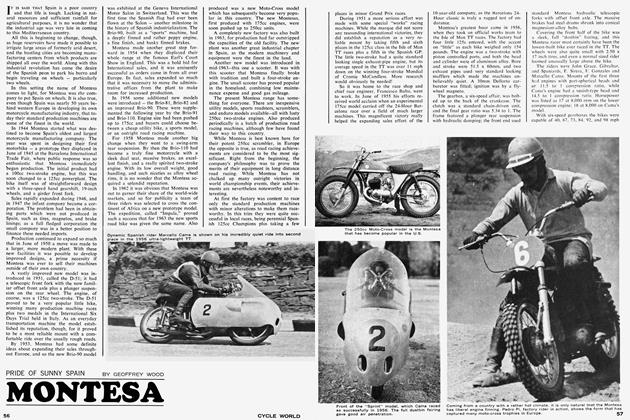

MOTO GUZZI HISTORY

A Great Legacy of Exotic Racers

IN THE GREAT SAGA of international motorcycle racing there are many colorful chapters, but for pure nostalgia and exotic machinery none can equal the story of the Moto Guzzi. Not a common machine in the Americas, this Italian marque has its home on beautiful Lake Como in northern Italy, and the story of its life is one of the most colorful and intriguing in all the world.

Italy has traditionally been a rather poor country, and the benefits of the industrial revolution were rather late in coming to its people. When mechanization finally came, though, it was carried on with such fervor that Italy’s motorcycles became pre-eminent on the European classical road racing courses, as well as being some of the finest in the world for day-to-day transportation. An important part of this rise in industrialization was the legend of the Guzzi — a story that put the Italians on wheels, made the company the best seller in its land, and brought home the prestige of many world championships.

This great legend all began way back in the days of World War I, when Giorgi Parodi and Giovanni Ravelli were flying airplanes in defense of their country and the two flyers’ planes were serviced by a young technician named Carlo Guzzi. This particular mechanic could talk about nothing except his dream of building the finest motorbike in all the world. In offduty hours, Carlo would sketch out his design while the two flyers listened. And Ravelli, being an experienced motorbike racer, voiced the opinion that the design had great merit.

So, after the war, Carlo Guzzi and Giorgi Parodi got together on the project and laid plans for the new G & P motorcycle. The emblem selected for the new make was an Eagle with its wings spread wide in flight. This was out of respect for brother Ravelli, who had lost his life in action.

The first problem was to raise the capital to begin operations, so Parodi went to his father who was a man of some means. The necessary finances were duly obtained (some 2000 lire) and the elder Parodi promised more, if the experiments proved successful.

Later, with a few employees, a waterwheel powered lathe, and a lot of determination, the two young industrialists went to work. Their course was quite clear then, as Italy produced virtually no motorcycles and her export business was non-existent. In this atmosphere, one would think that chief engineer Guzzi would have stuck to orthodox or proven design principles, but this was not the case, and his approach was to be a really fresh one to the problem.

In the December 15th issue of Motociclismo, the new machine was announced publicly, and the name changed to Moto Guzzi. The specifications were rather advanced for those early days, and also very different, but on this design, the infant company was to stake its future. The frame and fork were quite standard for those early days, but the single cylinder engine was mounted horizontally in the frame. Not only was that unusual, for the flywheel was mounted outside of the crankcase instead of inside.

The valve gear was the inlet-over-exhaust arrangement, which meant that it had an “overhead” inlet valve and a “side” exhaust valve. The engine capacity was 500cc, and a hand shift and chain drive were featured. The front wheel had no brake and the rear wheel used an internal expanding brake.

Now, one of the principles that has historically been associated with Guzzi has been that racing improves the breed, and so this “La Prima” model received an early baptism. Aldo Finzi is the name that the history books mention with a win at the famous Targo Florio circuit, but it was really the amazing stamina of this new machine that impressed the public.

Not content to sit on his laurels, Carlo kept at his design work, and in 1923, he produced a new overhead valve engine* as well as a production racing machine to go with the standard road model. This new 500cc model also featured the horizontal engine with the tiny crankcase and outside flywheel and it, too, was soon entered in the great homeland races to prove the brilliance of its design. And it won, taking trophies at Concorso Di Consumo, Giro d’ Italia, Pinerolo-Costagrande and Del Lario.

These early successes went a long way in proving the genius of this young Ing. Guzzi, and public demand for his products rapidly increased. Once again, new designs came off the drawing boards, and this time a 250cc single joined its 500cc older brother. The new engines featured a bevelgear-driven overhead cam, and four valves were used along with two exhaust pipes. The girder fork was retained on the front and an internal expanding brake was still used on only the rear wheel. The frame was the old “vintage era” type with the gas tank between two top frame tubes and the oil tank mounted on top of that.

These 1924 models were raced with great success in Italy. Then, in September, the Guzzis were prepared for their first international race — the Grand Prix of Europe at Monza. Despite the really fierce opposition from all the leading factories in Europe, the marque scored a smashing victory. Guido Mentasi took first, E. Visioli garnered second and Pietro Ghersi captured third — a truly remarkable achievement for such a tiny factory.

This great international victory put the company firmly on the map and sales rapidly expanded. For 1925, a new “Peoples Sport” model was introduced which had the I.O.E. type of engine, lights, and a three-speed hand gearshift.

A few years later, in 1928, the engineering progress was really manifest when the 500cc “Sport 14” and “Grand Turismo” models were announced. The engines were a new ohv design with a hemispherical combustion chamber, and much larger fins were used to dissipate the heat, A dynamo was fitted for the lighting system and a magneto was used for ignition. Lastly, internal expanding brakes were finally fitted to both wheels, which made the bike much safer to ride.

A definite attempt was also made to improve rider comfort as a more modern girder fork with both compression and rebound springs was used. It was the Grand Turismo model that really made the news for rider comfort, as it included a method of rear suspension in its specifications. The springing was effected by having a triangulated rear sub-frame which was pivoted at its top joint to the main frame and with the lower arm connected to a long springbox that ran completely underneath the engine. This was probably the first really successful spring frame on a motorcycle, and it was truly a great milestone in engineering progress.

The following year, the factory again made great strides in producing a good machine for the public. Use of the motorcycle for both sport and transportation was on the increase, and the public demanded a more reliable mount that was capable of genuine touring. Guzzi responded with a new range of 250 and 500cc models for 1929, and one of the most notable changes was the new triangulated cradle frame that had the “saddle” type gas tank mounted over the top frame tube with the oil tank beneath the gas tank.

GEOFFREY WOOD

That same year Carlo Guzzi manufactured his first motorcycle-truck combination — a type of machine that is still produced today. The idea was sound, since Italy was still a rather poor country, and this inexpensive method of hauling materials was just the ticket for the businessman.

The furious design improvement pace was maintained and during the early 1930s, many new models were introduced. The 1931 “Sport 15” model proved to be particularly popular; its clean lines were a big improvement over the earlier models. By 1934, a customer had his choice of a 175, 250 or 500cc Guzzi in standard trim, with a spring frame, or to road racing specifications.

The 500cc production racing model achieved many successes during the late twenties and early thirties in continental grand prix events and national championships, but the marque had failed to score any really big victories that would enhance export sales. The traditional oversquare ohc 500cc single with measurements of 88 x 82mm bore and stroke was pumping out only about 97 mph in 1930, so the factory decided to put more emphasis on some new designs that would set the racing world on fire.

In 1933, the work began on a new 500cc twin that was destined to usher in an exciting new era for the company, as well as take them to the summit of motorcycle racing — the Isle of Man TT. It was not until 1935 that they actually got there, and that year happened to fall in the middle of the era when anyone with any sense at all left the all-conquering Norton strictly unchallenged.

Norton had a famous Scot by the name of Jim Guthrie, who piloted his singles with such skill that he simply squashed the opposition into embarrassing second places. Realizing full well that it would take a truly great rider, plus a mighty fast Guzzi, to upset this reigning world champion, the factory hired one Stanley Woods to do the coup de grace. Stanley was, in his own right, a formidable contender, having won more races and TTs than anyone else, but to trounce the Norton on its home ground was asking quite a bit.

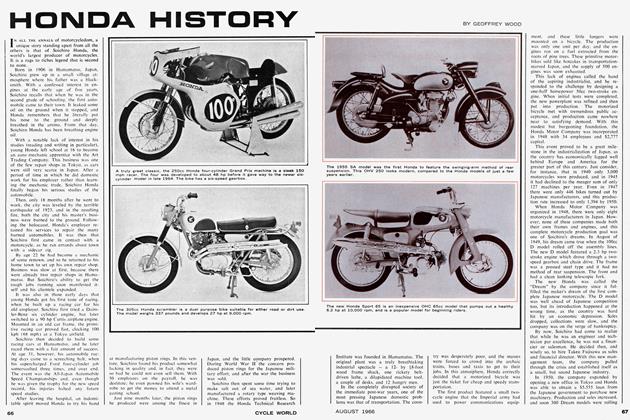

The new Guzzi, though, was quite a racing machine. The basic design was a wide angle (120-degree) V-twin, which was rumored to have offset cranks so that it fired at 180 degrees. Bevel gears and shafts drove the single overhead cams, and hairpin valvesprings were used. The engine produced about 44 hp at 7,500 rpm for a maximum of 112 mph, which was about equal to the Norton single.

The front fork was an orthodox girder type, but the rear wheel had a very unusual feature for the race track — a type of pivoted fork suspension. The fork was a triangulated affair similar to that used on the 1928 GT model, but the spring boxes were mounted beneath the rear fork, so that the spring unit moved with the fork. A springer had never won a Senior TT, and it was generally agreed that the handling would never be good enough and the whole plot would be unstable at speed. This suspension, incidentally, could have its damping altered during the race by simply moving a lever on the left side of the bike.

The other specs on the twin were equally impressive. A massive brake was fitted to the front wheel which had twin leading shoes, a four-speed footshift gearbox was used, and straight pipes were used instead of megaphones. Another innovation was alloy wheelrims — a move to cut down unsprung weight as well as lessen the revolving weight that the brakes must stop.

And so it was. The race began as everyone thought it would, with Guthrie leading Woods by 28 seconds. On the second lap the margin was 47 seconds, and on the third lap it was 52. Then, on the fourth lap, Stanley began to creep up and the clocks showed only 42 seconds difference. On the fifth it was 29 seconds, and on the sixth it was 26. Still, 26 seconds was a very substantial margin to make up on such a brilliant rider as Guthrie, so it looked like another Norton win.

At the end of the seventh lap, Guthrie wheeled in to be acclaimed the winner, the wreath was placed around his neck, champagne was uncorked, and the Island’s Governor gave Jim his congratulations. Guthrie, by virtue of his starting number one, was the first to finish, while Woods was well back in the pack on a much later starting interval. So, all there was for Jim to do was to watch Stanley’s clock and see just how bad he had him beat.

Then began the drama. Into the last lap went Stanley, his torso glued to the top of the tank and the V-twin turned up to a noticeably higher speed. Faster and faster he went, and the revs mounted to 8,000. From curb to gutter the Guzzi was flung and the seconds were slowly pegged back'

— one by one. Silently in his pits, Jim Guthrie watched as Stanley and the Guzzi gained. Soon he came into sight and screamed past the checkered flag.

It took a few minutes to calculate, but then came the announcement that Stanley had smashed the lap record by nearly four miles per hour on his last lap and so had won the Senior TT by four tiny seconds. Overnight the marque became famous, as Stanley had also won the Lightweight TT on his little single. A new era was born.

Back in Italy, the factory expanded its plant facilities to keep pace with the demand for their products, and soon the roadsters were featuring such race-proven features as footshifts, powerful brakes, speedy ohv engines and superb roadholding.

In the race shop the midnight oil was burned and many brilliant designs were produced. Probably the most successful was the ohc 250cc single which won many races, as well as setting a speed mark of 132.2 mph in the hands of R. Alberiti, and a standing start kilometer record of 25.45 sec. (88.18 mph average) by G. Sandri. This little 250 featured a supercharger, which is one of the few blown singles to ever be successful, and it even scored an astounding first and second place in the 1939 German Grand Prix when Nello Pagani and Sandri trounced the reigning world champion DKWs.

Another blown Guzzi was the 1940 three-cylinder model, a 500cc beast that never saw many races because of World War II. Probably the prettiest of the lot was the 1939 Condor, a 500cc production racer that established a splendid reputation in the hands of private owners. The Condor featured the pivoted-fork rear suspension pioneered on the 1928 GT model

— one of the first uses of a spring frame on a production racer.

Then came the war and all motorcycle racing and most motorcycle production was halted in Italy. After the war, the factory was soon into production; many new street models were produced in sizes ranging from 65cc on up to 500cc. Scooters, motorcycle-trucks, 250cc roadsters, 500cc roadsters, and production road racers were all manufactured, and the marque’s sales hit a new high as exports spread all over the world.

Probably the most popular Guzzi was the 250cc Airone Sport, a race-bred model that provided a spirited 80 mph top speed combined with powerful brakes and a good suspension. The Airone featured an ohv engine with bore and stroke of 70 x 64mm, and the powerplant acquired a reputation of being unburstable.

The 500cc models were the Astore (touring) and the Falcone (a sports model), and these Guzzis were known for their excellent roadholding and tireless high cruising speeds. The Falcone was clocked at 98 mph in European road tests, but few ever made their way to America.

In the late 1950s, the horizontal singles were phased out and new, more modern looking vertical-mounted engines made their debut. These new scooters and bikes up to 250cc have maintained a healthy sales figure and have continued the Guzzi reputation of quality engineering. Realizing that perhaps something was lost when the big singles were dropped, the factory recently began production of a 700cc Vtwin, which was originally intended for police use.

The marque also resumed racing activities after the war and their successes reached a new high. A new 250, the Albatross, made its debut in 1945, and the model was also sold as a production racer. The Albatross was a cobby looking little hike, with its traditional ohc horizontal engine, unusual pivoted-fork rear suspension, and the girder front fork. The engine turned to 8,000 revs and produced 24 hp, good enough for a speed of 102 mph.

The 250’s bigger brother was the Dondolino,< a 500cc model that also was available to the private owner. A really great classic of a racing bike, the big single never did achieve the aura of invincibility that surrounded the Albatross. The 250 literally dominated its class in 1947 and 1948, with the 500 scoring a few victories such as the 1947 Swiss and 1948 Ulster classics.

For 1949, the marque once again introduced new singles, both as works and production racers. The new 250 was called the Gambalunghino and the 500 was named the Gambalunga, which meant simply “little long leg” and “long leg.” These two bikes continued the Guzzi tradition of winning races. Also raced in those early postwar days was the old V-twin, which had undergone a great deal of development. The twin’s power was down to something like 42 at 6,800 rpm, though, as the postwar switch from petrol-benzol fuel to just plain “pool” gas forced a drastic lowering, of compression ratios.

The twin did not fare too well in those days, as the reliability was not up to the standard of the singles. In the 1948 Senior TT, for instance, Omobono Tenni had a big lead at the end of the fourth lap until one cylinder failed and he toured home in ninth position. Then, in 1949, Bob Foster was way out in front with only a lap and a half to go when the clutch gave up. The development work went on, however, and in 1952, the engine was producing 48 hp at 8,000 rpm for a top speed of 129 mph. The twin did gain many good “places” in those years, but the factory decided that the one win in the 1951 Swiss GP was not enough to keep the model in the lineup.

The little 250 single did much better, and its reputation as a winner was sealed with such victories as the 1949, ’51, ’52 and ’53 Lightweight TTs, the World Championship in 1949 (Bruno Ruffo), 1951 (Ruffo), and 1952 (Enrico Lorenzetti), and many hundreds of minor grand prix events. The Gambalunghino, by 1952, was producing 27 hp at 7,500 rpm on its 8.7 to 1 compression ratio, and this was good enough for a 109 mph top end. The little racer was noted for its fine handling, its unique feature of the gas tank being streamlined for the rider’s arms., the leading link front fork, a massive front brake, and the horizontal engine with its outside flywheel.

About that time, the leading designer at the factory, Ing. Giulio Carcano, decided to join the Italian trend to four cylinders — only with a difference — as the Guzzi four had the engine mounted in line with the frame. Shaft drive and water-cooling were adopted, as was a partial “dolphin” type of fairing. The new four had a very advanced dohc head with fuel injection, and four short straight pipes were used. The four was very fast and it won its first race at Hockenheim in 1953 when Lorenzetti romped home at an average speed of 107.8 mph. After that initial success the four turned out to be totally unreliable and it was soon dropped.

A far more successful chapter was the quest of the 1953 World Championship in the Junior (350cc) Class. Fergus Anderson was on the team then, and, after his record breaking rides in the 1952 and 1953 Lightweight TTs, he urged Carcano to scale up his 250 into a 350. The first step was to increase the 68 x 68mm engine to a 72 x 80mm size, which gave 320cc. This move was eminently successful and Fergus garnered a third in the Junior TT and then a win at Hockenheim.

(Continued on page 96)

Justifiably encouraged, the factory enlarged the engine in mid-season to a 75 x 79mm 350, and power was thus raised from 28.5 at 8,400 rpm to 31 at 7,700. The weight of this Junior model was a very light 264 pounds, and the maximum speed was an amazing 130 mph. This terrific speed on only 31 hp was due to another great Guzzi engineering achievement — streamlining. The racers that year showed the results of many hours spent in the wind tunnel on airflow studies, and the full “dustbin” fairing gave excellent air penetration. On this speedy 350, Fergus Anderson easily won the World Championship.

For 1954, the valve sizes were increased to 37mm for the inlet and 32mm for the exhaust, a 35mm carburetor was fitted, and the compression ratio was 9.5 to 1. Power output was 33.5 at 7,500 rpm. Anderson was again successful and one more World Championship came home to Mandello del Lario.

In 1955, the brilliance of Ing. Carcano was once again manifest when the racers appeared with a new and very light “space ’ frame that was designed to fit the dustbin fairing. The engine was also modified to a 80mm bore and a 69.5 stroke, the valves enlarged to 41 and 36mm, and the carburetor increased to 37mm. The head featured two spark plugs, battery ignition replaced the magneto, and the compression ratio was 9.4 to 1. And then, lastly, the head was modified to a double overhead cam setup; all these improvements helped boost power to 35 at 7,800 rpm.

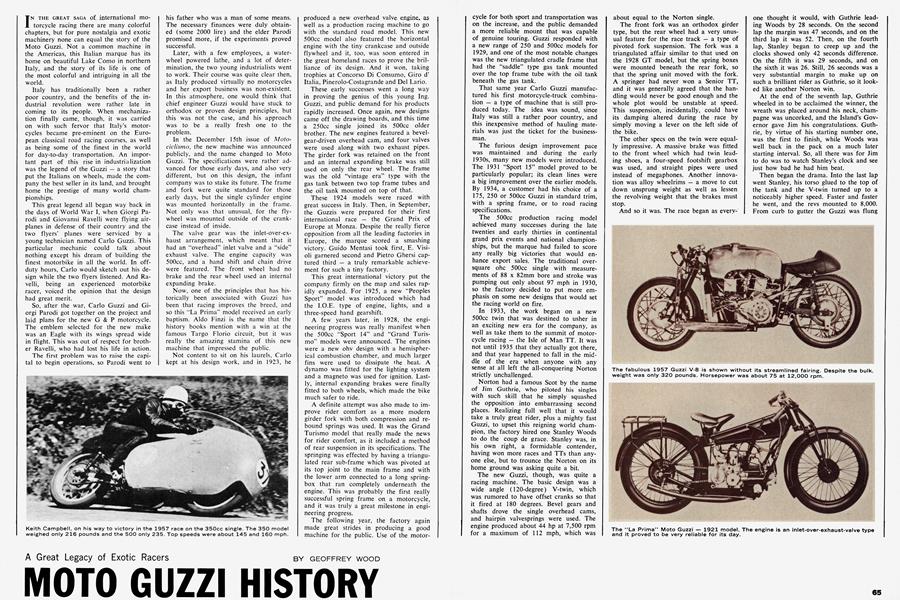

Bill Lomas was the first-string rider for 1955 and 1956 and he easily won the 350cc world titles, but on the tighter courses the new engine had actually lapped slower than the old long stroke engine. Ing. Carcano once again made some changes for 1957 when he went back to the 75 x 79mm measurements with 39 and 33mm valve sizes. One spark plug was used and ignition was by a magneto. Power output was up to 38 at 8,000 rpm and the medium speed torque was much improved. The weight of these racers was fantastically light, with the 350 weighing only 216 pounds and a larger 500 model just 20 pounds more.

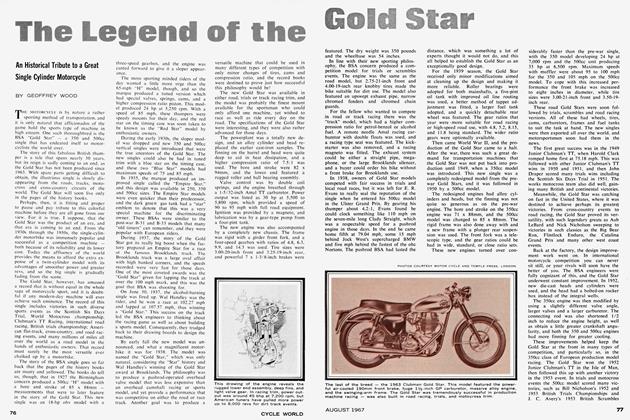

Carcano’s genius, however, did not end here, for he was hard at work designing the fastest road racing motorcycle that the world has ever seen. First raced in 1956. it was not until 1957 that the world found out just how fast this new 500 was. The basic design was a dohc 90-degree V-8 with the tiny measurements of 44 x 41mm bore and stroke. Eight 20mm carburetors were used as were eight short exhaust pipes, and water-cooling was also employed.

The engine was mounted transversely in the frame and chain drive was used. The frame was similar to that used since 1953 on all Guzzi racers, with a swinging-arm rear suspension and a leading link front fork. Massive brakes were fitted to cope with the colossal speed. The weight was actually quite light at 320 pounds, but the sheer bulk of the bike made it appear much heavier.

It is only natural that many teething troubles cropped up on such a complex machine, and lap records, rather than race records, fell to the V-8. The horsepower in 1956 was listed as 62 at 12,000 rpm, which provided a 162 mph top end on a 6.1 to 1 gear ratio. This speed, however, was with the dolphin-type of streamlining, and it was not until one year later that the fabulous eight was to truly show its speed.

The venue was the beautiful Spa-Francorchamps course in Belgium, which is terribly fast with its 100 mph corners and long straights. Keith Campbell, from Australia, was the first-string rider that year, and his skill was never in doubt, as he had already trounced the best in the 350cc class. But would the new V-8 hold together long enough to actually win a race?

The flag fell and away went the field with such stars as Libero Liberati on his Güera, John Surtees, MV Agusta, and Walter Zeller, BMW. It was soon apparent that the 75 hp the V-8 developed, combined with the full dustbin fairing, gave Campbell the speed he needed to sear through the field and take the lead. On and on Keith rode, smashing the lap record again and again, until he turned in his finest hour with a 118.56 mph lap. Then, just after he was clocked at a fantastic 178 mph on the fast Masta straight, Campbell came to a halt with gearbox trouble.

And so ended the last great chapter of the fabulous Moto Guzzi V-8, for little did the half-million spectators know that an era was ended. For at the season's end, the beloved racing Guzzis, along with their World Champion brothers, the 125 and 250cc Mondial and 500cc Güera, announced that they were withdrawing from racing. It seemed impossible at first that Guzzi could really mean this, for their heritage of racing since 1921 was one of the greatest, and certainly among the most colorful, that has ever existed.

We realize now, of course, that the real cause for their decision was not within their control. As Italy prospered in the post-war economy, her people switched from motorbikes to cars, and this does not help a motorcycle company’s profits any. It takes great sales and huge profits to design a modern-day racing bike and then take it all over the world to do battle.

Sadly, it all came to an end. The men, the great races, and the romantic machines — it is all just a legend now. But while it lived, it was one of the really fascinating stories of our century, and the uninhibited engineering and beautifully exotic racing bikes will probably never be equaled.

From 1921 through 1957 -a truly re markable record. For their honor, I list it below: