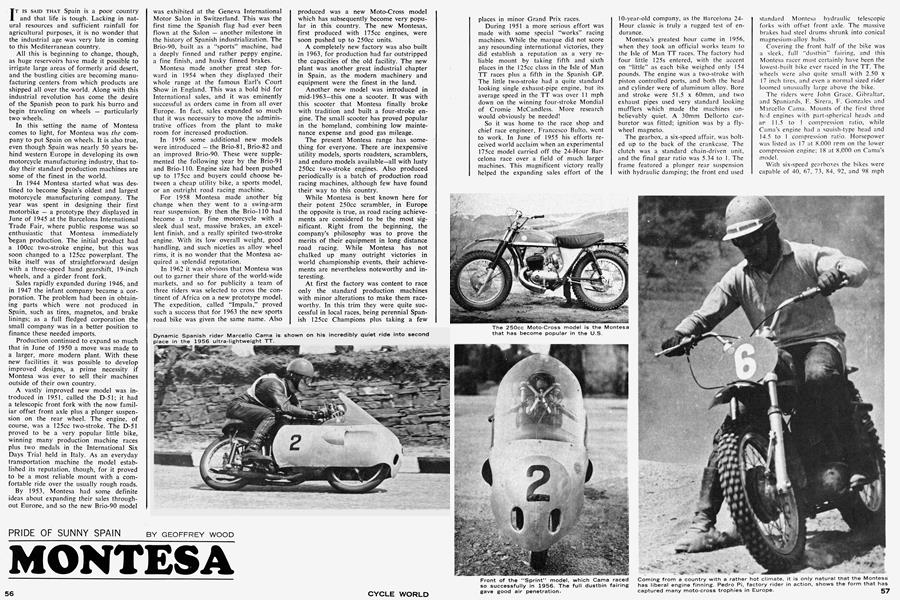

The riders were John Grace, Gibraltar, and Spaniards, F. Sirera, F. Gonzales and Marcello Cama. Mounts of the first three had engines with part-spherical heads and ar 11.5 to 1 compression ratio, while Cama’s engine had a squish-type head and 14.5 to 1 compression ratio. Horsepower was listed as 17 at 8,000 mm on the lower compression engine; 18 at 8,000 on Cama’s model.

With six-speed gearboxes the bikes were capable of 40, 67, 73, 84, 92, and 98 mph at 8,000 rpm through the gears. The experimental high-compression engine was noted as having better acceleration than the others, and Cama could squeeze 8,200 revs out of it on the level for an even 100 mph.

Lubrication was provided by mixing S.A.E. 40 mineral oil with the gasoline at a 1 to 25 ratio. An auxiliary oil tank fed castor oil into the carburetor intake at 10 drips per minute for extra upper end lubrication. Fuel consumption was 40-45 mpg.

In the race itself the Montesa team had formidable opposition from the MV Agusta, F.B. Mondial, and CZ. Reliability had its day though; one by one the faster Italian machines dropped by the wayside until Cama came home second at 65.24 mph behind Carlo Ubbiali who won at 69.13 mph. Gonzales and Sirera brought the other Montesas in third and fourth, and John Grace retired with clutch trouble. The balance of the season saw a few more “places,” then Montesa decided to quit GP racing and concentrate on production racing-bike development.

Later that year the company began limited production of the 125cc “Sportsman” model — a pukka racer that has established an enviable reputation for reliability at speed. The Sportsman differs little from Cama’s old 1956 works bike, except that the compression ratio is 12 to 1 and a smaller 27mm carb is used. The model also has an improved expansion box exhaust system which helps pump out the 18 hp at 8,000 rpm. A modern swingingarm frame is fitted, and the brakes are housed in beautiful full-width alloy hubs.

Since the factory has decided to concentrate its efforts on developing “over-thecounter” competition machines, their international racing record has become impressive. The 1956 and 1963 Barcelona 24Hour races went to Montesa, as well as many 125cc, 175cc, and 250cc Championship events in France, Chile, Mexico, Paraguay, Uruguay and Spain. It vis in the endurance events that the Montesa continues to shine, and in 1964 the marque took third in the Barcelona classic behind a works 285cc ohc Ducati and a 600cc BMW. The 250cc Montesa won its class by no less than 29 laps over its nearest competitor that year — a true measure of reliability.

This past June the company wanted very badly to win the 24-Hour Barcelona classic again, since 1965 is Montesa’s twenty-year anniversary. A team of factory riders mounted special “prototype” models, and high hopes were voiced that the larger engined bikes could be#worn down on the twisty 2.35-mile long Parque de Montjuich course.

The race was led early by a works 650cc Triumph, but it dropped out and the two 250cc Montesas of Jose Busquets/Cesar Gracia, and Jorge Sirera/E. Sirera came to the lead ahead of the Norton, Triumph, Velocette and BMW teams. At the thirteenhour mark Jorge Sirera punctured a tire and fell, injuring his arm and breaking the handlebar. After a one-hour stop he was back in the race.

At the fifteen-hour mark Busquet’s Montesa came into the pits, also for a one-hour stop. This put a 650cc Dresda/Triton (a Triumph engine in a Norton chassis with Oldani hubs) into the lead which it held to the end. A privately entered 250cc Montesa came second—only three laps behind, and Montesa also took the first three 250cc places. A gallant effort by a courageous little factory!

The 250cc-and-over leader board of the 1965 Barcelona 24-Hours race follows:

So this, then, is the story of Montesa, an industrial pioneer in sunny Spain. It is the saga of putting a nation on wheels, and of building a motorbike that is one of the very best in the world today. Just think of the obstacles to overcome in bringing forth such an outstanding machine in such a short period of time from a country so poor as Spain. It is like starting to race when you don’t even have your engine running and the other fellow is already doing 100 mph — and you want to catch up and then pass him.

It is beautiful to see a country turn green from irrigation, and a people go from poor to well fed and full of life. In all of this Montesa has played a big part; no wonder Spain is smiling. Look again at the Barcelona Endurance Race results — then reflect that 21 years ago there was not a single bike being manufactured in Spain. Some of the best from Europe and Japan ran at Barcelona last June—and many of them had a 50-year head start.