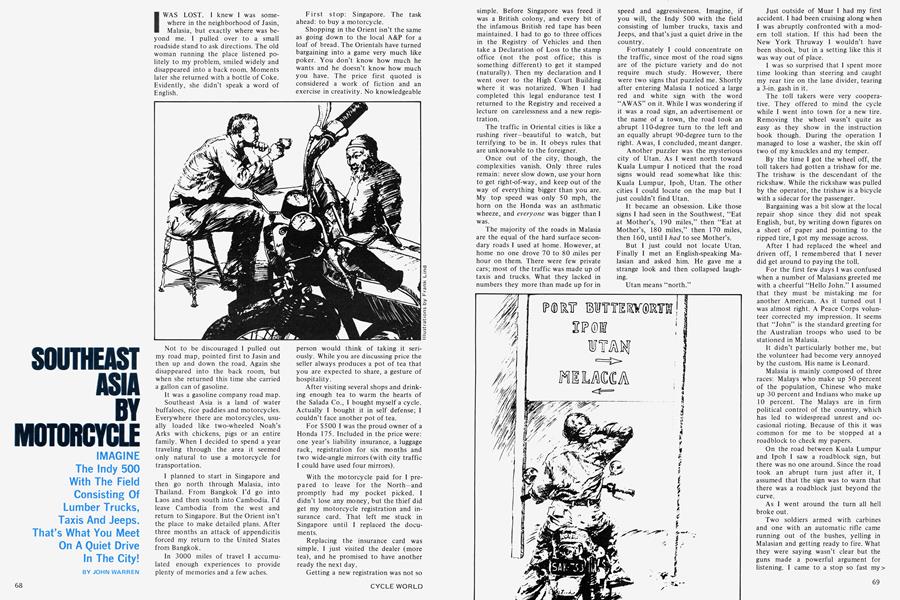

SOUTHEAST ASIA BY MOTORCYCLE

IMAGINE The Indy 500 With The Field Consisting Of Lumber Trucks, Taxis And Jeeps. That's What You Meet On A Quiet Drive In The City!

JOHN WARREN

I WAS LOST. I knew I was somewhere in the neighborhood of Jasin, Malasia, but exactly where was beyond me. 1 pulled over to a small roadside stand to ask directions. The old woman running the place listened politely to my problem, smiled widely and disappeared into a back room. Moments later she returned with a bottle of Coke. Evidently, she didn't speak a word of English.

Not to be discouraged I pulled out my road map, pointed first to Jasin and then up and down the road. Again she disappeared into the back room, but when she returned this time she carried a gallon can of gasoline.

It was a gasoline company road map.

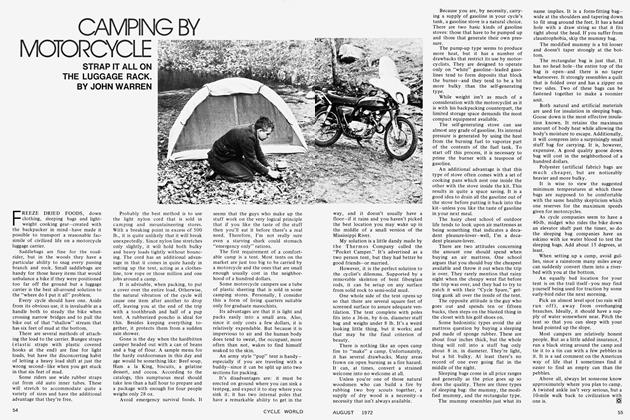

Southeast Asia is a land of water buffaloes, rice paddies and motorcycles. Everywhere there are motorcycles, usually loaded like two-wheeled Noah’s Arks with chickens, pigs or an entire family. When I decided to spend a year traveling through the area it seemed only natural to use a motorcycle for transportation.

I planned to start in Singapore and then go north through Malasia, into Thailand. From Bangkok I’d go into Laos and then south into Cambodia. I’d leave Cambodia from the west and return to Singapore. But the Orient isn’t the place to make detailed plans. After three months an attack of appendicitis forced my return to the United States from Bangkok.

In 3000 miles of travel I accumulated enough experiences to provide plenty of memories and a few aches. First stop: Singapore. The task

ahead: to buy a motorcycle.

Shopping in the Orient isn’t the same as going down to the local A&P for a loaf of bread. The Orientals have turned bargaining into a game very much like poker. You don’t know how much he wants and he doesn’t know how much you have. The price first quoted is considered a work of fiction and an exercise in creativity. No knowledgeable person would think of taking it seriously. While you are discussing price the seller always produces a pot of tea that you are expected to share, a gesture of hospitality.

After visiting several shops and drinking enough tea to warm the hearts of the Salada Co., I bought myself a cycle. Actually I bought it in self defense; I couldn’t face another pot of tea.

For $500 I was the proud owner of a Honda 175. Included in the price were: one year’s liability insurance, a luggage rack, registration for six months and two wide-angle mirrors (with city traffic I could have used four mirrors).

With the motorcycle paid for I prepared to leave for the North—and promptly had my pocket picked. I didn’t lose any money, but the thief did get my motorcycle registration and insurance card. That left me stuck in Singapore until I replaced the documents.

Replacing the insurance card was simple. I just visited the dealer (more tea), and he promised to have another ready the next day.

Getting a new registration was not so simple. Before Singapore was freed it was a British colony, and every bit of the infamous British red tape has been maintained. I had to go to three offices in the Registry of Vehicles and then take a Declaration of Loss to the stamp office (not the post office; this is something different) to get it stamped (naturally). Then my declaration and I went over to the High Court Building where it was notarized. When I had completed this legal endurance test I returned to the Registry and received a lecture on carelessness and a new registration.

The traffic in Oriental cities is like a rushing river—beautiful to watch, but terrifying to be in. It obeys rules that are unknowable to the foreigner.

Once out of the city, though, the complexities vanish. Only three rules remain: never slow down, use your horn to get right-of-way, and keep out of the way of everything bigger than you are. My top speed was only 50 mph, the horn on the Honda was an asthmatic wheeze, and everyone was bigger than I was.

The majority of the roads in Malasia are the equal of the hard surface secondary roads I used at home. However, at home no one drove 70 to 80 miles per hour on them. There were few private cars; most of the traffic was made up of taxis and trucks. What they lacked in numbers they more than made up for in speed and aggressiveness. Imagine, if you will, the Indy 500 with the field consisting of lumber trucks, taxis and Jeeps, and that’s just a quiet drive in the country.

Fortunately I could concentrate on the traffic, since most of the road signs are of the picture variety and do not require much study. However, there were two signs that puzzled me. Shortly after entering Malasia I noticed a large red and white sign with the word “AWAS” on it. While I was wondering if it was a road sign, an advertisement or the name of a town, the road took an abrupt 110-degree turn to the left and an equally abrupt 90-degree turn to the right. Awas, I concluded, meant danger.

Another puzzler was the mysterious city of Utan. As I went north toward Kuala Lumpur I noticed that the road signs would read somewhat like this: Kuala Lumpur, Ipoh, Utan. The other cities I could locate on the map but I just couldn’t find Utan.

It became an obsession. Like those signs I had seen in the Southwest, “Eat at Mother’s, 190 miles,” then “Eat at Mother’s, 180 miles,” then 170 miles, then 160, until I had to see Mother’s.

But I just could not locate Utan. Finally I met an English-speaking Malasian and asked him. He gave me a strange look and then collapsed laughing.

Utan means “north.”

Just outside of Muar I had my first accident. I had been cruising along when I was abruptly confronted with a modern toll station. If this had been the New York Thruway I wouldn’t have been shook, but in a setting like this it was way out of place.

I was so surprised that I spent more time looking than steering and caught my rear tire on the lane divider, tearing a 3-in. gash in it.

The toll takers were very cooperative. They offered to mind the cycle while I went into town for a new tire. Removing the wheel wasn’t quite as easy as they show in the instruction book though. During the operation I managed to lose a washer, the skin off two of my knuckles and my temper.

By the time I got the wheel off, the toll takers had gotten a trishaw for me. The trishaw is the descendant of the rickshaw. While the rickshaw was pulled by the operator, the trishaw is a bicycle with a sidecar for the passenger.

Bargaining was a bit slow at the local repair shop since they did not speak English, but, by writing down figures on a sheet of paper and pointing to the ripped tire, I got my message across.

After I had replaced the wheel and driven off, I remembered that I never did get around to paying the toll.

For the first few days I was confused when a number of Malasians greeted me with a cheerful “Hello John.” I assumed that they must be mistaking me for another American. As it turned out I was almost right. A Peace Corps volunteer corrected my impression. It seems that “John” is the standard greeting for the Australian troops who used to be stationed in Malasia.

It didn’t particularly bother me, but the volunteer had become very annoyed by the custom. His name is Leonard.

Malasia is mainly composed of three races: Malays who make up 50 percent of the population, Chinese who make up 30 percent and Indians who make up 10 percent. The Malays are in firm political control of the country, which has led to widespread unrest and occasional rioting. Because of this it was common for me to be stopped at a roadblock to check my papers.

On the road between Kuala Lumpur and Ipoh I saw a roadblock sign, but there was no one around. Since the road took an abrupt turn just after it, I assumed that the sign was to warn that there was a roadblock just beyond the curve.

As I went around the turn all hell broke out.

Two soldiers armed with carbines and one with an automatic rifle came running out of the bushes, yelling in Malasian and getting ready to fire. What they were saying wasn’t clear but the guns made a powerful argument for listening. I came to a stop so fast my> sunglasses flew off.

Evidently it had been a boring time of day and these upright guardians of their country had elected to take a snooze in the shade by the side of the road. Once they had identified me as an American they returned to their interrupted siesta.

Another contact with government forces in Malasia was less violent but even more frightening. I was having supper with a group of Chinese students, and the discussion had ranged over the political situation in Malasia. When it got late I rose to excuse myself but one of the group stopped me. “Don’t leave yet,” he said and pointed at a group of militia lounging against the wall. “If you leave they will arrest us for talking to you.” After another hour the militia got bored and wandered down the street. When I returned to my hotel I asked the desk clerk if what I had been told was true.

He pointed to a small box on the front page of the “Straits Times” that announced that 10 rumor mongers had been arrested yesterday right in this city. “If you say anything that does not agree with the official policy of the government you can be arrested. You were lucky —not long ago the police would have arrested everyone in the group and had you deported,” he said.

That put quite a kink in my conversations from then on.

Learning I was just roaming, a Malasian friend suggested that I visit the Cameron Highlands, an area in the mountains about 50 miles north of Kuala Lumpur that is the vacation area for middle-class Malasian families. It’s

over 5000 ft. above sea level, giving it a much cooler climate than the rest of the country, and, according to the guide book, “The Highlands are reached by a scenic highway winding upward through lush forest.” That was an understatement.

The road between the main highway and the Highlands is 30 miles of the worst curves I’ve ever seen. The road looks like it was laid out by a snake with the DTs and a sadistic sense of humor. Despite the scenery, my attention was riveted on the road itself as it curved, dipped and climbed up the side of the mountain. To add interest to the game, trucks loaded with rocks would come charging downhill at odd intervals and try to catch me on their side of the road-“their side” being defined as anything left of the right shoulder.

After 20 miles of this I was ready to throw in the towel. I pulled over to the widest shoulder I could find and stretched out on the grass.

The Highlands Uphill Slalom must have taken more out of me than I realized since I fell asleep almost instantly. I woke up only about 10 min. later and I wasn’t alone. From my vantage point on the ground he looked a shade over 10 ft. tall, dressed in worn pants and carrying the biggest, longest spear I had ever seen.

I was told later that it was a dualpurpose spear and blow gun. Fortunately, I didn’t know it at the time. I was scared enough.

I recognized the gentleman from a picture in the National Museum. He was a member of an aboriginal tribe: “They are friendly and colorful but they have numerous taboos that the stranger must be careful not to violate.” He looked colorful all right, but not too friendly. I didn’t think that I’d violated any taboos but I thought I’d better say something friendly. All I could think of was “Hi.”

He said nothing.

I said, “Selmat Detang” (Malay for Hi).

He said nothing.

I said, “By.”

Same answer.

Desiring to be elsewhere (anywhere),

I mounted the cycle and kicked over the engine into a roaring silence. Another kick, no go.

Five kicks later I observed that a Honda runs better if the ignition key is turned on. I rejoined the Malasian Rollercoaster, leaving my .new acquaintance standing by the side of the road.

After a night of dreaming about an endless winding road I set out to explore the Cameron Highlands. The rubber plantations of the lowlands are replaced by terraced fields growing vegetables and tea. Everywhere there is an inch of space someone has dug a terrace until the hills resemble a series of giant steps. It was such an interesting view I didn’t give the road the attention it demanded.

When a little boy ran into the road I swerved to the right. Unfortunately, that space was taken up by a truck coming the other way, and I had to go left. At this point the kid complicated things by falling flat on his face.

Things began happening very fast. I left the road to avoid the boy, the cycle came to an abrupt stop in knee-deep mud and I came to a somewhat delayed stop about 10 ft. beyond that. My camera landed about 3 ft. beyond me. However there wasn’t any mud there— just air. About 75 ft. of it. This just had to be the one place in the Highlands where they didn’t build terraces. Scratch one camera.

The kid? He disappeared before I picked myself up. I never set eyes on him again.

Mount Brinchang at 6666 ft. above sea level is the highest point that can be reached by motor vehicle in Malasia. For the first three miles the road to it was in good condition and the grade was gradual enough so I could stay in third gear. After the third mile things began to get interesting. At several points the road was so washed out I couldn’t see how an auto could get through; the surface of the road was so covered with washed down gravel that I couldn’t tell if it was still paved. It seemed that the grade was getting steeper, but it wasn’t too easy to judge with all my attention on keeping the cycle on the road and keeping me on the cycle.

After a half-dozen ages ançl five more miles I reached the top. I had a magnificent view of the radio tower on the peak and the surrounding scenery, for the first hundred yards or so.

One of those picturesque fluffy clouds had perched itself right on the top of the mountain and showed absolutely no inclination to go elsewhere. Two hours later all I could see was the transmitter tower and a hell of a lot of cloud. I fired up the Honda and headed down the road.

The grade had not seemed this steep coming up and it seemed to be getting steeper by the second. Finally, I had both my front and rear brakes on, the transmission in low and I was zigzagging to kill speed.

Ahead I saw a sign that I had missed on the way up. It said “Danger, Steep Hill Ahead.” Why me Lord? Why me?

Actually the hill didn’t get any steeper. It couldn’t without being called a cliff. By the time I got to the bottom I was covered with sweat and it was a cool day.

When I returned to the hotel the room clerk approached me and said, “If you plan to climb Mount Brinchang I want to warn you that the road is dangerous and you should not try it alone.” Now, that’s timing.

Chickens are one of the staples in the Malasian and Thai diet. They are everywhere, in the roads, in the villages and sometimes even in the trees. “Nasi Ayam” or rice with chicken is one of the favorite dishes of this area. But shortly after I arrived in Malasia I was in a roadside restaurant and forgot the Malasian word for chicken. Try as I might all I could remember was “nasi” (rice). When it’s a choice between dignity and food there really is no choice. I said, “nasi,” stuck my hands into my armpits, flapped my elbows and clucked!

Everyone was hysterical. One of the waiters ran out, got the cook and motioned for me to repeat my act. Several people were drawn off the street by the noise and each new arrival called for a command performance.

Finally I got my dinner for 30 cents and the price of my dignity.

In Thailand a chicken that crossed the road got me a village full of friends. I had been cruising at about 40 mph through a series of gently rolling hills when a chicken ran into the road ahead of me, and with no time for evasive action, the result was one dead chicken. Realizing that the bird might have represented a sizable investment for a family I swung the cycle around. Before I could get the 50 yd. back to the scene it seemed that the whole village had gathered.

I had been in similar situations back in the States so I took out my wallet and prepared to be taken. Since no one in the group could speak English, they indicated that I should wait. It was well worth the wait. She was about 5 ft. tall, weighed about a hundred pounds and looked like a delicate native doll. She explained that she had learned English in Chula University in Bangkok.

When I brought up the fact that I had killed the chicken, but was willing to make restitution, she conferred with the farmer for a moment and said, “It was very old and would have died very soon. You owe us nothing, but we would like you to stay for a meal.” Although they had invited me to dinner it was actually a question and answer session about the United States.

“You drive a Japanese motorcycle. Doesn’t America make any?”

“Is it true that all Americans live in palaces?”

“Are you married?” An all-time favorite.

“Have you ever met an astronaut?” Asians are fascinated by the space program, and during the Apollo 13 flight it was a topic of conversation everywhere I went.

And on and on and on.

The meal was delicious-chicken, of course.

In Bangkok the lightening struck. A severe stomach was diagnosed as appendicitis, and after a stay at St. Louis Hospital, the doctor told me that motorcycling was out for at least a month. That ended the adventure, but not the problems.

When I entered Thailand I signed a $500 reexport guarantee. If I left the country without taking the motorcycle with me I would owe the government of Thailand $500 smackers.

It was a cinch that the airline wasn’t going to accept a Honda 175 as hand luggage, so that left only one choice. While I took the high road the Honda took the low road. I put it on a freighter bound for San Francisco.