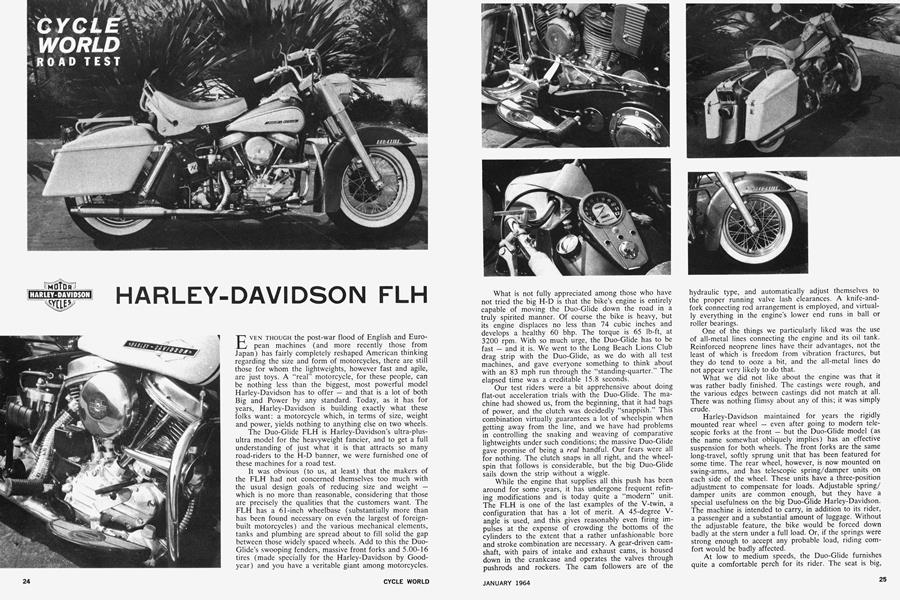

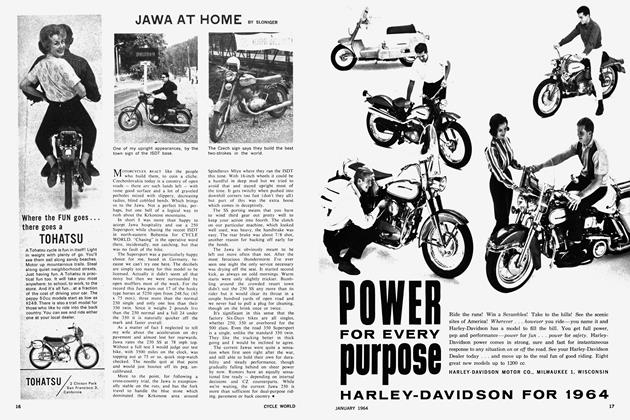

HARLEY-DAVIDSON FLH

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

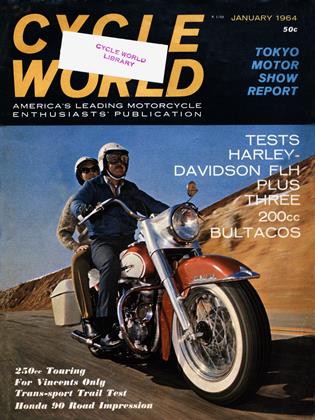

EVEN THOUGH the post-war flood of English and European machines (and more recently those from Japan) has fairly completely reshaped American thinking regarding the size and form of motorcycles, there are still those for whom the lightweights, however fast and agile, are just toys. A “real” motorcycle, for these people, can be nothing less than the biggest, most powerful model Harley-Davidson has to offer — and that is a lot of both Big and Power by any standard. Today, as it has for years, Harley-Davidson is building exactly what these folks want: a motorcycle which, in terms of size, weight and power, yields nothing to anything else on two wheels.

The Duo-Glide FLH is Harley-Davidson’s ultra-plusultra model for the heavyweight fancier, and to get a full understanding of just what it is that attracts so many road-riders to the H-D banner, we were furnished one of these machines for a road test.

It was obvious (to us, at least) that the makers of the FLH had not concerned themselves too much with the usual design goals of reducing size and weight — which is no more than reasonable, considering that those are precisely the qualities that the customers want. The FLH has a 61-inch wheelbase (substantially more than has been found necessary on even the largest of foreignbuilt motorcycles) and the various mechanical elements, tanks and plumbing are spread about to fill solid the gap between those widely spaced wheels. Add to this the DuoGlide’s swooping fenders, massive front forks and 5.00-16 tires (made specially for the Harley-Davidson by Goodyear) and you have a veritable giant among motorcycles.

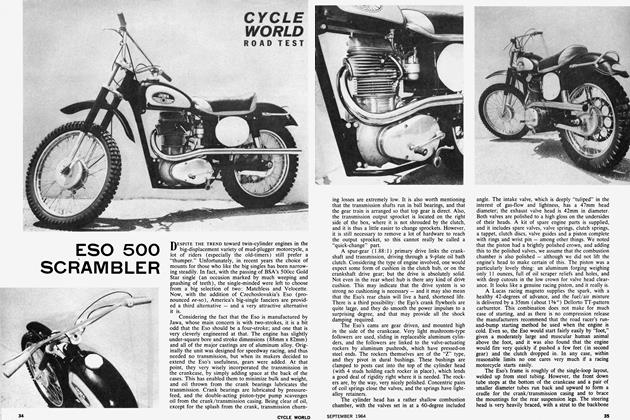

What is not fully appreciated among those who have not tried the big H-D is that the bike’s engine is entirely capable of moving the Duo-Glide down the road in a truly spirited manner. Of course the bike is heavy, but its engine displaces no less than 74 cubic inches and develops a healthy 60 bhp. The torque is 65 lb-ft, at 3200 rpm. With so much urge, the Duo-Glide has to be fast — and it is. We went to the Long Beach Lions Club drag strip with the Duo-Glide, as we do with all test machines, and gave everyone something to think about with an 83 mph run through the “standing-quarter.” The elapsed time was a creditable 15.8 seconds.

Our test riders were a bit apprehensive about doing flat-out acceleration trials with the Duo-Glide. The machine had showed us, from the beginning, that it had bags of power, and the clutch was decidedly “snappish.” This combination virtually guarantees a lot of wheelspin when getting away from the line, and we have had problems in controlling the snaking and weaving of comparative lightweights under such conditions; the massive Duo-Glide gave promise of being a real handful. Our fears were all for nothing. The clutch snaps in all right, and the wheelspin that follows is considerable, but the big Duo-Glide sails down the strip without a wiggle.

While the engine that supplies all this push has been around for some years, it has undergone frequent^ refining modifications and is today quite a “modern” unit. The FLH is one of the last examples of the V-twin, a configuration that has a lot of merit. A 45-degree Vangle is used, and this gives reasonably even firing impulses at the expense of crowding the bottoms of the cylinders to the extent that a rather unfashionable bore and stroke combination are necessary. A gear-driven camshaft, with pairs of intake and exhaust cams, is housed down in the crankcase and operates the valves through pushrods and rockers. The cam followers are of the hydraulic type, and automatically adjust themselves to the proper running valve lash clearances. A knife-andfork connecting rod arrangement is employed, and virtually everything in the engine’s lower end runs in ball or roller bearings.

One of the things we particularly liked was the use of all-metal lines connecting the engine and its oil tank. Reinforced neoprene lines have their advantages, not the least of which is freedom from vibration fractures, but they do tend to ooze a bit, and the all-metal lines do not appear very likely to do that.

What we did not like about the engine was that it was rather badly finished. The castings were rough, and the various edges between castings did not match at all. There was nothing flimsy about any of this; it was simply crude.

Harley-Davidson maintained for years the rigidly mounted rear wheel - even after going to modern telescopic forks at the front — but the Duo-Glide model (as the name somewhat obliquely implies) has an effective suspension for both wheels. The front forks are the same long-travel, softly sprung unit that has been featured for some time. The rear wheel, however, is now mounted on swing-arms, and has telescopic spring/damper units on each side of the wheel. These units have a three-position adjustment to compensate for loads. Adjustable spring/ damper units are common enough, but they have a special usefulness on the big Duo-Glide Harley-Davidson. The machine is intended to carry, in addition to its rider, a passenger and a substantial amount of luggage. Without the adjustable feature, the bike would be forced down badly at the stern under a full load. Or, if the springs were strong enough to accept any probable load, riding comfort would be badly affected.

At low to medium speeds, the Duo-Glide furnishes quite a comfortable perch for its rider. The seat is big, and soft, and the handlebars are rather high and very wide. Flat foot-rests are supplied, in place of the round pegs found on the rest of the world’s motorcycles. These flat rests proved to be quite comfortable while pottering around in town, but out on the open road, cruising at 6570 mph, wind and vibration try to slither the rider’s feet right off. The seat/handlebar combination, which sit the rider bolt-upright, are also just fine for riding at low speeds, but the wind at 70 mph pulls one’s arms out as tight as fiddle strings.

The last big Harley-Davidson we rode had a handshift, and the foot-operated lever on our test bike was a definite improvement. The present shifting-arrangement looks a trifle involved, with bits of hardware sprinkled here and there, but it does provide a good, positive control. It is almost impossible to miss a shift, if the lever is given a healthy yank,, and finding neutral is a snap. And, a light is provided, in the tank-top instrument cluster, to tell the rider when the transmission is in neutral. Riders who are accustomed to the soft snick-snick-snick shifting of the imported 40-inchers or, for that matter, the H-D Sportster will, however, find the pronounced “clank” produced as the Duo-Glide’s gears engage a bit annoying. Heavyweight enthusiasts tend to think of it as added proof of the substantial nature of Harley-Davidson’s machinery — and they may be right.

The Harlcy-Davidson’s clutch was a dandy. It will take the thunderous torque of the big, strong 74-cubic inch engine, and there is an over-centering helper spring in the clutch linkage that reduces the pressure required to disengage the clutch. Consequently, the clutch lever operates very easily; little muscle is necessary. There is, unfortunately, one undesirable side effect to having this “helper-spring” arrangement. When the helper-spring eases over center, the clutch tries to drop suddenly into engagement and until the rider learns to compensate for this sudden increase in spring tension at the handlebar control lever, his starts will be a trifle jerky. And, when making a drag-strip start, there isn’t much that can be done, period; you just wind-on throttle and let-fly with the clutch.

The Duo-Glide’s handling is somewhat better than one would expect, taking into consideration its size. It is, obviously, very stable at anything faster than a crawl, and neither side-winds nor rough roads disturb its majestic progress. Being so heavy, and having a soft, long-travel suspension, the Duo-Glide rides extremely smoothly, and when fitted with some sort of shielding to protect the rider from the wind it must be an uncommonly comfortable machine for trips of extended duration. Our only complaint about the Duo-Glide’s handling is that, after overcoming the sheer mass of the thing, too much miscellaneous hardware hangs out low on the sides of the machine, and if the rider attempts to “corner” the Duo-Glide very briskly, this hardware drags ferociously. One of our staff members, whose habit it is to corner somewhat more vigorously than is necessary, tried a bit of “ear-holing” with the Duo-Glide and found himself rasping along balanced on the kick-stand with the tires contacting the road very lightly indeed.

An unusual brake setup is employed on the DuoGlide. The front brake is cable operated, just like other motorcycles, but the rear brake is hydraulically operated. The foot brake, on the right-hand side of the machine, is hooked directly to a small combination master cylinder and hydraulic fluid reservoir, and metal and reinforced rubber piping, as in an automobile, takes the pressure back to the slave cylinder that actuates the rear brake shoes. Admittedly, this arrangement is a little involved, but it does give powerful braking at the rear wheel, and the brake action is much smoother than any cable or rod actuated brake we have tried. In a way, it is only proper that the rear brake should be so good; the front unit was smooth, but largely ineffectual insofar as a panic stop was concerned.

Cranking-off the Duo-Glide FLH was a man-size job. There were few times when it did not come to life after two or three good, hard kicks, but it takes a lot of effort to run the engine through even once. Actually, a moderately muscular 170-pounder will have no difficulty, but if you happen to fall into the 130-140 pound class, you may need both feet on the pedal and an anvil in your pocket on a cold winter morning.

The Duo-Glide has a four-speed transmission, and would function surprisingly well with only high-gear. There is so much torque that the rider can, once he gets rolling, simply poke it into top cog and leave it there. The power delivery is smooth enough so that there is virtually no chain-snatch until the bike gets down to about 15 mph in fourth, and the engine will haul the bike and its rider up to 80 mph in an astonishingly short time without bothering with such trifles as downshifting. With this machine, Harley-Davidson has proved that enough torque is very nearly the equivalent of an automatic transmission.

The fuel consumption rate of the Duo-Glide FLH was nothing short of phenomenal. For all-around, mixed town and country riding, we got just about 30 miles per gallon. This would not have been too objectionable had it not been for the limited fuel tank capacity. The tank holds less than four gallons, and unless the rider wants to press his luck he will have to stop for fuel about every hundred miles. And, there are stretches out in the west where it is at least that far between service stations. Perhaps it might be possible to fit one of the voluminous molded-fiberglass “saddle bags” with a filler cap so that it could be used as an extra tank.

Our test machine was a reasonably “bare” version of the basic Duo-Glide model. The FOB price of this machine is $1450, and with the accessories supplied on our particular bike (chromed wheels, buddy seat, saddle bags, “Hi-Fi” red paint, etc.) the price before shipping and setup charges, taxes and license was $1637.40. A lot of money, compared to other bikes; but the Duo-Glide is not other bikes, and if you want to break it down into a price per pound, it is a bargain.

There is really no middle ground where the big Harley-Davidson is concerned. Riders who like them will have nothing else; and those whose fancy is inclined more toward the lightweights think all that bulk is absurd. And, as motorcyclists tend to be individualistic in any case, with strong opinions, the battle (usually only verbal) between these factions waxes heavy, as it has for the past 15 years. There are cries of “Lousy Limey Pipsqueak” from one side of the fence, and the gleeful retort “Hawg” from the other, and to the best of our knowledge, no one has, as yet, convinced anyone of anything.

From the standpoint of the tourist road-rider, HarleyDavidson’s Duo-Glide FLH has a lot to offer. It will carry almost any load, without an appreciable drop in performance, and while the buddy seat is not the best spot in the world for a “buddy,” it does offer the rider soft, cushioned seating. Reliability is of prime importance for the man setting out from Fairbanks, headed for Miami, and the big, strong, slow-turning FLH engine gives one a good chance of making such a trip without incident. The engine simply doesn’t have to work very hard to carry the bike and its load at touring speeds. Faced with a coast-to-coast trip by motorcycle, the Duo-Glide (equipped with a big, tall windshield) would be a mighty good choice. •

H ARLE Y-DAVIDSON FLH

SPECIFICATIONS

$1673

PERFORMANCE