CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

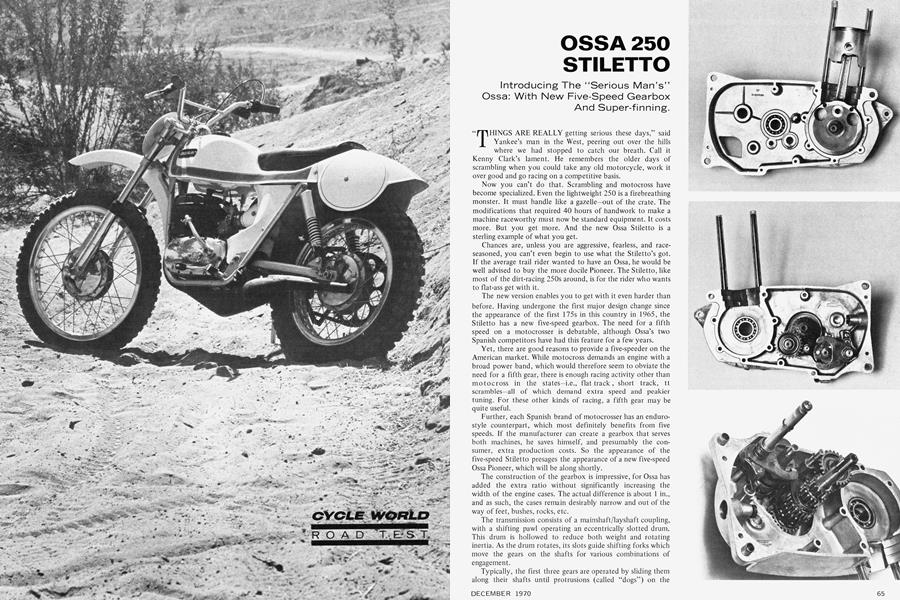

OSSA 250 STILETTO

Introducing The “Serious Man’s” Ossa: With New Five-Speed Gearbox And Super-finning.

“THINGS ARE REALLY getting serious these days,” said Yankee's man in the West, peering out over the hills where we had stopped to catch our breath. Call it Kenny Clark’s lament. He remembers the older days of scrambling when you could take any old motorcycle, work it over good and go racing on a competitive basis.

Now you can’t do that. Scrambling and motocross have become specialized. Even the lightweight 250 is a firebreathing monster. It must handle like a gazelle—out of the crate. The modifications that required 40 hours of handwork to make a machine raceworthy must now be standard equipment. It costs more. But you get more. And the new Ossa Stiletto is a sterling example of what you get.

Chances are, unless you are aggressive, fearless, and raceseasoned, you can’t even begin to use what the Stiletto’s got. If the average trail rider wanted to have an Ossa, he would be well advised to buy the more docile Pioneer. The Stiletto, like most of the dirt-racing 250s around, is for the rider who wants to flat-ass get with it.

The new version enables you to get with it even harder than before. Having undergone the first major design change since the appearance of the first 175s in this country in 1965, the Stiletto has a new five-speed gearbox. The need for a fifth speed on a motocrosser is debatable, although Ossa’s two Spanish competitors have had this feature for a few years.

Yet, there are good reasons to provide a five-speeder on the American market. While motocross demands an engine with a broad power band, which would therefore seem to obviate the need for a fifth gear, there is enough racing activity other than motocross in the states—i.e., flat track, short track, tt scrambles—all of which demand extra speed and peakier tuning. For these other kinds of racing, a fifth gear may be quite useful.

Further, each Spanish brand of motocrosser has an endurostyle counterpart, which most definitely benefits from five speeds. If the manufacturer can create a gearbox that serves both machines, he saves himself, and presumably the consumer, extra production costs. So the appearance of the five-speed Stiletto presages the appearance of a new five-speed Ossa Pioneer, which will be along shortly.

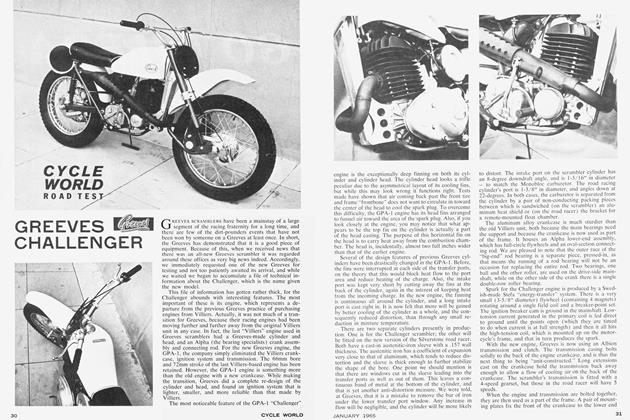

The construction of the gearbox is impressive, for Ossa has added the extra ratio without significantly increasing the width of the engine cases. The actual difference is about 1 in., and as such, the cases remain desirably narrow and out of the way of feet, bushes, rocks, etc.

The transmission consists of a mainshaft/layshaft coupling, with a shifting pawl operating an eccentrically slotted drum. This drum is hollowed to reduce both weight and rotating inertia. As the drum rotates, its slots guide shifting forks which move the gears on the shafts for various combinations of engagement.

Typically, the first three gears are operated by sliding them along their shafts until protrusions (called “dogs”) on the selected gear engage with corresponding slots in anotñer gear. Even on this conventional part of the gearbox there is a degree of racing sophistication in that the bases of the dogs are undercut slightly to encourage thorough engagement under load. Normally, the buyer would have to undertake this operation himself.

The novel aspect of the Ossa gearbox is that neither fourth nor fifth gear must slide along the mainshaft to be engaged; they are, in fact, fixed longitudinally on the mainshaft. Between them is an extremely lightweight slotted receiver, which slides toward the desired gear and meshes with it.

While sliding dogs are not a new idea, the Ossa’s slider is different in that the dogs are attached to the gears, rather than onto the sliding receiver. The receiver is therefore lighter and produces less inertia to resist the shifting and engagement action onto fourth and fifth gears, which, being more direct than the other gear combinations, are subject to heavy power loadings. The sliding dog receiver is also more compact than the traditional sliding dog, and in its own way contributes to making the entire gear assembly smaller. This, of course, will reflect on the overall size of the engine cases.

Even though the rider now has a somewhat narrower set of ratios to play with, Ossa has made no attempt to increase peak horsepower at the expense of losing the broad power band characteristic to the Stiletto. Port timing remains the same as on the previous model, as does the combustion chamber contour and piston shape. If anything, the slightly reshaped expansion chamber smooths power impulses and seems to make throttle response less sudden.

That formidably finned new barrel, equal in size to those gracing many a 500-class motocross engine, greatly increases the ability of the engine to cool itself. While this does not directly affect the nominal power output of the engine, it does have an indirect effect on power.

Ossa’s experiments conducted on standard motocross cylinder barrels revealed that an air-cooled, two-stroke engine, in 30 minutes of continuous hard running corresponding to the average motocross heat, can lose 30 percent of its power output. This is due to heat buildup. Practically speaking, such a power loss can spell disaster for a competitor toward the end of the race. So, in effect, the copious finning on the new Stiletto, by dissipating heat more effectively, serves to increase power output under critical racing conditions.

Along with the new barrel comes a larger cylinder head. In addition to the centrally located spark plug hole, there is another hole already tapped on the right side for the addition of a second spark plug, or a compression release. If both compression release and an extra spark plug are desired, space has been provided to the left of center to tap yet another hole to the combustion chamber.

In an effort to reduce retooling costs, Ossa has managed to preserve some commonality between the old and new designs. The left-hand case on the new 250 is the same as that on the previous model, and gasket sizes remain the same throughout.

While there are no basic changes in the conventional mild steel, arc-welded, double-cradle frame, some features of the suspension and running gear are new. The swinging arm pivots on nylon bushes instead of rubber. Aluminum is used for the triple clamps, and double bolts are used to grip the stanchions, thus spreading the load and increasing rigidity. The Betor telescopic forks have 7 in. of travel, and are equipped with lightweight aluminum sliders. The five-way rear shock absorbers are also Betor. A pin through the front axle bolt provides a handle for withdrawing it, facilitating wheel changes. While the brake size remains the same as before, the rear wheel hub has been redesigned; it has eight instead of six mounting holes for the chain sprocket. The space between the holes is scooped out, saving a small amount of weight. This last feature does not appear on our machine, which was rushed to California for testing and then air-mailed back to Yankee Motor Corp. in Schenectady, where it is being prepared for Barry Higgins to ride in the international motocross series.

We can predict that the rapid Mr. Higgins will have a good ride, as the new machine is well balanced, handles superbly in choppy terrain and is extremely flexible. The front end is rigid, and the geometry enables you to “steer” a tight course, rather than trying to second-guess where the front wheel is going to go in the next two seconds. Rear damping is effective, with only minimal wheel hop being elicited when braking hard on a bumpy downhill.

Seating position is comfortable, and the handlebars are wide enough to allow cutting down to taste. The notched folding footpegs are well placed and don’t protrude too far from the frame.

While the Stiletto can put as much horsepower on the ground as most people can tolerate, it can be cowtrailed, albeit somewhat aggressively. It can be lugged down quite low in the rpm range, which is rather surprising, for it was fitted with a cold (NGK B-10 E) racing plug during the full duration of the test.

Befitting the Stiletto’s special nature, it comes with a complete kit to make the competitor’s job easy. This includes owner’s manual, tool kit, three extra sizes of carburetor jets, 11-tooth and 13-tooth countershaft sprockets (a 12-tooth is standard) with spare lock washers, and a handy, detachable side stand that mounts over the footpegs.

The new Stiletto is a great bike to ride, and is attractively styled in white fiberglass. It costs more this year, but is worth every penny. Like the man says, it’s getting very serious.

OSSA 250 STILETTO

List Price $945

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

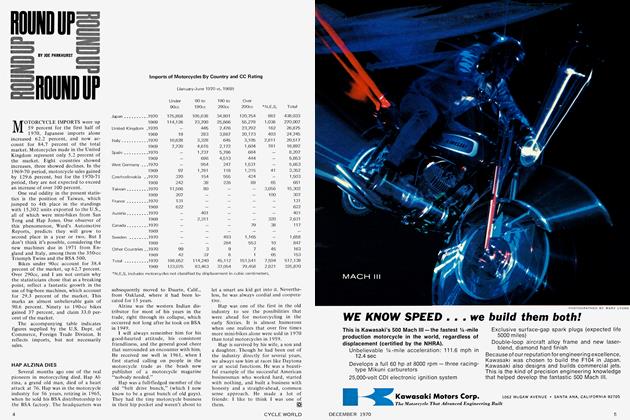

DepartmentsRound Up

December 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

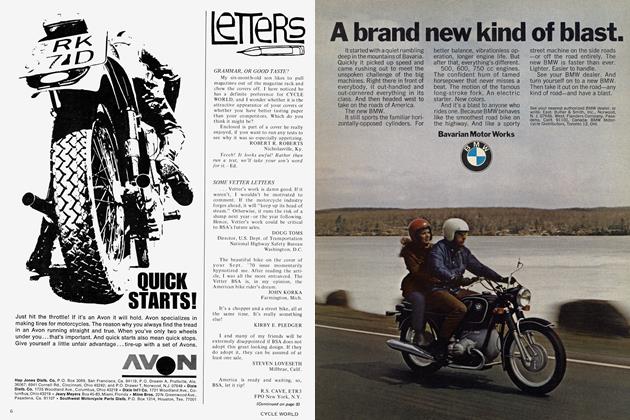

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1970 -

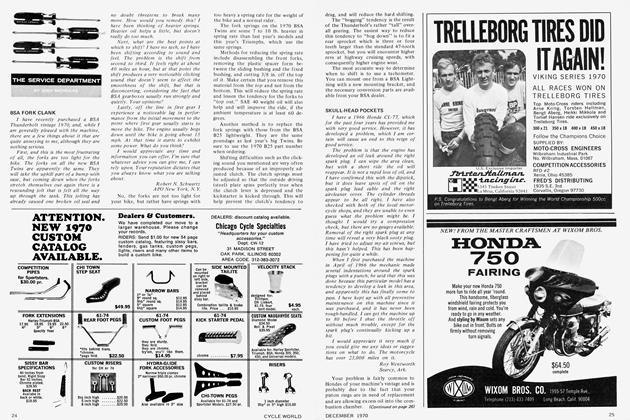

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

December 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

December 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features

FeaturesEuropean Touring

December 1970 By Stephen J. Herzog -

Features

FeaturesAnd Now...The Case For Traveling Light

December 1970 By Dan Hunt