"HICKS"

Ben Hands

What Is Part Publisher, Part Pamphleteer, Part Promoter, Part Un-promoter, Part Hip, Part Establishment, Part AMA, Part Thornbush, Part Back Country New England, Part International, Part Plain Likeable, And All Motorcycling?

Over the past 20 years Bob Hicks’ name has become synonymous with competitive motorcycling in New England.

In this part of the country, competition means dirt riding—predominantly scrambles, motocross, enduros and lately, observed trials. Flattracking is gone now, and although New England still hosts the annual Loudon bash, most of those riders are from elsewhere.

Hicks has had a hand in all the major dirt events and continues to be a leading promoter of all types of motorcycling; he is probably the single most important figure in New England motorcycle sport. During the Fifties, Hicks spent several years at Northeastern University near his home in Wenham, before turning to electronic engineering with a company that makes radar components. During this period his interest in motorcycles switched from road bikes to flattrackers, with which he admits only moderate success.

Bob soon switched jobs (to publishing Cycle Sport) and events (to scrambles and enduros). He scrambled Greeves, Bultaco, CZ and H-D Sprints under familiar No. 5, currently carried by his son, Ricky. Nearly 500 races and almost as many trophies later, Bob again changed his preference to enduros. One gets the impression at first that he regards enduros as more of a pleasant diversion than serious competition, since he does not ride hard and occasionally goes two-up, carrying his wife, Jane. This impression is only partially correct, however, for he has garnered a place on the United States ISDT entry in 1969 and 1970, winning a Bronze on the first outing and a Silver on the second.

Much of Hicks’ prominence in New England competition has come from his promotional efforts. One of the founders of the New England Sports Committee, he almost singlehandedly organized and ran the famous annual Grafton scramble. This two-day event was extraordinarily popular with spectators, as well as competitors, but it ultimately died because of a bad press.

By this time however, Bob had founded Intersport, which promotes the highly successful Pepperell motocross events. Intersport has also developed the annual Berkshire Trial, a two-day, 400-rider event, which has become one of the “qualifiers” for aspirants to ISDT competition. The latter event represents a logistic and public relations masterpiece, since the course covers over 400 miles, largely on private land. Hicks assists Al Eames for months, choosing new routes and contacting all the landowners and local police along the route.

Casual trail riding and checking routes for events like the Berkshire have made , Hicks one of the few real trail experts in the Northeast. He currently is establishing a network of bike trails which is now concentrated in Massachusetts, and which he hopes will eventually cover New England.

This kind of expertise has led groups like horsemen, traditional arch-enemies of motorcyclists, to call on Hicks to lay out routes for their extended trail rides. He is also a member of the Advisory Committee of the White Mountain National Forest, where he must advise on the recreational activities of all types of forest users.

The AMA has been another of Bob’s major concerns, and he has spent a tremendous amount of time and effort trying to effect what he sees as essential reforms. Hicks has gone well beyond editorial attacks on the AMA by becoming a trustee and a member of the Association’s Executive Board. Currently his efforts are directed mostly elsewhere, but he still maintains an industry-level membership and aims an occasional Cycle Sport editorial at the AMA.

Bob’s interest in motorcycles is more than 20 years old, but his involvement didn’t really become total until the creation of the New England Sports Committee in 1958. It soon became obvious that some sort of communications medium was necessary to publicize the Committee’s competition activities and to ease relations between the various motorcycle clubs which did most of the promoting in those days, but which often more closely resembled warring tribes than promotors.

As a Sports Committee member, Bob agreed to publish a newsletter, but he did it on his own, doing the work himself and using his own money. By 1959 the newsletter had become so popular that Bob quit his engineering job to devote full time to it.

Within a year he had gone deeply in debt and was forced to return to the engineering job, but only a year later he quit again and has been publishing full time ever since.

The newsletter, now a full fledged magazine, Cycle Sport, has grown to a circulation of 5000 and is widely recognized as the authority on local events up and down the East Coast. Bob explains that the magazine has also provided him with a much-needed soapbox from which he can expound his strong ideas on most subjects relevant to motorcycling.

More recently Hicks has begun a second magazine, New England Trail Rider, which is devoted to trail riding, enduros, and trials, while Cycle Sport concentrates on street riding, scrambles, motocross and occasional reports of road races. Trail Rider, after IV2 years of publication, has about one-half the circulation of Cycle Sport and is growing rapidly. It is another soapbox, if somewhat smaller, and Bob uses this one primarily to make known his ideas on land use and trail systems while simultaneously berating cyclists and manufacturers for public offenses like excessive noise.

This compendium of accomplishments in competition promotion and journalism is as much a reflection of Hicks’ personality as it is of his hard work and total involvement. Bob is passionately devoted to motorcycling, but he maintains an enviable perspective and openmindedness. There is virtually no issue pertaining to motorcycling on which he does not have a strong opinion, but, at the same time, he has retained the ability to listen, evaluate and either reject conflicting arguments or modify his own accordingly. He has achieved a rare.balance between aggressiveness and reason which makes him an unusually capable individual.

About an hour’s drive to Wenham from Boston through the surrounding commuter/bedroom communities brought us to the Hicks’ home, a modest old frame house just beyond a large development. We found Bob in his shop out back repairing some of the bends and dings his machine suffered while front-running the Berkshire. The shop and a spacious second floor office for the magazine are the remains of the family barn and chicken coop, although Bob had to point this out before we could see it. Bob himself is a healthy six feet, with hair which has changed from a burr to shoulder length over the last five or 10 years. He appears to be in excellent physical condition although he claims a 40-percent hearing loss on one side from scrambling a super-noisy Greeves.

After locating Bob and the house, I ran into town for breakfast and on the way had a discussion of Bob’s possible age with my fickle girl friend, who found him extraordinarily handsome. She maintained that he cannot be past his early 30s, while I (desperately) argued that he’s pushing 40. On our return we went straight to the heart of the question.

Q. How old are you, Bob?

A. Forty-one. Fooled you didn’t I?

To reach 41, he’s come a long way. Started road riding in 1950, then tried flat track, enduros and was promoting his own scrambles by 1954. He and a partner had opened a Triumph and BSA shop in 1953, essentially to support their own racing. His publication was the same type of operation—a hobby that turned into a living.

Birth Of A Soapbox

Q. How did that start?

A. In 1958 we formed the New England Sports Committee to coordinate the clubs who were doing most of the promoting. I felt it was essential that we have communication because the clubs always sat in their respective clubhouses around New England hating each other and wondering if another club was trying to steal their race date. Cycle Sport started as a mimeographed newsletter to the clubs. We didn’t have to like each other, but if everybody would work together I thought we’d all profit.

Q. And?

A. Of course we did. The sport has quintupled since 1958.

Q. The magazine is more than a newsletter now.

A. Yes. Pretty soon people began to say I should publish race results and some pictures. So I used my own money to print 500 copies of an eight-page magazine and sent them to every scrambler, dealer and club that I knew, soliciting advertising and subscriptions. At the end of 1959 I quit my job and spent all of 1960 working to build the magazine up. But I went so deeply in debt that I had to go back to work for a year. In 1961 I quit my job and I haven’t worked for anybody else since. In the last few years we have finally gotten to the point where we don’t have to get big bank loans to get through the winter because nobody pays their bills then.

Q. Did you have any idea where you were going when you started this business?

A. Nope. My whole life is that way. That’s one of the greatest things about it. 1 get up every morning and look forward to going to work. What’s going to happen today? I don’t know where I’ll end up.

Q. Then you think publishing is fun?

A. If it wasn’t fun I wouldn’t do it. It’s been 1 1 years since I worked for anybody else and it’s been lovely. No matter how benevolent an employer is you still feel that you’ve been had. I don’t feel that way.

Q. What kind of magazine is Cycle Sport?

A. It’s always been an insider’s book; an outsider wouldn’t understand it. People buy it because they want to find out what’s going on in non-professional competition.

Q. How big is it?

A. About 5000 circulation, but I’m beginning to refer to it as “that other magazine.” Cycle Sport is the bread and butter, but Trail Rider is where I’m at right now. My personal involvement has moved.

Q. What is New England Trail Rider about?

A. It’s an inspirational book for the guy who digs trail riding: how to go, how to play and all that neat stuff. But it’s also a communications effort between us and the other people who use the trails. The book isn’t a whitewash job on the sport; you can’t really call it propaganda, but I am trying to present our case.

Q. What’s its circulation?

A. About 2500. I haven’t made any big efforts to promote it. But the important aspect of Trail Rider’s circulation is that there are about 100 people who aren’t motorcyclists that get it. Conservationists, land management people and private land owners—the movers and shakers in this business of land use.

Q. What’s Trail Rider's future?

A. I have a creepy feeling that it’s going to evolve into a New England trails magazine. This is not a calculated thing, but a lot of people who are getting the book and aren’t bikies are really digging it.

Q. You use your magazines for a lot of editorializing, too.

A. I say what I think, let the chips fall where they may. I’ve been outspoken over the years, especially about the AMA and industry, criticizing basically the same people who are advertising in my publication.

Q. Does that present problems?

A. I’m beholden to the motorcycle sport and industry to the extent that our interests are essentially the same; we want to promote the best interests of the sport. I am not beholden to any individual industries whose advertising I solicit and who support my publication. I fault them for their shortcomings, including the equipment they foist off on the public sometimes, but I’ve lost very few advertisers as a result. They’re men enough to accept what I say. They don’t call me up and hint I’ll lose advertising because they know it won’t make any damn difference to me.

Q. Is that because you’re not a big magazine?

A. I don’t think so. I don’t reach a lot of people but, happily, I do reach the people who make things happen.

Q. What’s your policy about other people’s opinions?

A. If somebody takes the trouble to write or call me and the guy is obviously sincere, I’ll put it in the book, regardless of how much I disagree with him. Editorially, of course, I assume my own position, but I don’t try to put people down in the letters column because the editor always has the last word.

Q. It sounds like a pretty good position to be in.

A. My publishing is still a fun thing. I enjoy about as much freedom as it is possible to have in our society.

A Salvo Against The Industry

Q. What are your gripes against industry?

A. The Industry Council [MIC] is made of representatives of the motorcycle industry and most of them are secondechelon types; they’re not the number one men in their firms. They’re mainly concerned with their jobs, their careers and the goal of the business. So none of them will go out on a limb for anything and none of them wants to do anything that will embarrass any of the other members, because it might come home to roost someday. There’s very little argument; they strive for consensus and the only way you can get a unanimous agreement is to decide to not do anything because that’s safe; nothing will happen.

The industry is aware of its problems. They’ve got a land use committee, but they’re not yet willing to spend any money. They’re just talking about things. If you put up a billboard that says, “Don’t litter the desert,” it won’t solve the problem. Or if you print up a brochure and give it to everybody who buys a trail bike, this is good but it’s a pretty half-hearted step. The industry hasn’t really faced up to its responsibilities in saturating the land with bikes and not worrying about the consequences until it begins to hurt like it is in California.

The industry will sit and talk, but they will always fail to act. They spend all their time hiring people to mind the store and put out a new brochure or new billboard campaign, but won’t hire anybody who knows anything—they’re scared of them.

A Philosophy Of Riding

Q. What kind of riding do you do?

A. Last year I did 3500 miles of trail riding. I enjoy indulging myself in what I’m good at: trail riding. I can ride with anybody, but I can’t bring myself to compete with them. It’s just a lot of fun.

I like to ride a bike in the woods because it puts wheels on my feet; it’s just like walking but I can cover so much ground that I can get a feel of the geography of an area that I could never get walking. So for me riding a bike through the woods is like looking over a topographical map. The hiker indulges in knowing the flora and fauna and that whole scene that I’m not into at all— which is why I don’t mind riding on powerlines. I don’t give a damn that aesthetically they look terrible; I get a feel for hills and dales, rivers and streams and soils.

Q. I have a feeling that motorcyclingespecially trail riding-is one of the sports most sensitive to population pressures.

A. Do you think so?

Q. Yes, because our demands are for a non-essential need-even though it’s extremely important to 10 percent or so-and because demands for space are becoming very heavy.

A. I don’t know. Many of the sports that are feeling the pressures of population are participant sports like golf that require an expensive and concentrated facility. Now you have to go out at 6 a.m. and wait for your turn at the tee. Good Lord, right around here in this densely populated suburban area there’s land that’s not being used for anything. Right now we are 18 miles from Boston in part of the megalopolis that stretches to Washington, D.C., and yet I could take you out and we could do 60 or 70 miles of trail riding and never get more than 20 miles from this house.

Q. Then you think that this sport is one of the least sensitive to population pressures?

A. It can fit in anywhere as long as you avoid the obvious abuses. The trouble is that too many people buy bikes and they overload the same places. Anybody with a little imagination goes somewhere else.

What I’m trying to do now is to establish a lot of reservoirs where these new guys can go and they’ll be permitted and welcome. There’s a lot of places where I can go and I’m welcome, but 100 guys on a weekend wouldn’t be. So I want to set up these places where 100 guys can go. Then I can continue to go to so-and-so’s land who’s given permission but wouldn’t want all those other ding bats.

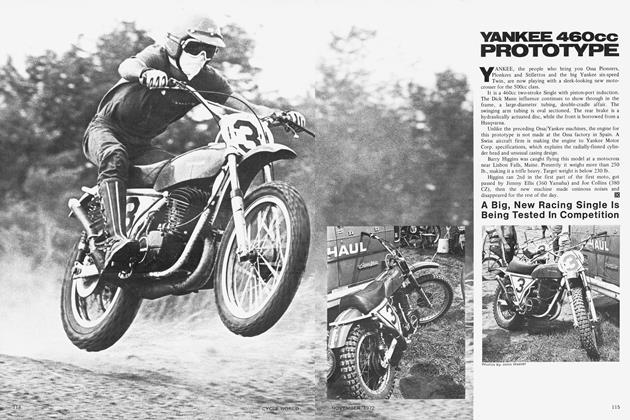

Q. What’s wrong with your bike now? (Bob’s bike is on a stand looking very muddy and vaguely bent. Its rear wheel is missing.)

A. Well, this is the result of the Berkshire. My job is to ride ahead on the course and make sure all the arrows are up so nobody gets lost. About 168 miles out on Saturday’s 200-mile ride my rear wheel bearing disintegrated. Al [Eames] was riding behind me, so when he came along I told him that he had the job for the last 30 miles. The bearing was gone and the wheel was riding on the brake shoe, so it kept heating up and locking. I didn’t want to sit around all afternoon and wait to be rescued, so I took some oil from my tank and soaked the brake lining, making the brakes enough of a wheel bearing so that I could ride carefully back to the finish.

Q. What is this bike anyway?

A. This bike has been with me for six years, and every year it’s new. It has a 500 Triumph engine, and that’s the only Triumph part on it. Dave Yetman built the frame, it has Betor forks from a Bultaco scrambler, it has a Honda swinging arm and muffler, an Ossa front wheel, a Yamaha seat and rear fender, Cheney rear wheel, a Webco oil tank and a gas tank from Rocky’s Cycle. But it’s not always been this way—I change it all the time. It’s my life’s work. That motorcycle has 500 hours of my labor in it to make it the way I want it. To somebody else it’s just another grungv black bike, but to me it’s the ultimate manifestation of my thinking and feeling on how a bike should feel and handle in the woods.

(Hicks discovers that the spigot on his swinging arm chain oiler is broken so the swinging arm must be removed.)

Ach! I hate to work on that kind of thing. I love to design and develop and improve it, but I hate to do all the grubby maintenance.

Q. Is this the best bike you’ve ever had? A. I love this machine because it’s part of me, and it’s my whole life, but it isn’t the bike I would ride in serious competition.

Q. Why wouldn’t you use it in the ISDT, for instance?

A. It does weigh 300 lb.-but mostly because it’s set up more like your family car than a racing car. It’s not finicky, it’s inoffensive, quiet, it will idle while you bang up arrows or cut a tree out of the way. It rides effortlessly in third or fourth gear, even in the woods, and when you go out and start it in the morning you can be confident of getting through the day. But when you go into competition like the Six Day, it’s just too much machine, so I rode the Ossa, which is a lovely motorcycle.

Q. You rode in the last two ISDT’s didn’t you?

A. Yes, in 1969 an Ossa was shipped over to Germany from here, and in 1970, in Spain, it came right from the Barcelona factory.

Q. How was it?

A. I had very good rides both times. The bikes were very reliable and it was nice to go twice in my life and finish both times. I got a Bronze medal the first time and a Silver last year. And that’s it—when people say, “now it’s time for a Gold,” I say, “Man, I’m 41 years old and I’m not up to that gold medal stuff. I’ve had a good time and I’m going to end on a happy note.” I don’t have any competitive desire in bike races any more. I love to ride and I enjoy going fast when I’m in the mood, but I can’t get fired up.

Q. But isn’t that what enduros are ab out - being consistent rather than fast?

A. No. You’ve still got to be competitive, and concentrate. About two-thirds of the way through an enduro I begin to get serious. (Bob’s wife interjects, “That’s why he takes me.”)

Q. That seems inconsistent with your success in the ISDT.

A. The satisfaction of the Six Day was proving to myself that if the involvement was of major proportion, I could still bring myself to try. That’s an increasing problem as you get older.

Q. Isn’t it really that you’re just trying something else these days?

A. Well—yes. I’m deeper into mental and emotional things than the physical involvement.

A Philosophy Of Competition

Q. How was this year’s Berkshire?

A. Good. It rained all day on the second day just like last year, but we finished about 100 out of 412 starters, compared to about 45 finishers last year. It was a demonstration that the general ability of the riders is considerably improved.

Q. Why was that a good event?

A. I don’t believe an event that knocks out all but 10 percent is good. You hear about national events with eight guys out of 800 finishing. That is a very poorly planned event.

Q. What’s a good event then?

A. One that weeds out the incompetents and the unprepared. Anybody that’s reasonably competent and well-prepared should be able to finish. No novices finished the Berkshire this year.

Q. Shouldn’t the real incompetents be eliminated before the event begins?

A. That’s what we did. We gave A and B riders preference and filled the field with C riders, none of whom finished. Al [Eames] says he can lay out a 200-mile ride all on dirt roads and we’d still lose half the field-the novices. Either they get stoked and do something foolish or they don’t know a chain link from a spark plug.

We haven’t decided, but we think that we’ll cut the field for next year’s Berkshire and restrict it to A and B riders.

Q. How would you describe the overall situation with enduros in New England? A. You get to a certain point in any sport when too many people want to play and there just isn’t room. If there’s a popular show in the city and you want to go, you’ve got to buy your tickets six months in advance; you can’t just go and say “here I am.” That’s what’s happening in scrambles and enduros. In scrambles it may be chaos, but it’s okay as long as there’s no distinct danger situation. But enduros that run over the public land and highways are different. We can’t have any things like California where 1500 guys turn out and maybe 200 of them are qualified enduro riders and the rest are semi-street riders.

Q. Was the requirement that riders go to school for an enduro license prompted by the numbers of riders, or by accidents?

A. Both. The two fatals that we had last year graphically illustrated the need for controlling access to enduros, because totally unqualified people were getting into them.

Q. Were the fatalities of the sort that schools could prevent?

A. Both boys were brand new and had never been in enduros. One was killed three-quarters of a mile from the start, still on pavement. He was going 70 mph when the bend tightened up and he went off the road. I subsequently learned that he thought it was a race and he was supposed to go like a bat out of hell to win.

Q. What’s involved in the schools?

A. The school is a day of showing riders how the game is played with a miniature enduro. When they show up at a real enduro they know what’s going to happen. It doesn’t guarantee they’ll be winners certainly, but dammit, when they’re sitting on a starting line they’ll know how the event’s run, how the scoring works, and they will have some grasp of what they’re getting into.

Q. How’s it working?

A. The New England Trail Rider Association formed [by Hicks] last spring got over 600 licensed riders by May 1.

Q. Why don’t more people object to having to go to school?

A. Fortunately, the license program, the Trail Rider Association and the schools are backed by guys who are well established and recognized experts. We have their support plus the support of all the organizers. We’re people who know the game; we’re not just power hungry.

Q. Does any of this apply to scrambles and motocross?

A. Yes. The sport has now reached a point where we’re saturated—supersaturated. We’ve got so many riders that we have to turn guys away.

Q. Why?

A. 350 guys show up at a scrambles and it’s chaos. It may be organized chaos if you know what you’re doing, but it’s still an interminable succession of racing events to process 350 guys through an afternoon of scrambling.

Q. Hasn’t your solution been to have simultaneous events at different locations?

A. Well, that would be nice, but the over-abundance of riders now makes it such a hassle to run a race that the average club says why bother. As the sport has grown riders have gotten an increasing amount of leverage on the clubs for rider benefits, so it’s costing more. Now they have to shell out $350 a day for first aid, where in bygone years, they didn’t even bother with it. So a lot of clubs, which are essentially social groups anyway, have given up promoting.

Q. What’s the answer then?

A. If five percent of the scramblers in New England would work together to run a series of monthly motocrosses they would have their own organization. If they didn’t like the way things were being done, they could change it. But it’s hard to get people off their butts, because all they want to do is show up and ride.

Q. How can you go on promoting the sport in your magazine, knowing that oversaturation is the result of increased popularity?

A. We’re going through a crisis stage. What we’ve got to do is promote the apparatus to handle riders.

Q. Can a magazine promote promoters? A. Yes. You just keep talking about successful events and people with outside money pop up. The problem is these people [outside promoters] seem to think there’s nothing to it, just a field with some fence in it and some two-bit clubs along with some jerk editor from upstairs in a chicken barn. They try and pick my brain. It’s an ego thing but if they really want to lean on me, they’ll have to pay for it. I’m tired of having people call me up and ask me to lay it all out for them. They seem to think they can step in here and in their very first effort in a totally new location duplicate the eighth annual Pepperell event. We’ve built that event since 1966 starting with a 2000 gate and reaching 12,000 last year. It’s been a steady annual increment that indicates to me that the people who came enjoyed it enough to pass the word on. We like to do it in an inconspicuous way and make it keep happening. We haven’t gone after the buck. We spent way more money than average to try and do it right and we end up making more money yet because people respond when you do things in the proper way.

(Continued on page 99)

Continued from page 39

"...And, For The Faint-Hearted

Q. So much for enduros and motocross. What do you think about trials?

A. Trials is a competition that the faint-hearted can get into-a guy who wants to compete but doesn’t want to get hurt. I don’t begrudge them their sport, but fellas, please don’t ask me to get enthused about it. They say that the pressure is just as great in a trials as for high point in an enduro, and I agree; emotionally it could very well be. But comparingscrambles to trials is like comparing lacrosse to chess, they’re both demanding, but in totally different ways; in lacrosse you’ll get your teeth knocked out, but in chess you just blow your mind. These trials guys damn near blow their minds. To me a motorcycle is to take me from here to there at some speed. So when you take an $800-900 machine that has a five-speed gearbox and you only use first or second and proceed at virtually a walking pace over something that can only be walked over anyway, it’s getting pretty refined. I don’t feel it’s utilizing the true potential of a motorcycle.

But I carry their news and they’re nice, sincere people who really like what they’re doing. It just doesn’t suit my tastes.

On The AMA, A Parting Shot

Q. I’m almost afraid to ask, but I want to hear your thoughts on the AMA.

A. I’ll spare you most of the details. Summing up the AMA—it’s an existing administrative organization that could be a huge benefit to motorcycling, but it suffers from a basic flaw; there’s no opportunity for those who participate in AMA activity to have any effect on overall policy. You and I, small as we are, have an opportunity to vote someone into office who may do things the way we like. Obviously, your individual impact is tiny, but ultimately the cumulative effect of you and a sufficient number of people who think the way you do can elect a senator or governor who will tend to reflect your feelings.

Well, the AMA with 100,000 members is so structured that those members have zero—I mean zero—voting power in policy making. That is totally in the hands of the motorcycle industry. The

(Continued on page 104)

Continued from page 104

enough to do the things they ought to. They are fence straddlers, do-nothings, whose automatic response to a controversial issue is to appoint a study committee that won’t do anything except bury it.

The industry argues that they are the only ones who are willing to put the time and money into these things, but actually the cumulative dues from all industry members is $1400 versus close to a million dollars from the Class A members. The only other industry expense is sending an employee to eight or 10 meetings a year—the entire administrative set-up of the AMA is paid for by income which is primarily the dues of the $7 members.

Q. Sounds like a rip-off.

A. It sure is, and I don’t dig it one bit—although there’s nothing criminal here—nobody’s lining their pockets.

Q. Are you a member of the AMA ?

A. Since 1950 I’ve been a Class A member and around 1959 I was a promoter and promoted many AMAsanctioned events in New England—but I won’t now because of my basic disagreement with the way they do things. For the last five years I’ve been a Class B [industry] member—one of the bad guys. As a publisher of a magazine I can be a trade member and get the reports of the meetings of the Executive Board, and I can get letters, reports and financial statements. At least I know what’s going on, which is more than the average member can ever find out. It doesn’t mean that I endorse their policies.

Q. How do you revolutionize the AMA? Asa trustee or with a legal action?

A. I’m an evolutionary, not a revolutionary. The AMA should start to bring the Class A membership into power. They formed the congress—which was a good idea—but they shouldn’t have rigged it. The next step is to elect delegates from each district. Now if an industry wants representation in there, let them have one delegate. If they’ve got a vested interest in the sport, they should have one, but why two? That’s to give them a majority if they need it-one is fair. I’m open-minded about it.

The Executive Board should disavow its veto powers over the congress, and the congress should elect from among its district delegates a certain percentage of the members of the Executive Board.

I feel that since district delegates, having no background, are obviously not experienced, they should be a minority of the Executive Board. Initially a 10-man executive board would have a couple of elected delegates and then, over a period of, say, six years, it would develop to a 5-5 split. This would allow the district delegates to continue to develop the ability needed to serve on the board.

(Continued on page 118)

Continued from page 112

Q. What have you done that’s evolutionary?

A. Last winter I introduced a resolution to the congress (which was unanimously endorsed) that the trustees of the AMA create a seat on the Executive Board for a member elected from the congress to have full voting powers in policy decisions. That’s just one man out of eight at that time. Instead they increased the board to 10, limited it to industry members and tossed out the resolution as unworkable and impracticable.

They also said the resolution went against the by-laws of the corporation. Well, of course it did! But the trustees can amend the by-laws by a two-thirds majority vote, and they have been amended a dozen times in the last four years that I’ve been there. But every amendment has been to further tighten the control of the industry on the AMA.

Q. It sounds like they are afraid of everybody.

A. Yes, you’re exactly right—they are afraid.

Q. If AMA were more responsive to riders and sportsmen, wouldn’t it do the industry more good, too?

A. Of course it would! But they’re afraid that the control of the sport will get into the hands of someone who isn’t selling motorcycles and these people will decide to do something that will restrict the sale of motorcycles.

You’re afraid of the dark when you’re a kid, because you don’t know any better. It’s the same way that the establishment today is afraid of the youthful radicals who are politically ineffectual but who keep making so much noise that it scares the establishment. They fear that if they let go of their control somebody will push them around. They’re an uneasy dictatorship-they won’t let go.

Q. One last question: We are in a weird time historically ; this country has a lot of had things going on. Do you see motorcycling in any particular relationship to any of these problems?

A. Nope. Motorcyclists cannot take themselves seriously enough to believe that they have any significant impact on the current social or political atmosphere.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

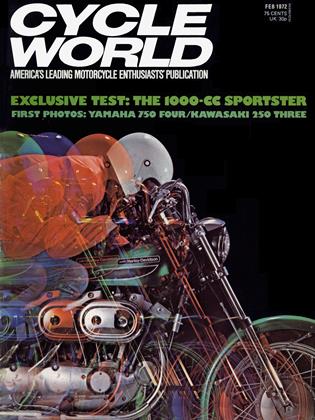

February 1972 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

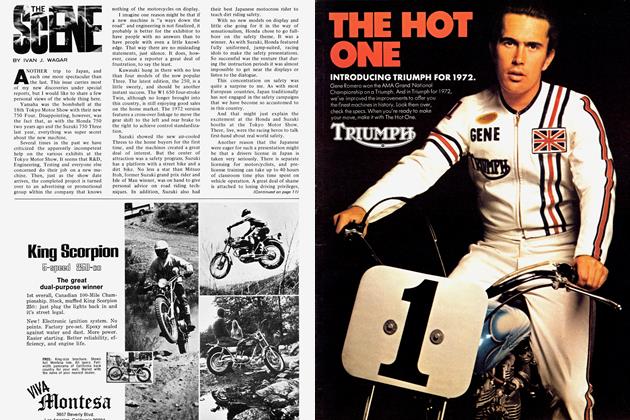

DepartmentsThe Scene

February 1972 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1972 -

Departments

Departments"Feedback"

February 1972 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

February 1972 By Jody Nicholas -

Previewed In Japan

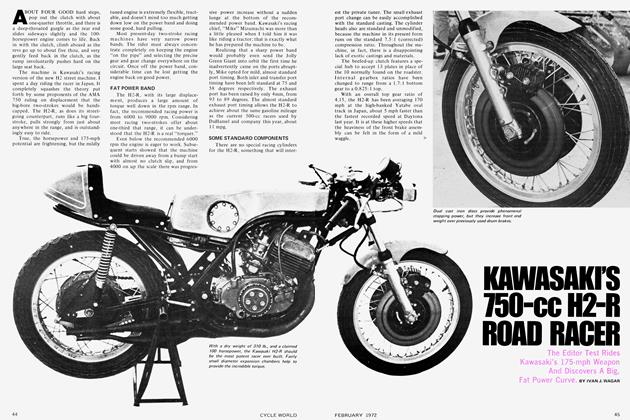

Previewed In JapanKawasaki's 750-Cc H2-R Road Racer

February 1972 By Ivan J. Wagar