BAYERISCHE MOTOREN WERKE

GEOFFREY WOOD

A Story of Patience and Craftsmanship

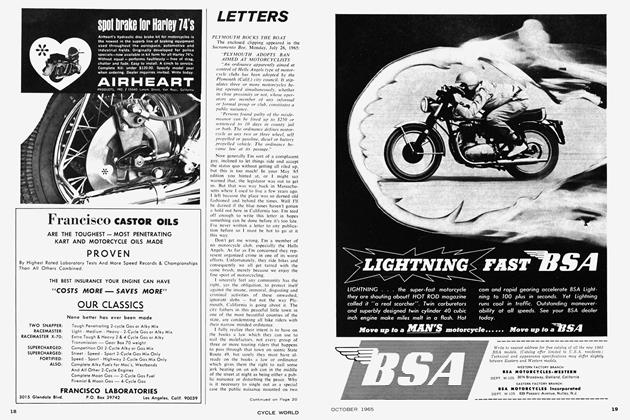

SOMETHING THERE IS about a BMW that sets it apart from the others — it doesn't handle the best, nor is it the fastest, hut in its quiet, imperturbable way it exudes the aura that here is the very best. Like a Rolls Royce it is smooth, seems to run forever, and it has a finely finished look that lasts and lasts and lasts. Today, without a doubt, the BMW is the machine that has the reputation all over the world for finest quality of design, materials and workmanship. It is a uniquely distinctive machine with its oppose twin engine, shaft drive, and unusual swinging-arm suspensions both front and rear.

And vet, if this is such a great motorcycle, why are there not more BMWs sec~ on the road? The price may have some thing to do with it, for quality seldom comes cheap. But that is not entirely it, as many, many experienced motorcyclists have no desire whatsoever to own a BMW. Maybe it is that gentlemen - gentlemen who also happen to like bikes - make the best 13MW owners. For a BMW, like a gentleman, has fine manners.

The 13~l\V owner is usually a proud nian - proud that he owns 1/ic prestigeous machine of motorcycling. He also appre ciates good engineering: not the kind of engineering that has double overhead cams, 10000 revs and road racing brakes, hut rather the good engineering that makes a bike as quiet as an owl in flight, as clean and vibration-free as an electric motor, as comfortable as a living room chair, and that will run for 100,000 miles and still be alive to serve more.

The story of the Bavarian Motor Works goes back many years to 1883 when a boy was born in Wurttemberg. Germany to the family of Fritz. Young Fritz later became Dr. lug. Max Fritz, a mechanical genius who helped start the BFW airplane engine manufacturing concern in 1916. In 1912 Dr. Fritz had designed the first successful small aircraft engine used in Germany, and in 1916 his company was called upon to serve the Kaiser's army by designing and producing airplane engines for the war effort.

After the war the company began producing a motorcycle engine that was used in the Victoria machine during 1921-22. The engine was a side-valve 5()0cc job that produced 6.3 hp at 3000 rpm.

It was in 1923 that the actual BMW company came into existence with Dr. Fritz as its chief designer, manager and president. Dr. Fritz worked in this capacity until the end of World War II, then continued on as a technical advisor. One of the first projects was the designing and building of a complete motorcycle, and to this end the infant company dedicated itself with Teutonic skill.

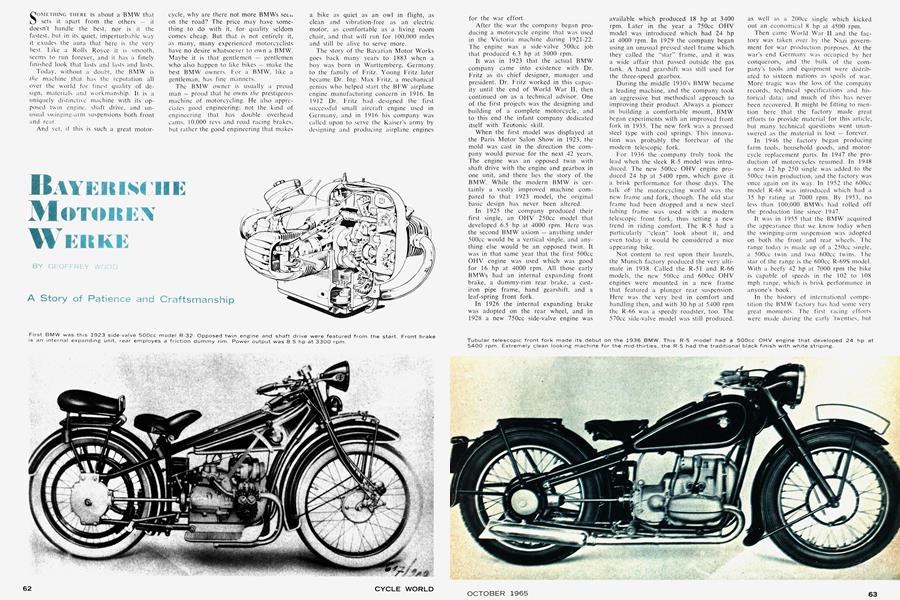

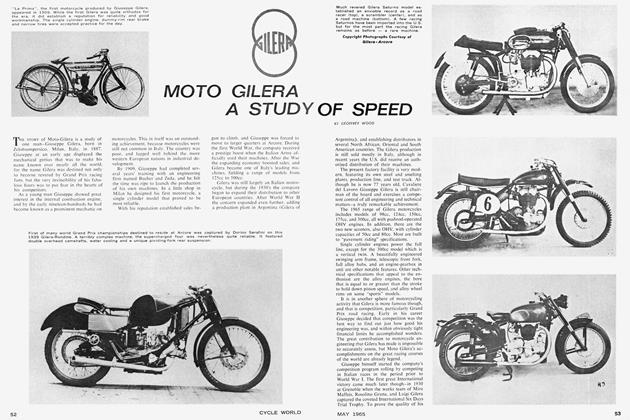

When the first model was displayed at the Paris Motor Salon Show in 1923, the mold was cast in the direction the company would pursue for the next 42 years. The engine was an opposed twin with shaft drive with the engine and gearbox in one unit, and there lies the story of the BMW. While the modern BMW is certainly a vastly improved machine compared to that 1923 model, the original basic design has never been altered.

In 1925 the company produced their first single, an OHV 250cc model that developed 6.5 hp at 4000 rpm. Here was the second BMW axiom — anything under 500cc would be a vertical single, and anything else would be an opposed twin. It was in that same year that the first 500cc OHV engine was used which was good for 16 hp at 4000 rpm. All those early BMWs had an internal expanding front brake, a dummy-rim rear brake, a castiron pipe frame, hand gearshift, and a leaf-spring front fork.

In 1926 the internal expanding brake was adopted on the rear wheel, and in 1928 a new 750cc side-valve engine was available which produced 18 hp at 3400 rpm. Later in the year a 750cc OHV model was introduced which had 24 hp at 4000 rpm. In 1929 the company began using an unusual pressed steel frame which they called the “star” frame, and it was a wide affair that passed outside the gas tank. A hand gearshift was still used for the three-speed gearbox.

During the middle 1930’s BMW became a leading machine, and the company took an aggressive but methodical approach to improving their product. Always a pioneer in building a comfortable mount, BMW began experiments with an improved front fork in 1935. The new fork was a pressed steel type with coil springs. This innovation was probably the forebear of the modern telescopic fork.

For 1936 the company truly took the lead when the sleek R-5 model was introduced. The new 500cc OHV engine produced 24 hp at 5400 rpm, which gave it a brisk performance for those days. The talk of the motorcycling world was the new frame and fork, though. The old star frame had been dropped and a new steel tubing frame was used with a modern telescopic front fork, thus setting a new trend in riding comfort. The R-5 had a particularly “clean” look about it, and even today it would be considered a nice appearing bike.

Not content to rest upon their laurels, the Munich factory produced the very ultimate in 1938. Called the R-51 and R-66 models, the new 500cc and 600cc OHV engines were mounted in a new frame that featured a plunger rear suspension. Here was the very best in comfort and handling then, and with 30 hp at 5400 rpm the R-66 was a speedy roadster, too. The 570cc side-valve model was still produced. as well as a 200cc single which kicked out an economical 8 hp at 4500 rpm.

Then came World War II and the factory was taken over by the Nazi government for war production purposes. At the war’s end Germany was occupied by her conquerors, and the bulk of the company’s tools and equipment were distributed to sixteen nations as spoils of war. More tragic was the loss of the company records, technical specifications and historical data; and much of this has never been recovered. It might be fitting to mention here that the factory made great efforts to provide material for this article, but many technical questions went unanswered as the material is lost — forever.

In 1946 the factory began producing farm tools, household goods, and motorcycle replacement parts. In 1947 the production of motorcycles resumed. In 1948 a new 12 hp 250 single was added to the 500cc twin production, and the factory was once again on its way. In 1952 the 600cc model R-68 was introduced which had a 35 hp rating at 7000 rpm. By 1953, no less than 100,000 BMWs had rolled off the production line since 1947.

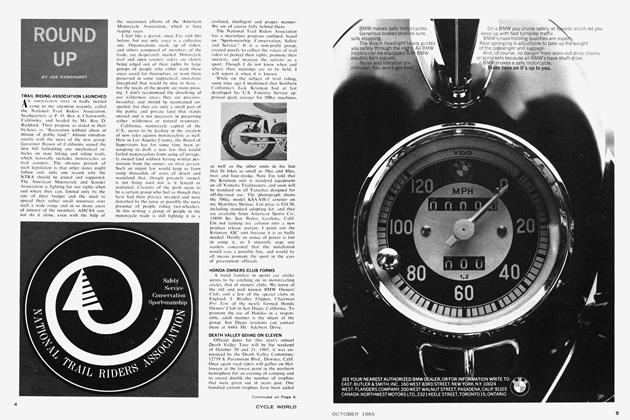

It was in 1955 that the BMW acquired the appearance that we know today when the swinging-arm suspension was adopted on both the front and rear wheels. The range today is made up of a 250cc single, a 500cc twin and two 600cc twins. I he star of the range is the 600cc R-69S model. With a beefy 42 hp at 7000 rpm the bike is capable of speeds in the 102 to 108 mph range, which is brisk performance in anyone’s book.

In the history of international competition the BMW factory has had some very great moments. 'I he first racing efforts were made during the early ’twenties, but it was not until sales reached goodly proportions during the early 'thirties that the company could afford a serious racing program. Always faithful lo their opposed twin-shaft drive layout, the BMW successes are a tribute to years of patient development that were not always strewn with roses.

It was during the early 1930's that intensive work began on a 500cc Grand Prix machine, and, as the rules then allowed it, a supercharger was used. In

1936 the world first received notice of what was to follow, when works riders Otto I.ey and Karl Gall carried off the last race of the season in Sweden by trouncing World Champion Jim Guthrie (Norton) rather badly.

I cy's BMW averaged 91.8 mph on the fast Swedish course, and there lies the crux of BMW’s problem to ascend to the Senior Class racing throne. Fast as they were, the bikes just were not the best handling or most readable on the circuits, and on the curves and corners they were getting carved up badly by the Nortons and Velocettes. It was only on a fast course with few sharp corners that their fierce performance advantage could offset the superior roadholding of their unsupercharged British competitors.

Methodically, the GP machine was developed. The rigid frame gave way in

1937 to a plunger rear suspension. The BMW had been plagued during the ’36 season with torque reaction from the drive shaft layout. Previously, twisting up the wick on the blown twin had created some disastrous effects when heeled over in cornering. The factory started the year by sending Jock West to the Isle of Man for the Senior TT, and fifth place was the best he could win. More work was needed.

The next race was the Dutch TT, and the trophy went to Munich after Jim Guthrie's Norton retired from the race with mechanical troubles. Then, in the Swiss and Belgian events, Guthrie showed the world that he still was champion by soundly trouncing the field. The next race was the home country Grand Prix on the Hohenstein-Frnstthal circuit, and Karl Gall and Otto Ley captured the prize for the fatherland. It was rather a hollowvictory. as Jim Guthrie was leading the race only one mile from the finish when he crashed and died later from his injuries.

I he balance of the season was a mixed picture. BMW with Jock West took the Ulster Grand Prix; BMW also took the Swedish again; Velocette won the French, and Gilera the Italian. So 1937 ended with the Munich concern winning four out of nine classic races, Norton still champion, and the BMW was still at a disadvantage on all but the fastest courses. During the long winter many problems would have to be sorted out in Munich.

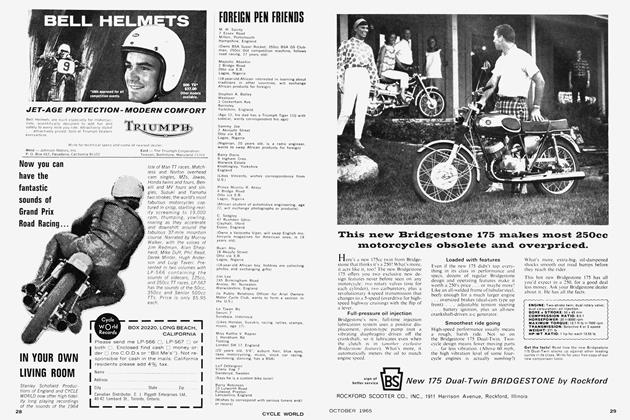

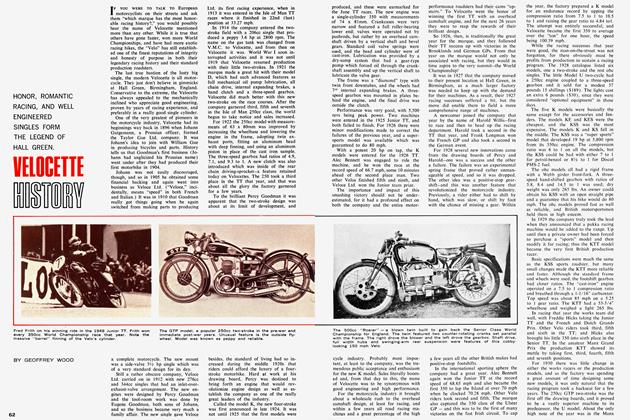

In the spring of 1938 the new contender came out of the race shop, and here was truly a magnificent racing machine. Rear plunger suspension was retained, but the girder front folk was replaced with a telescopic to improve road holding. Braking power was greatly increased with two full-width hubs, cast in alloy, which provided stopping power to match the speed. The vane-type Zoller compressor was still used, and the engines were producing no less than 78 hp at 8000 rpm on petrolbenzol fuel. The engine, incidentally, had a bevel gear and tower shaft drive to the overhead camshafts and ignition was bymagneto. The gearbox had four speeds.

The season started off poorly in the Isle of Man. Gall crashed in practice, the brilliant newcomer Georg Meier had a spark plug stripped out just before the start of the race and Jock West came home fifth, over three miles per hour behind the Norton of Harold Daniell. The next race was on the fast Belgian course, and Meier and West took first and third. Things were looking up.

The Swiss classic was held on the slow tortuous Geneva circuit that year, and once again it was Norton first and second. On to the Dutch 'IT and the tables were reversed — BMW first and second with Meier picking up another eight points toward the title. Back to Germany for the Grand Prix d’ Furope, and Meier once again pushed the Nortons of Harold Danicll and Fred Frith into 2nd and 3rd.

For the Ulster GP the factory sent over only Jock West, but that was all it took to win the event at the record speed of 93.98 mph — the highest speed ever recorded in a Grand Prix race. The last race of the season was at Monza, Italy, and BMWs scored a convincing one-two again with Meier taking the trophy. The season’s total was five out of seven races, with Georg Meier the World Champion. Only one race remained to be won — the TT!

In June of 1939 the factory sent their works team to the Isle of Man full of confidence. Their splendid twins had been clocked at 145 mph during the 1938 season. and Georg Meier had developed into a truly great rider. During the very first practice lap Karl Gall crashed and was killed, but Meier and West came through to lead the practice times by wide margins.

In the TT itself Meier rode a magnificent race with steady consistent cornering, and then scorching down the straight stretches nearly 20 mph faster than the Nortons and Velocettes. The result was a record speed, and to this date that 1939 event is the only Senior IT that BMW has ever won. Just for the record let’s list the leader hoard:

The balance of the 1939 season was less rewarding, as the Italian Gilera-Rondine supercharged four was faster than the Munich twins. Then Meier crashed in the Swedish event and was unable to ride the balance of the season, and so the championship was lost.

After the war, Germany was on "probation" and could not compete in international racing until 1952. The racing spirit was kept alive on homeland courses though, such as the 1950 Rheyit Circuit race where Meier used the pre-war compressor model to average a fantastic 129.87 mph, with a record lap of 134.21.

In 1953 a new BMW, the 500cc Rennsports, made its debut as both a works and production racer. With the post-war ban on supercharging, the new racer had normally aspirated tuin carburetors. A new frame was also adopted, which had swinging-arm suspension both front and rear.

While the post-war BMW success in Senior Class racing has not been nearly as good as during the pre-war days, Walter Zeller did garner a great number of second through sixth places in World Championship racing from 1953 through 1957. An experimental fuel injection system was used on Zeller’s machine, but the speed just wasn’t sufficient to stay with the Italian fours. In recent years the factory has not supported a works team.

If the post-war solo successes have not been too great, then the sidecar championships must certainly make up for it. For every year since 1954 the BMW has taken the sidecar title, and the flat twin with its low center of gravity is a natural for this class. There is nothing in sight that appears to be any threat either, as the fatherland moves toward its twelfth straight title in 1965.

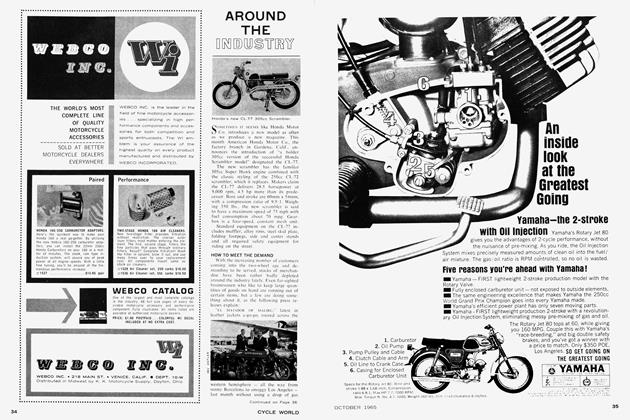

There is another facet of competition where the Bavarian concern has prominently figured, and this is the world of absolute speed. They first hit the news in 1929 when Frnst Henne took the World's Fastest title at 134.75 mph for the kilometer. His bike featured a 750cc pushrod OHV engine with a Zoller compressor.

Henne lost his title, and then gained it back at 137.86 in 1930. Again his crown was taken, and again he took it back at 151.76 in 1932. He then pushed it up to 159.0 in 1935. still using the 750cc engine.

Henne startled the world in 1936 with his 168.9 mph clocking, and that record was set with only a 500cc OHC road racing engine. The bike had a complete shell for the record attempt, which was probably the first successful use of full streamlining. During 1937 the title was again lost, and so, late in the year, Henne rolled out on the Frankfurt Autobahn and recorded 173.88 mph. That record stood for fourteen years.

Today the BMW still holds the official World Sidecar speed mark at 174.0 mph, plus a great number of long distance sidecar speed records. Willi Noll is the man who wears the crown, and his mark was set in 1955 with a 5()0cc engine. Florian Camathias also holds the standing start kilometer record for sidecars with an 88.38 mhp average.

And so this is the story of the Bayerische Motoren Werke — never any panic or quick decisions. Like making a fine German cheese, it takes time, and the end product will always be good. It can be said that BMW has never produced a poor motorcycle, and few there are that can make that claim.

Today work goes on to improve the breed. .A special works model for the International Six Days Trial has been built that is nearly 80 pounds lighter than the standard machine. A new frame, standard telescopic front fork and swingingarm suspension are used, and the engine has some minor modifications to pep up the performance. Don't expect to see it in the showroom soon, though, for it takes time to fully test at BMW. Time is something they seem to have lot of at Munich — slow but sure is their motto. •