TIME & DESIGN

Wraith for the long run?

CRAIG VETTER

Editor’s Note: We asked Craig Vetter, Obi-Wan of American motorcycle design, for his views on today’s V-Twin customs in general and the Confederate Wraith concept bike in specific. As usual with Vetter, we got more than we expected.

I love motorcycles and I love design. I especially appreciate designs that look good for a long time. What vehicles fall into this category? To name a few: 1932 Ford Model A Coupe, 1942 Lockheed Constellation airliner, 1965-70 Triumph Bonneville, the 1969 Easy Rider Captain America chopper, 1994 Britten V1000,1992 Lexus SC400 and 19942001 Dodge pickups. These things looked good when they were created; they look good today. If form follows function, then surely one of the functions of good design must be to look good for a long time.

I count Hariey-Davidsons among the good. There’s a lot of 1936 Knucklehead in the 2004 Heritage Softail. That’s a 68-year run! Isn’t this extraordinary? I cannot think of any motorcycle, car or airplane that has lasted this long. Some designers get it right early on and others are smart enough to leave it alone.

Unfortunately, most designers (or their bosses) don’t believe that good design should transcend time. They want us to tire of the old product so we will buy a newly designed “better” version. Today, the comment, “Sure is different,” is used by most people as some kind of compliment. The fact is, if a design looks new and exciting today, it will look old and tired tomorrow. You can quote me on this.

I have never wanted my work to look “new,” just “good.” My Triumph Hurricane, designed in 1969, and my Windjammer fairing, designed in 1971, looked good then and, if you’ll allow me, they look good today.

Fortunately, Harley has stayed with pretty much the same design all this time. But back in the ’60s and ’70s, although some of us may have secretly liked their looks, we could never trust their quality and were rightly suspicious of their reliability. Harleys got no respect, being produced essentially with 1940s tractor technology. The Japanese had spoiled us.

Two things happened in the mid-1980s that changed our perception of The Motor Company. One they had control over; the other they did not. The Evolution engine makeover brought Harley into the modern world. It retained H-D’s traditional look and actually exhibited some mechanical excellence. Evos became reliable transportation. For the first time in a long time, Milwaukee began paying attention to detail.

But the biggest factor? As baby-boomer American males reached 40, Harleys began to look irresistibly good. Nobody saw this coming. Suddenly, the classic American design—VTwin engine, fat tires, teardrop gas tank-just seemed “right.” In 1982,1 bought my first Harley. Soon, so did everybody else. You know the rest of the story. For the next decade and beyond, Harley continually increased production in a futile attempt to keep up with demand. For some popular models, buyers were required to plunk down a deposit 18 months in advance!

In the aftermarket, another part of the story was playing out. Over the Big Twin’s lifespan, a huge industry had sprung up making replacement components, including complete Evolookalike motors. When Harley could not supply enough bikes, it didn’t take the aftermarket long to realize that if they could produce engine and tranny cases, they could produce complete motorcycles. This “Age of the Clones” began around 1990.

Some simply built copies of the Softail, but others went the custom route with stretched frames, ever-fatter rear tires, 100-inch (and more!) motors, wild paint, lots of chrome. As the millennium approached, though, many of these clone-makers went out of business, victims of Harley’s increased production or their own poor build-quality. In their place, a new development in custom motorcycles was coming of age: the “coachbuilt chopper.”

Curiously, history is repeating itself here. In the 1920s, the Duesenberg Brothers boasted that they built the biggest, fastest, most expensive cars you could buy. Hollywood-types quickly became big supporters. Having a Duesenberg said, “Look at me. I have money to burn,” at least until the stockmarket crash of 1929.

Could this ever happen with motorcycles? Could owning the “right” motorcycle ever become a statement of social position? In the late 70s, I designed the Mystery Ship, a streetlegal roadracer, based upon serious AMA Superbike running gear. I wanted it to be the best of the best. It turned out to be the wrong thing at the wrong time. I built only 10.

Twenty years later, however, it is finally happening, based around the venerable Harley. Celebrities now find themselves attracted to the biggest, baddest, most flamboyant “look-atme” motorcycles.

Television sees this situation as entertainment for the rest of us. Couch potatoes everywhere can watch big, bad, pottytalking Harley guys building these things. It all takes on the trappings of professional wrestling.

But is this good design or just different design? The Vetter Design Statement offers a clue: “Anything that looks new and exciting today will look old and tired tomorrow.”

Most of these customs have been stretched and otherwise exaggerated to make sure you look at them. Their form follows this function. Most are not good design. You will yawn at them tomorrow. A quick test of this is to log onto eBay Motors and type in the name of your favorite custom-bike builder. You will be shocked at how little his creations are worth.

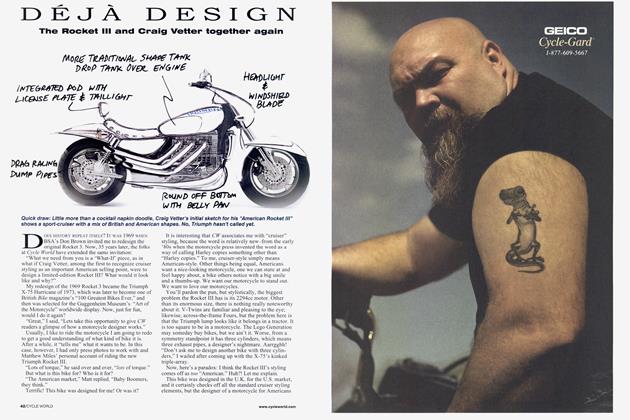

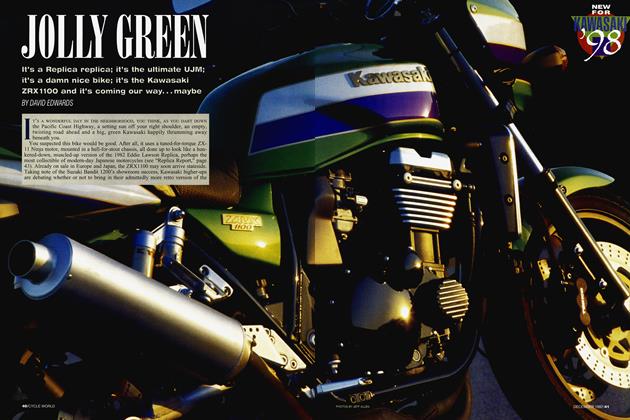

What about the Wraith? Designer J.T. Nesbitt shows some real innovation while having fun incorporating Vincent and Brough elements. The main tube and rear shock arrangement looks strong and simple, like my childhood tricycle (that’s me in the snapshot, taking my brother for a ride in 1946). The massive aluminum tube fitting into steel sockets is just one of many clever details. Okay, to my eye the new/old girder front end is too heavy-looking. And with no lights, no muffler, no mirrors, no license plate, no evap canisters, etc. (all the legally required parts that are hard to incorporate into a design), you could not ride this thing on the street. With those parts in place, the Wraith will take on a very different look.

As is, the Wraith mockup seems to be more of a conversation piece than a motorcycle. Is it classic design? No, not yet. Can the Wraith be the pivotal inspiration that blazes a long-needed new direction for customs? The frame is brilliant. The front end is fixable. The bike has real possibilities.

The big question is: Will it be around for another 68 years? As they say, time will tell.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

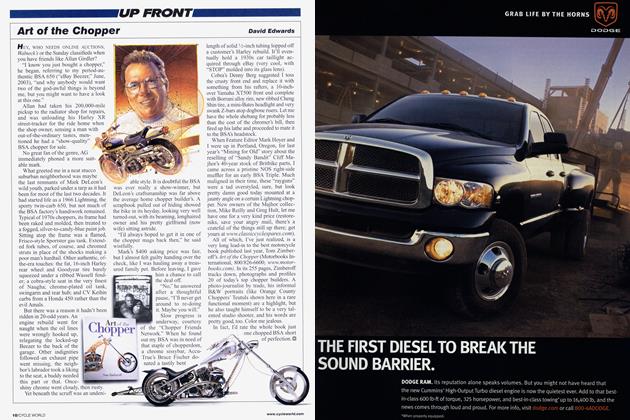

Up FrontArt of the Chopper

April 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Age of Tough Engines

April 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCCutting It Close

April 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2004 -

Roundup

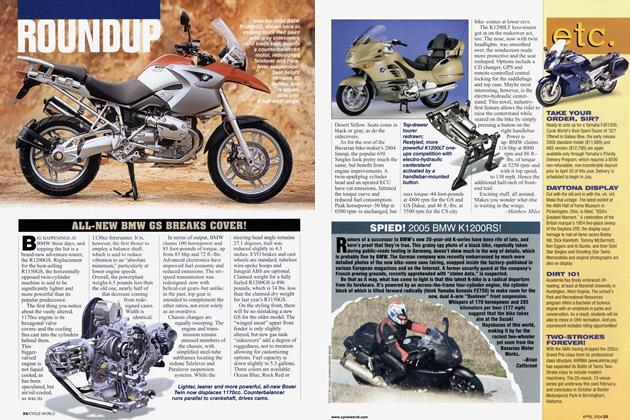

RoundupAll-New Bmw Gs Breaks Cover!

April 2004 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

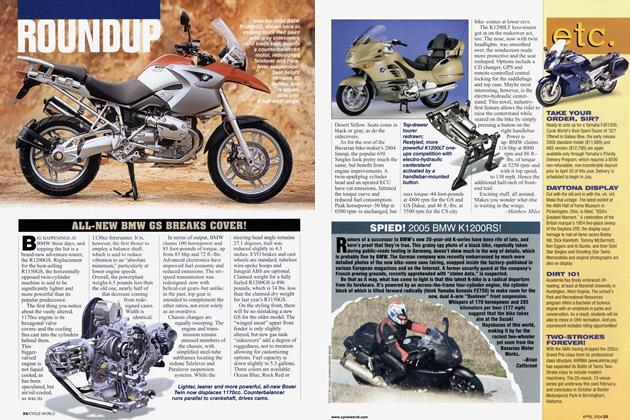

RoundupSpied! 2005 Bmw K1200rs!

April 2004 By Brian Catterson