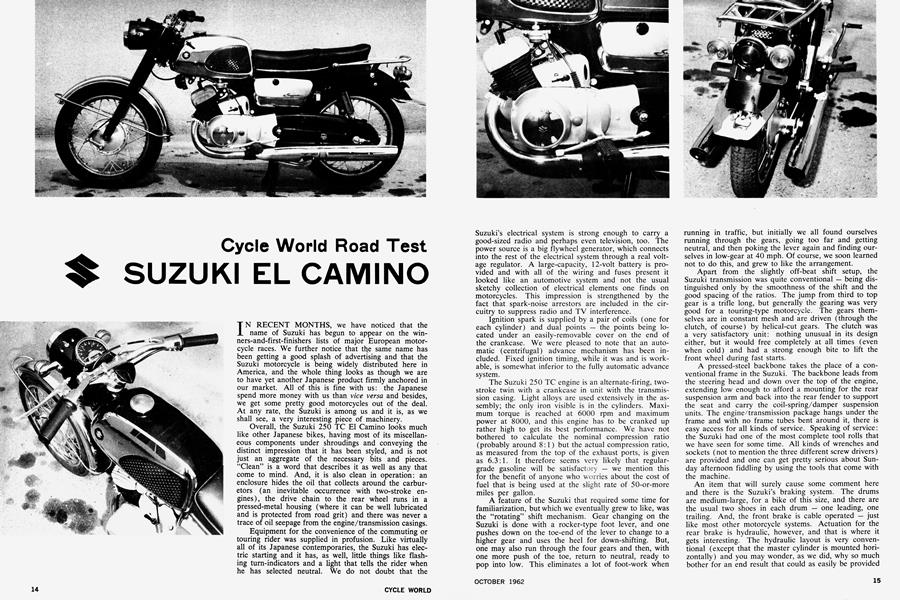

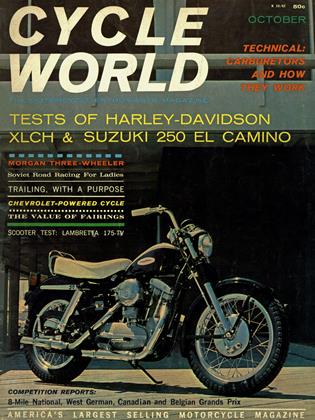

SUZUKI EL CAMINO

Cycle World Road Test

IN RECENT MONTHS, we have noticed that the name of Suzuki has begun to appear on the winners-and-first-finishers lists of major European motorcycle races. We further notice that the same name has been getting a good splash of advertising and that the Suzuki motorcycle is being widely distributed here in America, and the whole thing looks as though we are to have yet another Japanese product firmly anchored in our market. All of this is fine with us: the Japanese spend more money with us than vice versa and besides, we get some pretty good motorcycles out of the deal. At any rate, the Suzuki is among us and it is, as we shall see, a very interesting piece of machinery.

Overall, the Suzuki 250 TC El Camino looks much like other Japanese bikes, having most of its miscellaneous components under shroudings and conveying the distinct impression that it has been styled, and is not just an aggregate of the necessary bits and pieces. “Clean” is a word that describes it as well as any that come to mind. And, it is also clean in operation: an enclosure hides the oil that collects around the carburetors (an inevitable occurrence with two-stroke engines), the drive chain to the rear wheel runs in a pressed-metal housing (where it can be well lubricated and is protected from road grit) and there was never a trace of oil seepage from the engine/transmission casings.

Equipment for the convenience of the commuting or touring rider was supplied in profusion. Like virtually all of its Japanese contemporaries, the Suzuki has electric starting and it has, as well, little things like flashing turn-indicators and a light that tells the rider when he has selected neutral. We do not doubt that the Suzuki’s electrical system is strong enough to carry a good-sized radio and perhaps even television, too. The power source is a big flywheel generator, which connects into the rest of the electrical system through a real voltage regulator. A large-capacity, 12-volt battery is provided and with all of the wiring and fuses present it looked like an automotive system and not the usual sketchy collection of electrical elements one finds on motorcycles. This impression is strengthened by the fact that spark-noise arrestors are included in the circuitry to suppress radio and TV interference.

Ignition spark is supplied by a pair of coils (one for each cylinder) and dual points — the points being located under an easily-removable cover on the end of the crankcase. We were pleased to note that an automatic (centrifugal) advance mechanism has been included. Fixed ignition timing, while it was and is workable, is somewhat inferior to the fully automatic advance system.

The Suzuki 250 TC engine is an alternate-firing, twostroke twin with a crankcase in unit with the transmission casing. Light alloys are used extensively in the assembly; the only iron visible is in the cylinders. Maximum torque is reached at 6000 rpm and maximum power at 8000, and this engine has to be cranked up rather high to get its best performance. We have not bothered to calculate the nominal compression ratio (probably around 8:1) but the actual compression ratio, as measured from the top of the exhaust ports, is given as 6.3:1. It therefore seems very likely that regulargrade gasoline will be satisfactory — we mention this for the benefit of anyone who worries about the cost of fuel that is being used at the slight rate of 50-or-more miles per gallon.

A feature of the Suzuki that required some time for familiarization, but which we eventually grew to like, was the “rotating” shift mechanism. Gear changing on the Suzuki is done with a rocker-type foot lever, and one pushes down on the toe-end of the lever to change to a higher gear and uses the heel for down-shifting. But, one may also run through the four gears and then, with one more push of the toe, return to neutral, ready to pop into low. This eliminates a lot of foot-work when running in traffic, but initially we all found ourselves running through the gears, going too far and getting neutral, and then poking the lever again and finding ourselves in low-gear at 40 mph. Of course, we soon learned not to do this, and grew to like the arrangement.

Apart from the slightly off-beat shift setup, the Suzuki transmission was quite conventional — being distinguished only by the smoothness of the shift and the good spacing of the ratios. The jump from third to top gear is a trifle long, but generally the gearing was very good for a touring-type motorcycle. The gears themselves are in constant mesh and are driven (through the clutch, of course) by helical-cut gears. The clutch was a very satisfactory unit: nothing unusual in its design either, but it would free completely at all times (even when cold) and had a strong enough bite to lift the front wheel during fast starts.

A pressed-steel backbone takes the place of a conventional frame in the Suzuki. The backbone leads from the steering head and down over the top of the engine, extending low enough to afford a mounting for the rear suspension arm and back into the rear fender to support the seat and carry the coil-spring/damper suspension units. The engine/transmission package hangs under the frame and with no frame tubes bent around it, there is easy access for all kinds of service. Speaking of service: the Suzuki had one of the most complete tool rolls that we have seen for some time. All kinds of wrenches and sockets (not to mention the three different screw drivers) are provided and one can get pretty serious about Sunday afternoon fiddling by using the tools that come with the machine.

An item that will surely cause some comment here and there is the Suzuki’s braking system. The drums are medium-large, for a bike of this size, and there are the usual two shoes in each drum — one leading, one trailing. And, the front brake is cable operated — just like most other motorcycle systems. Actuation for the rear brake is hydraulic, however, and that is where it gets interesting. The hydraulic layout is very conventional (except that the master cylinder is mounted horizontally) and you may wonder, as we did, why so much bother for an end result that could as easily be provided by a simple pull-rod and lever. The answer lies with another model in the Suzuki line, the 250 TA: this machine has hydraulic brakes both front and reaf, operated from the foot pedal. The handlebar lever is there, too, and it functions as a sort of emergency system, actuating the brakes mechanically (through cables). The 250 TC system is half-way between this automotive-style system and the conventional layout; hence, the hydraulic rear brake. We found ourselves almost wishing they had retained the full hydraulic system for the 250 TC; our test machine certainly showed no braking deficiencies, but the notion of one-control braking intrigues us.

There were other features to be found on the Suzuki that one does not ordinarily see. The twin-carburetor setup was a particularly clever bit of work: the carburetors have float chambers located around the main jet and emulsion chamber (with a double float) and tilting of these carburetors has virtually no effect on the fuel level. Each carburetor has a choke butterfly for cold starting, with ticklers on the floats, and all of the adjusting screws are easily reached. Fuel is fed to these from the tank through a combination fuel shut-off and reserve valve with a built-in filter bowl. There is little excuse for ever having to use the reserve supply, for a small plastic pipe running up the front of the tank shows the fuel level at a glance.

Our test machine had only slightly over 200 miles on the odometer when we began to flog it up and down ourtest course. This was, as events proved, too little a breaking-in period as the new bike was much too tight to be ridden hard. The owner’s manual cautions against fast running until the break-in period is past; the Suzuki needs at least 1000 miles of gentle running (the manual outlines the speed and distance stages) before sustained full throttle can be used.

Tight engine or no tight engine, the 250 TC was quite fast for a 15 cubic inch touring machine. Its top speed of 83 mph is very respectable, and the acceleration will insure that you do not get in anyone’s way. The figures do not show how smooth the bike is: it has a period of vibration at about 5000 rpm, but that is all. We thought that it was a very satisfactory sport/touring bike, as it had excellent handling and would cruise comfortably at 65 — the engine is cranking over at a rapid rate, but it doesn’t feel strained. The ride was good, too, and we used the Suzuki for all of our errands during the time it was in our hands. It would start with less fuss and haul us around in more comfort than almost anything we had available — and that included a couple of staff-owned automobiles. And, finally, the Suzuki was a lot of fun to ride.

SUZUKI EL CAMINO

SPECIFICATIONS

$625.00

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle Round Up

OCTOBER 1962 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

OCTOBER 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

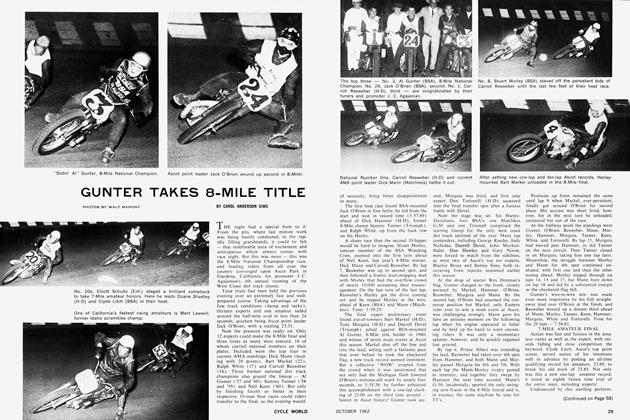

Gunter Takes 8-Mile Title

OCTOBER 1962 By Carol Anderson Sims -

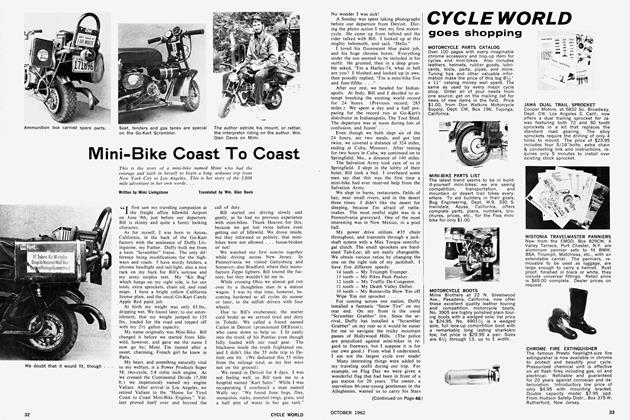

Mini-Bike Coast To Coast

OCTOBER 1962 By Mimi Livingstone -

Soviet Road Racing Championships For Women

OCTOBER 1962 By Anke-Eve Goldmann -

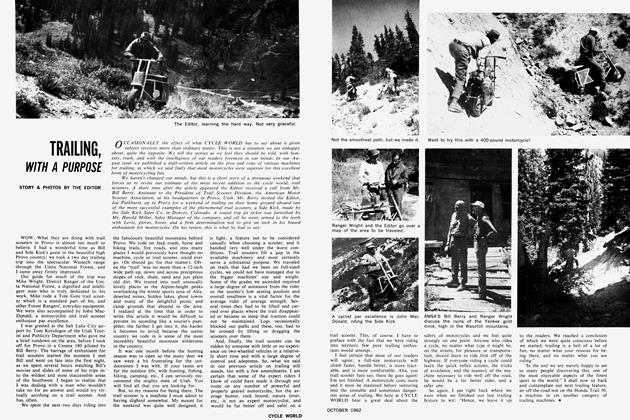

Trailing, With A Purpose

OCTOBER 1962