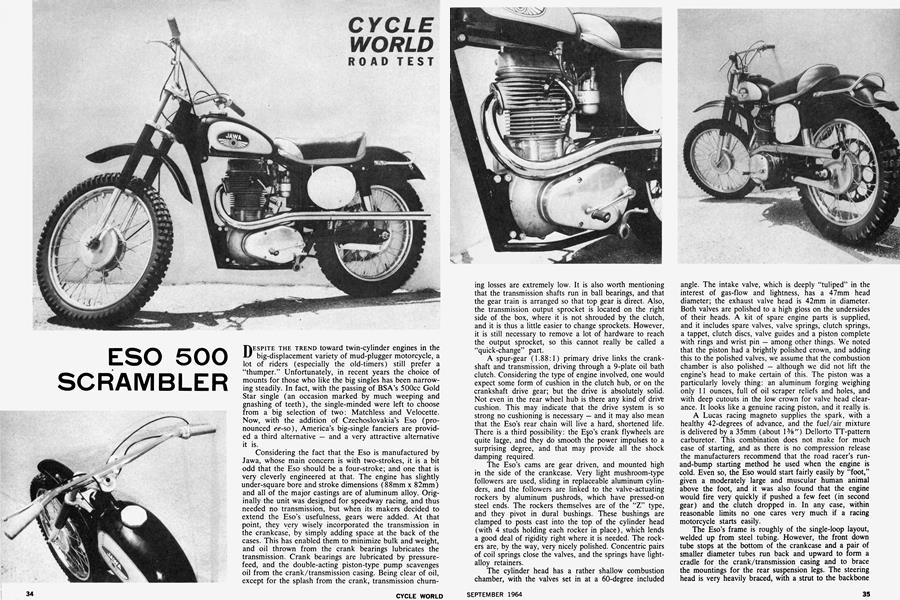

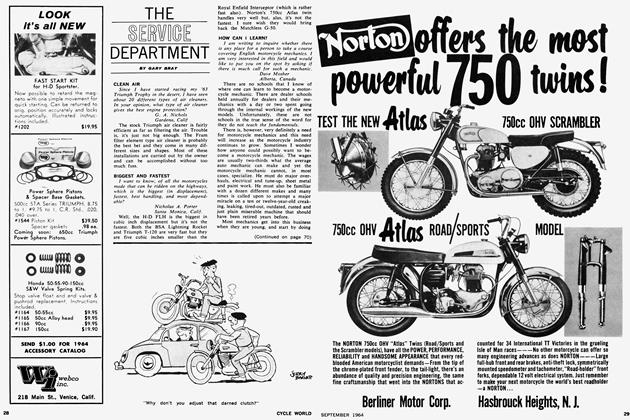

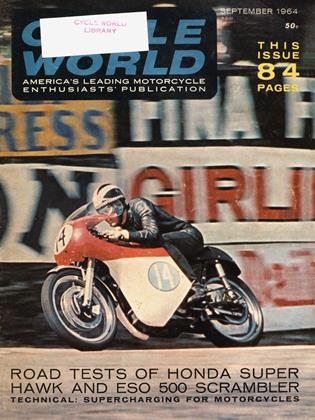

ESO 500 SCRABLER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

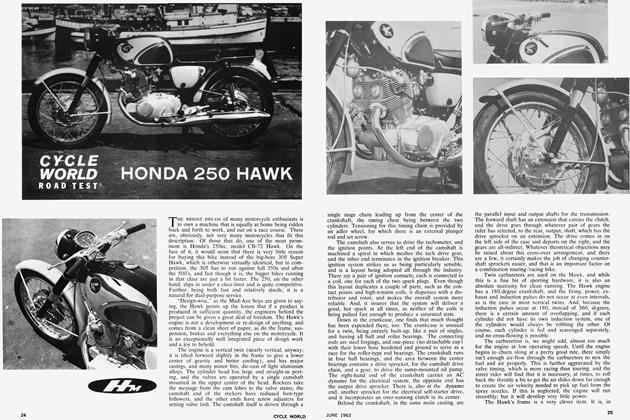

DESPITE THE TREND toward twin-cylinder engines in the big-displacement variety of mud-plugger motorcycle, a lot of riders (especially the old-timers) still prefer a “thumper.” Unfortunately, in recent years the choice of mounts for those who like the big singles has been narrowing steadily. In fact, with the passing of BSA’s 500cc Gold Star single (an occasion marked by much weeping and gnashing of teeth), the single-minded were left to choose from a big selection of two: Matchless and Velocette. Now, with the addition of Czechoslovakia’s Eso (pronounced ee-so), America’s big-single fanciers are provided a third alternative — and a very attractive alternative it is.

Considering the fact that the Eso is manufactured by Jawa, whose main concern is with two-strokes, it is a bit odd that the Eso should be a four-stroke; and one that is very cleverly engineered at that. The engine has slightly under-square bore and stroke dimensions (88mm x 82mm) and all of the major castings are of aluminum alloy. Originally the unit was designed for speedway racing, and thus needed no transmission, but when its makers decided to extend the Eso’s usefulness, gears were added. At that point, they very wisely incorporated the transmission in the crankcase, by simply adding space at the back of the cases. This has enabled them to minimize bulk and weight, and oil thrown from the crank bearings lubricates the transmission. Crank bearings are lubricated by pressurefeed, and the double-acting piston-type pump scavenges oil from the crank/transmission casing. Being clear of oil, except for the splash from the crank, transmission churning losses are extremely low. It is also worth mentioning that the transmission shafts run in ball bearings, and that the gear train is arranged so that top gear is direct. Also, the transmission output sprocket is located on the right side of the box, where it is not shrouded by the clutch, and it is thus a little easier to change sprockets. However, it is still necessary to remove a lot of hardware to reach the output sprocket, so this cannot really be called a “quick-change” part.

A spur-gear (1.88:1) primary drive links the crankshaft and transmission, driving through a 9-plate oil bath clutch. Considering the type of engine involved, one would expect some form of cushion in the clutch hub, or on the crankshaft drive gear; but the drive is absolutely solid. Not even in the rear wheel hub is there any kind of drive cushion. This may indicate that the drive system is so strong no cushioning is necessary — and it may also mean that the Eso’s rear chain will live a hard, shortened life. There is a third possibility: the E§o’s crank flywheels are quite laçge, and they do smooth the power impulses to a surprising degree, and that may provide all the shock damping required.

The Eso’s cams are gear driven, and mounted high in the side of the crankcase. Very light mushroom-type followers are used, sliding in replaceable aluminum cylinders, and the followers are linked to the valve-actuating rockers by aluminum pushrods, which have pressed-on steel ends. The rockers themselves are of the “Z” type, and they pivot in dural bushings. These bushings are clamped to posts cast into the top of the cylinder head (with 4 studs holding each rocker in place), which lends a good deal of rigidity right where it is needed. The rockers are, by the way, very nicely polished. Concentric pairs of coil springs close the valves, and the springs have lightalloy retainers.

The cylinder head has a rather shallow combustion chamber, with the valves set in at a 60-degree included angle. The intake valve, which is deeply “tuliped” in the interest of gas-flow and lightness, has a 47mm head diameter; the exhaust valve head is 42mm in diameter. Both valves are polished to a high gloss on the undersides of their heads. A kit of spare engine parts is supplied, and it includes spare valves, valve springs, clutch springs, a tappet, clutch discs, valve guides and a piston complete with rings and wrist pin — among other things. We noted that the piston had a brightly polished crown, and adding this to the polished valves, we assume that the combustion chamber is also polished — although we did not lift the engine’s head to make certain of this. The piston was a particularly lovely thing: an aluminum forging weighing only 11 ounces, full of oil scraper reliefs and holes, and with deep cutouts in the low crown for valve head clearance. It looks like a genuine racing piston, and it really is.

A Lucas racing magneto supplies the spark, with a healthy 42-degrees of advance, and the fuel/air mixture is delivered by a 35mm (about Wa") Dellorto TT-pattern carburetor. This combination does not make for much ease of starting, and as there is no compression release the manufacturers recommend that the road racer’s runand-bump starting method he used when the engine is cold. Even so, the Eso would start fairly easily by “foot,” given a moderately large and muscular human animal above the foot, and it was also found that the engine would fire very quickly if pushed a few feet (in second gear) and the clutch dropped in. In any case, within reasonable limits no one cares very much if a racing motorcycle starts easily.

The Eso’s frame is roughly of the single-loop layout, welded up from steel tubing. However, the front down tube stops at the bottom of the crankcase and a pair of smaller diameter tubes run back and upward to form a cradle for the crank/transmission casing and to brace the mountings for the rear suspension legs. The steering head is very heavily braced, with a strut to the backbone tube and an elaborate sheet-metal gusset. The engine mounting consists of small ears welded to the frame tubes, and it appears that the entire power unit could be pulled after removing only 6 bolts.

Jawa’s excellent moto-cross forks are used on the Eso, and they provide a mighty 6-inches of travel for the front wheel. The rear wheel has 4-inches of travel, and there is highly satisfactory damping for both wheels. The Eso is particularly well suited to crash and bash cross-country riding. The only fault we could find with the “chassis” layout was the combination of a 21-inch wheel and smallsection tire at the front. European riders seem to like the bike set up that way, but most Americans would prefer a 19-inch front wheel with a 3.50 or 4.00 section tire.

To meet riding conditions in the west, it will also be necessary to add an air filter. In the stock Eso layout, the carburetor air-horn is shrouded by an enclosure under the seat (which also houses the oil tank). This will prevent gravel and small birds from being drawn into the engine, but not dust or sand. Also, most riders would, we think, want to add a hinge to the seat mounting. The seat is held on by a couple of bolts, and is easy to remove, but it must be unbolted every time the rider wants to check the oil level and that is a trifle inconvenient.

In general, the control layout was good, but none of us liked the handlebars, and we think that the left-foot shift will be awkward for most of the riders who would buy an Eso. Foot pegs are always a problem on a scrambler or moto-cross machine: the rider needs secure footing; yet long pegs will invariably be knocked off or bent back by some strategically-placed rock or stump. On the Eso, the pegs are rather short, but they have cleats to provide a good footing, and they are very solidly mounted. Our objection to the bars was because they were too high, except when actually standing on the pegs. Of course, the bars are easily changed, and every rider has his own preference so the handlebars on a new machine are usually replaced or modified in any case.

Being built for European moto-cross events, the Eso is balanced for very rough terrain, where the better riders will blast along with the front wheel in the air, steering the machine with the foot pegs (Dave Bickers says that’s how he does it). Accordingly, the Eso carries much of its weight on the rear wheel, and the combination of this weight bias and the thunderous torque from the engine makes it almost too easy to get the front wheel elevated. But, for really rough going, the only way to get through rapidly is to lift the front wheel over the humps and use power to make the rear wheel climb them, which is what the Eso does very neatly. On the other hand, this sort of setup makes the front end too light to get a good bite in tight, flat turns, and the small-section tire does tend to skid under such conditions. In all, the Eso will seem a bit strange to those who are accustomed to smooth, fast scramble courses; and perfect for those experienced in real moto-cross competition. The former will not like the way the front wheel skids; the latter will appreciate the fact that in even the roughest going, the Eso’s front end does not flap or bottom. By and large, this means that the Eso will seem perfect for scrambles races in the east; but will require some reworking for western events.

In any kind of conditions the Eso engine’s wide range of power will be useful. It will “rev” reasonably well, but its broad torque curve is its best feature — which should lay to rest that business about short-stroke engines having poor torque characteristics. The 4-speed gearbox is there to use, obviously, and the Eso will do best if full use is made of the gears; but it will also slog along in top gear like a trials machine.

Except for the engine, virtually everything on the Eso is made of steel, and it is a very sturdy machine; but it weighs only 296 pounds, full of gas and oil, and ready to ride. At that weight, it is not the lightest motorcycle around, but it is light for a 500, and the substitution of aluminum for steel in the tank and fenders, and a little judicious trimming and drilling here and there, could bring the weight down to that of the 250cc Jawa moto-cross machine. With or without this weight-trimming, the Eso is a potential winner. It has impressed all of the CW staff very favorably, and after a few get into circulation, it should make quite an impression on everyone concerned.

ESO

500 SCRAMBLER

$970.00

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue