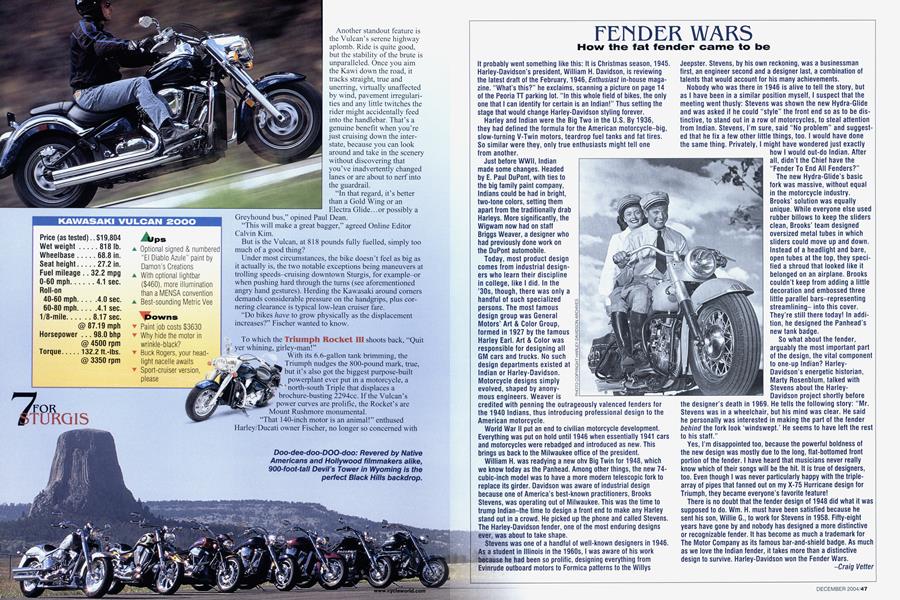

How the fat fender came to be

FENDER WARS

Craig Vetter

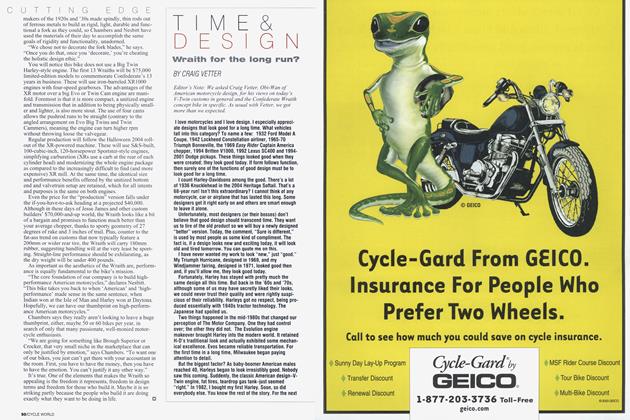

It probably went something like this: It is Christmas season, 1945. Harley-Davidson's president, William H. Davidson, is reviewing the latest draft of the February, 1946, Enthusiast in-house magazine. "What's this?" he exclaims, scanning a picture on page 14 of the Peoria IT parking lot. "In this whole field of bikes, the only one that I can identify for certain is an Indian!" Thus setting the stage that would change Harley-Davidson styling forever.

Harley and Indian were the Big Two in the U.S. By 1936, they had defined the formula for the American motorcycle-big, slow-turning V-Twin motors, teardrop fuel tanks and tat tires. So similar were they, only true enthusiasts might tell one from another.

Just before WWII, Indian made some changes. Headed by E. Paul DuPont, with ties to the big family paint company, Indians could be had in bright, two-tone colors, setting them apart from the traditionally drab Harleys. More significantly, the Wigwam now had on staff Briggs Weaver, a designer who had previously done work on the DuPont automobile.

Today, most product design comes from industrial design ers who learn their discipline in college, like I did. In the `30s, though, there was only a handful of such specialized persons. The most famous design group was General Motors' Art & Color Group, formed in 1927 by the famous Harley Earl. Art & Color was responsible for designing all GM cars and trucks. No such design departments existed at Indian or Harley-Davidson.

Motorcycle designs simply evolved, shaped by anony mous engineers. Weaver is credited with penning the outrageously valenced fenders for the 1940 Indians, thus introducing professional design to the American motorcycle.

World War II put an end to civilian motorcycle development. Everything was put on hold until 1946 when essentially 1941 cars and motorcycles were rebadged and introduced as new. This brings us back to the Milwaukee office of the president.

William H. was readying a new ohv Big Twin for 1948, which we know today as the Panhead. Among other things, the new 74cubic-inch model was to have a more modern telescopic fork to replace its girder. Davidson was aware of industrial design because one of America's best-known practitioners, Brooks Stevens, was operating out of Milwaukee. This was the time to trump Indian-the time to design a front end to make any Harley stand out in a crowd. He picked up the phone and called Stevens. The Harley-Davidson fender, one of the most enduring designs ever, was about to take shape.

was one of a handful of well-known designers in 1946. nt in Illinois in the 1960s, I was aware of his work e had been so prolific, designing everything from rude outboard motors to Formica patterns to the Willys Jeepster. Stevens, by his own reckoning, was a businessman first, an engineer second and a designer last, a combination of talents that would account for his many achievements.

Nobody who was there in 1946 is alive to tell the story, but as I have been in a similar position myself, I suspect that the meeting went thusly: Stevens was shown the new Hydra-Glide and was asked if he could "style" the front end so as to be dis tinctive, to stand out in a row of motorcycles, to steal attention from Indian. Stevens, I'm sure, said "No problem" and suggest ed that he fix a few other little things, too. I would have done the same thing. Privately, I might have wondered just exactly

how I would out-do Indian. After all, didn't the Chief have the "Fender To End All Fenders?"

The new Hydra-Glide's basic fork was massive, without equal in the motorcycle industry. Brooks' solution was equally unique. While everyone else used rubber billows to keep the sliders clean, Brooks' team designed oversized metal tubes in which sliders could move up and down. Instead of a headlight and bare, open tubes at the top, they speci fied a shroud that looked like it belonged on an airplane. Brooks couldn't keep from adding a little decoration and embossed three little parallel bars-representing streamlininginto this cover. They're still there today! In addi tion, he designed the Panhead's new tank badge.

So what about the tenaer, arguably the most important part of the design, the vital component to one-up Indian? HarleyDavidson's energetic historian, Marty Rosenblum, talked with Stevens about the Harley Davidson nroiect shortly before the designer's death in 1969. He tells the following story: "Mr. Stevens was in a wheelchair, but his mind was clear. He said he personally was interested in making the part of the fender behind the fork look `windswept.' He seems to have left the rest to his staff."

Yes, I'm disappointed too, because the powerful boldness of the new design was mostly due to the long, flat-bottomed front portion of the fender. I have heard that musicians never really know which of their songs will be the hit. It is true of designers, too. Even though I was never particularly happy with the triple array of pipes that tanned out on my X-75 Hurricane design for Triumph, they became everyone's tavotite feature!

There is no doubt that the fender design of 1948 did what it was supposed to do. Wm. H. must have been satisfied because he sent his son, Willie G., to work for Stevens in 1958. Fifty-eight years have gone by and nobody has designed a more distinctive or recognizable fender. It has become as much a trademark for The Motor Company as its famous bar-and-shield badge. As much as we love the Indian fender, it takes more than a distinctive design to survive. Harley-Davidson won the Fender Wars.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

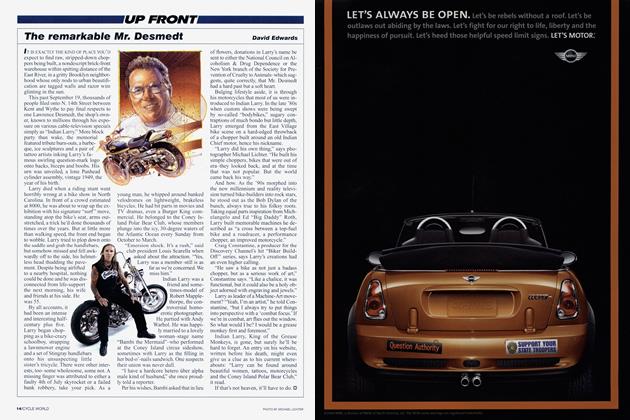

ColumnsThe Remarkable Mr. Desmedt

December 2004 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsA Minor Odyssey

December 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

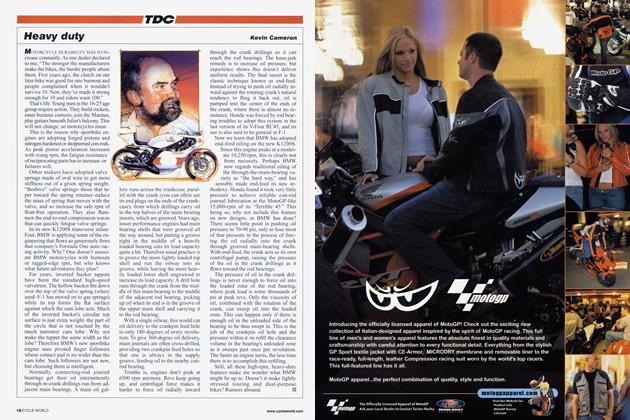

TDCHeavy Duty

December 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2004 -

Roundup

RoundupAll-New Suzuki Gsx-R1000!

December 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupMoto-Street Suzuki

December 2004 By Mark Hoyer