THE SCENE

IVAN J. WAGAR

IT is a fair bet that very few motorcyclists in this country have ever heard of Bean Canyon. If, however, a current test case involving some 150 motorcyclists is successful, we could be entering an era of complete strangulation of our sport, marked by severe restrictions on every citizen’s right to use and enjoy public land.

Situated in Kern County, Bean Canyon has been a favorite Southern California off-road riding area for years. There are miles and miles of nothing but good riding country, all of it federal land. Now the sticky part. Bean Canyon is surrounded by privately owned land, and the only access is through usually unposted, unfenced property. One of the land owners, Roger Nichols, decided he did not want motorcycle riders crossing his property. Nichols contacted Sgt. Ben Austin of the Kern County Sheriff’s Dept, to complain about the damage done to his land by the motorcyclists and the frequent hostile attitude of some of the riders he had encountered.

At this point it should be established that Austin is a pretty fair guy. He was sympathetic to Nichols’ complaints, but pointed out the problem of enforcement. It takes Austin a full hour to negotiate the narrow, two-rut road to the Nichols property, and usually the riders are elsewhere when he arrives.

This original complaint went back to August, 1968, and in late 1969 Nichols, with the help of deputies, staked out and posted his property as being off limits to motorcycle riders. Fair enough.

On returning to the property in the spring, Nichols found the fences torn down and considerable litter about the place. Whether this damage was caused by motorcyclists or hunters is debatable, but the fact remains that Nichols, quite understandably, was unhappy. About this time Nichols decided to hire some reserve deputies to police the use of his land.

The deputies, in some cases claiming to be conducting a survey, took down names and addresses of motorcyclists as they entered the canyon. Then the bombshell. In some cases more than six months later, the motorcyclists received a letter from Judge William L. Woods requesting $65 bail on a charge of trespassing, if the accused does not wish to appear. If the rider does appear, the bail will be reduced to $35.

Realizing that most of these 150 riders probably rode through after the fencing and signs were removed, this becomes pretty heavy action. But there is a more far-reaching consequence to the whole episode, and one that could eventually affect the freedom of every person in this country: closing the

waterhole. For a couple of hundred years it has been an accepted right that a person can cross private property to reach a waterhole or grazing land, or use an established trail to reach federal or public land.

If, on the other hand, the Nichols suit against 150 individuals for damage to his property is upheld and becomes a precedent, it could only mean that any road user might be liable to a fine any time the wheels of his vehicle touch private property. A horseman, hunter, hiker, bicyclist, or anyone on private property, marked or unmarked, could, under this legal precedent, be liable if the owner considered a footprint damaging to his property.

The Bureau of Land Management, realizing that there is no permanent damage to the canyon by motorcycles, is working very hard to find an access route to the area. But while the BLM realizes the need for recreation land for the citizens, yet another owner, Bob Munroe, has hired sheriffs to “survey” people crossing his land to get to Bean Canyon.

Why do the Nicholses and Munroes of this world hate motorcycles? I really don’t think the reason is damage to the property so much as it is their dislike of motorcycles because of their noise.

I have discussed the “motorcycle problem” with many legislators. During these encounters, in some cases, I have managed to convince these people that the motorcycle can be a passive vehicle. The motorcycle does not destroy our land, pollute our air nor does it use unnecessary space on our roads.

No matter how strongly these legislators feel about the issue in question, be it land use, motorcycle fatalities, or whatever, when the topic is settled, we almost always have to sit through the big gripe about noise. The continual second-rate bitching about noise, in fact, very quickly makes one realize that noise makes people hate motorcycles. Now when the common citizen hates motorcycles, we have a problem. But when elected officials (legislators) know that motorcyclists represent a very small portion of the voters, we no longer have a problem, we have a crisis.

If we know that noise from motorcycles may rate a higher priority than smog or water pollution with some elected officials, it would seem that all we have to do is adopt and enforce noise laws. But, Tonto’s reply to the Lone Ranger when they were surrounded by bloodthirsty Indians, “What do you mean WE, white man,” very well applies here. Motorcycle dealers will never stop making a buck on noise conversions as long as their suppliers continue to produce two-stroke motorcycles with expansion chambers for sale to the general public. The next very obvious question must relate to the burden of responsibility.

Certainly, the manufacturers will continue to supply fully race-equipped machines. And there is no way we can expect a dealer to have any conscience about selling or preparing loud machines, even when he knows it will be used in town. One local dealer recently fitted a pair of straight pipes free, in exchange for the almost new mufflers on a CB350 Honda. The owner, a young student, will probably cause several dozen or even hundreds of non-motorcyclists to further dislike all motorcycles—something we cannot afford.

An executive of one of the motorcycle companies in this country recently told me that his company will continue to sell machines with expansion chambers because a racing machine out in the desert, miles from anywhere, does no harm. That is true. But every day it becomes more difficult to be miles from other people, even in the desert areas.

This same executive agrees that noise pollution is responsible for land closure, but does not feel it is industry’s responsibility to do anything about the situation. Unfortunately, too many people in motorcycling have the feeling that the other guy is the one to blame for any problems. From the individual rider to the manufacturers, a ridiculous attitude of complacency prevents a positive step toward eliminating our number one enemy—noise.

It is the responsibility of the member firms in the Motorcycle Industry Council to agree on a maximum noise level for all motorcycles sold in this country. An additional step would be to begin now to permit only fully muffled machines in AMA Sportsman racing. I have been told by Tom Clark, AMA’s director of professional racing, that only street legal machines are permitted to enter AMA enduros in Ohio. This requirement is not because of the need for lights or any other street gear, but because of mufflers. If the riders remove the muffler during the event, there is a heavy loss of points at the finish. This is a very positive step toward a solution. But it has the flavor of being a regulation, and will, to some people, be unpalatable because it represents the establishment enforcing its desires.

How much better it would be if we took the glamour out of noisy machines. Industry can produce quiet motorcycles that are just as powerful as current racers. When we consider that almost all of our present motocross heroes will lose up to 50 percent of their hearing by age 35, I don’t think we can continue to tolerate Industry’s irresponsibility.

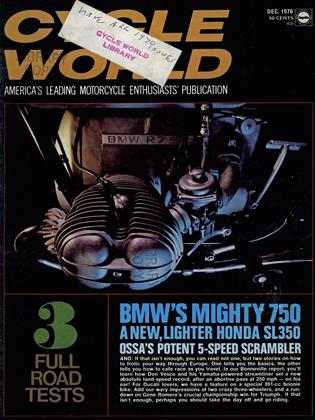

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

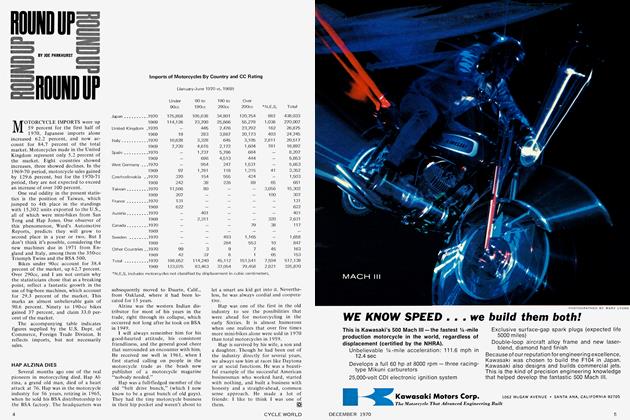

DepartmentsRound Up

December 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

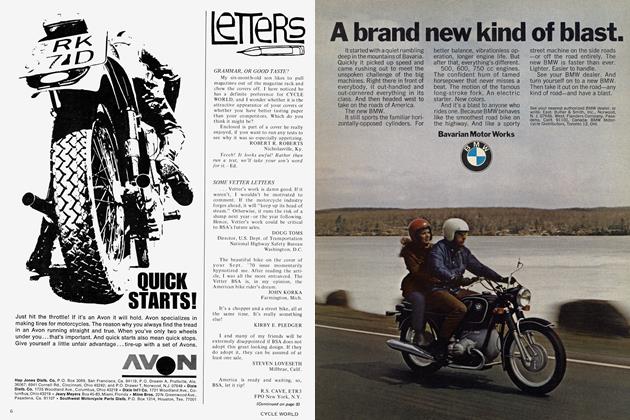

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

December 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

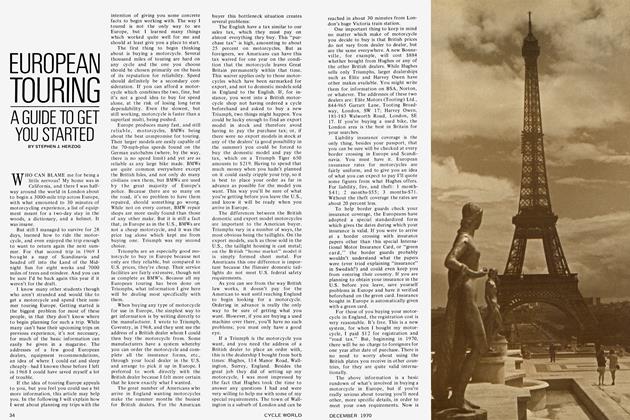

Features

FeaturesEuropean Touring

December 1970 By Stephen J. Herzog -

Features

FeaturesAnd Now...The Case For Traveling Light

December 1970 By Dan Hunt -

Competition

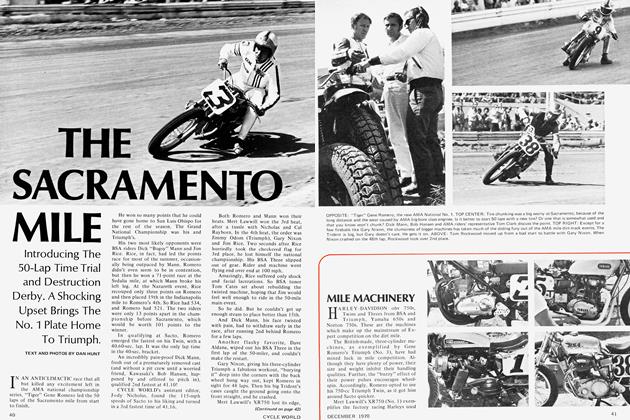

CompetitionThe Sacramento Mile

December 1970 By Dan Hunt