THE SPACE AGE TURBO-CYCLE "DEATH WISH"

It goes whoosh, Turns 100,000 rpm, and Trails White Nitrate Smoke

JAMES JOSEPH

I ALWAYS RIDE SCARED,” concedes handsome Larry Gran, 25, a computer programmer who, after a score of rides—one of them at better than 150 mph—still hasn’t computed either his odds for survival or precisely when his turbine-engined “Death Wish,” the world’s first turbo-cycle, will crack the existing quarter-mile record. But both Gran and co-owner/designer Roy Hamilton, of San Diego’s REV Specialties, are sure their machine will do it.

"We're taking things slow," Hamilton shrugged recently after Death Wish, with Gran aboard, had done the San Fernando (Calif.) strip in a best-of-three 122 mph.

What’s been slowing Death Wish is bearing trouble. That’s understandable, considering her space age power plant: a 350-bhp turbine engine (Turbonique’s “Microturbo S-12”) which at full throttle revs to an awesome 100,000 rpm, burns exotic ($5 per gallon) selfoxidizing propyl nitrate and chain-drives the turbo-bike’s go-wheel (fitted with a 5to 7-in. wide racing tread, slicks aren’t required) at something like 2200 rpm.

Though the Turbonique turbine engine—which more closely resembles a rocket than Indy’s banned turbines-has been around for awhile, Gran and Hamilton are the first to successfully mate it to two wheels. Still, in terms of turbine efficiency, Gran has scarcely yet cracked the throttle. On his fastest go he’s used only a little more than half power.

“Even half open, you get a tremendous belt in the back...like not just one mule, but a whole team kicking you down the strip,” winces Gran.

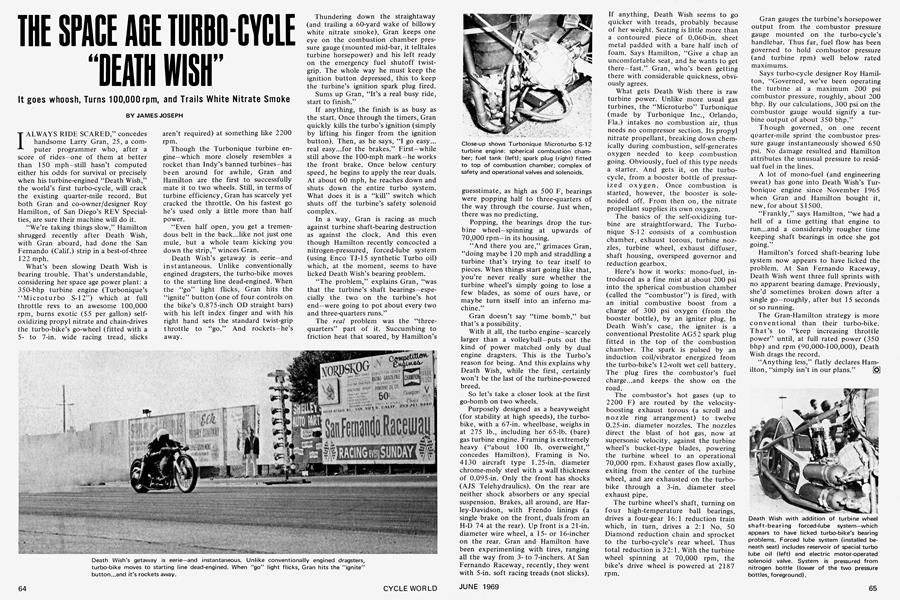

Death Wish’s getaway is eerie—and instantaneous. Unlike conventionally engined dragsters, the turbo-bike moves to the starting line dead-engined. When the “go” light ñicks, Gran hits the “ignite” button (one of four controls on the bike’s 0.875-inch OD straight bars) with his left index finger and with his right hand sets the standard twist-grip throttle to “go.” And rockets—he’s away.

Thundering down the straightaway (and trailing a 60-yard wake of billowy white nitrate smoke), Gran keeps one eye on the combustion chamber pressure gauge (mounted mid-bar, it telltales turbine horsepower) and his left ready on the emergency fuel shutoff twistgrip. The whole way he must keep the ignition button depressed, this to keep the turbine’s ignition spark plug fired.

Sums up Gran, “It’s a real busy ride, start to finish.”

If anything, the finish is as busy as the start. Once through the timers, Gran quickly kills the turbo’s ignition (simply by lifting his finger from the ignition button). Then, as he says, “I go easy... real easy...for the brakes.” First—while still above the 100-mph mark—he works the front brake. Once below century speed, he begins to apply the rear duals. At about 60 mph, he reaches down and shuts down the entire turbo system. What does it is a “kill” switch which shuts off the turbine’s safety solenoid complex.

In a way, Gran is racing as much against turbine shaft-bearing destruction as against the clock. And this even though Hamilton recently concocted a nitrogen-pressured, forced-lube system (using Eneo TJ-15 synthetic Turbo oil) which, at the moment, seems to have licked Death Wish’s bearing problem.

“The problem,” explains Gran, “was that the turbine’s shaft bearings—especially the two on the turbine’s hot end—were going to pot about every two and three-quarters runs.”

The real problem was the “threequarters” part of it. Succumbing to friction heat that soared, by Hamilton’s guesstimate, as high as 500 F, bearings were popping half to three-quarters of the way through the course. Just when, there was no predicting.

Popping, the bearings drop the turbine wheel—spinning at upwards of 70,000 rpm—in its housing.

“And there you are,” grimaces Gran, “doing maybe 120 mph and straddling a turbine that’s trying to tear itself to pieces. When things start going like that, you’re never really sure whether the turbine wheel’s simply going to lose a few blades, as some of ours have, or maybe turn itself into an inferno machine.”

Gran doesn’t say “time bomb,” but that’s a possibility.

With it all, the turbo engine—scarcely larger than a volleyball—puts out the kind of power matched only by dual engine dragsters. This is the Turbo’s reason for being. And this explains why Death Wish, while the first, certainly won’t be the last of the turbine-powered breed.

So let’s take a closer look at the first go-bomb on two wheels.

Purposely designed as a heavyweight (for stability at high speeds), the turbobike, with a 67-in. wheelbase, weighs in at 275 lb., including her 65-lb. (bare) gas turbine engine. Framing is extremely heavy (“about 100 lb. overweight,” concedes Hamilton). Framing is No. 4130 aircraft type 1.25-in. diameter chrome-moly steel with a wall thickness of 0.095-in. Only the front has shocks (AJS Telehydraulics). On the rear are neither shock absorbers or any special suspension. Brakes, all around, are Harley-Davidson, with Frendo linings (a single brake on the front, duals from an H-D 74 at the rear). Up front is a 21-in. diameter wire wheel, a 15or 16-incher on the rear. Gran and Hamilton have been experimenting with tires, ranging all the way from 3to 7-inchers. At San Fernando Raceway, recently, they went with 5-in. soft racing treads (not slicks). If anything, Death Wish seems to go quicker with treads, probably because of her weight. Seating is little more than a contoured piece of 0.060-in. sheet metal padded with a bare half inch of foam. Says Hamilton, “Give a chap an uncomfortable seat, and he wants to get there—fast.” Gran, who’s been getting there with considerable quickness, obviously agrees.

What gets Death Wish there is raw turbine power. Unlike more usual gas turbines, the “Microturbo” Turbonique (made by Turbonique Inc., Orlando, Fla.) intakes no combustion air, thus needs no compressor section. Its propyl nitrate propellant, breaking down chemically during combustion, self-generates oxygen needed to keep combustion going. Obviously, fuel of this type needs a starter. And gets it, on the turbocycle, from a booster bottle of pressurized oxygen. Once combustion is started, however, the booster is solenoided off. From then on, the nitrate propellant supplies its own oxygen.

The basics of the self-oxidizing turbine are straightforward. The Turbonique S-12 consists of a combustion chamber, exhaust torous, turbine nozzles, turbine wheel, exhaust diffuser, shaft housing, overspeed governor and reduction gearbox.

Here’s how it works: mono-fuel, introduced as a fine mist at about 200 psi into the spherical combustion chamber (called the “combustor”) is fired, with an initial combustive boost from a charge of 300 psi oxygen (from the booster bottle), by an igniter plug. In Death Wish’s case, the igniter is a conventional Prestolite AG52 spark plug fitted in the top of the combustion chamber. The spark is pulsed by an induction coil/vibrator energized from the turbo-bike’s 12-volt wet cell battery. The plug fires the combustor’s fuel charge...and keeps the show on the road.

The combustor’s hot gases (up to 2200 F) are routed by the velocityboosting exhaust torous (a scroll and nozzle ring arrangement) to twelve 0.25-in. diameter nozzles. The nozzles direct the blast of hot gas, now at supersonic velocity, against the turbine wheel’s bucket-type blades, powering the turbine wheel to an operational 70,000 rpm. Exhaust gases flow axially, exiting from the center of the turbine wheel, and are exhausted on the turbobike through a 3-in. diameter steel exhaust pipe.

The turbine wheel’s shaft, turning on four high-temperature ball bearings, drives a four-gear 16:1 reduction train which, in turn, drives a 2:1 No. 50 Diamond reduction chain and sprocket to the turbo-cycle’s rear wheel. Thus total reduction is 32:1. With the turbine wheel spinning at 70,000 rpm, the bike’s drive wheel is powered at 2187 rpm.

Gran gauges the turbine’s horsepower output from the combustor pressure gauge mounted on the turbo-cycle’s handlebar. Thus far, fuel flow has been governed to hold combustor pressure (and turbine rpm) well below rated maximums.

Says turbo-cycle designer Roy Hamilton, “Governed, we’ve been operating the turbine at a maximum 200 psi combustor pressure, roughly, about 200 bhp. By our calculations, 300 psi on the combustor gauge would signify a turbine output of about 350 bhp.”

Though governed, on one recent quarter-mile sprint the combustor pressure gauge instantaneously showed 650 psi. No damage resulted and Hamilton attributes the unusual pressure to residual fuel in the lines.

A lot of mono-fuel (and engineering sweat) has gone into Death Wish’s Turbonique engine since November 1965 when Gran and Hamilton bought it, new, for about $1500.

“Frankly,” says Hamilton, “we had a hell of a time getting that engine to run...and a considerably rougher time keeping shaft bearings in ortce she got going.”

Hamilton’s forced shaft-bearing lube system now appears to have licked the problem. At San Fernando Raceway, Death Wish went three full sprints with no apparent bearing damage. Previously, she’d sometimes broken down after a single go—roughly, after but 15 seconds or so running.

The Gran-Hamilton strategy is more conventional than their turbo-bike. That’s to “keep increasing throttle power” until, at full rated power (350 bhp) and rpm (90,000-100,000), Death Wish drags the record.

“Anything less,” flatly declares Hamilton, “simply isn’t in our plans.” [Ö]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

June 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Scene

June 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

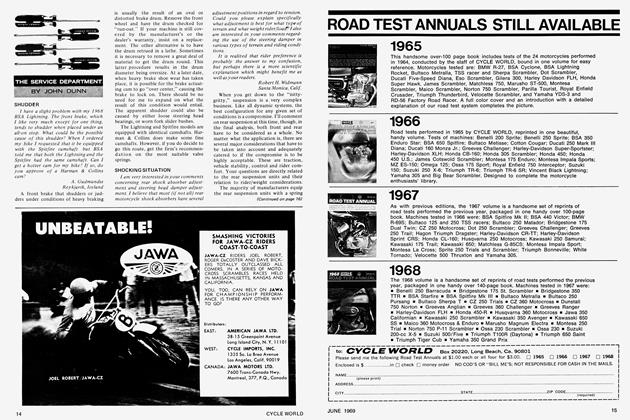

The Service Department

June 1969 By John Dunn -

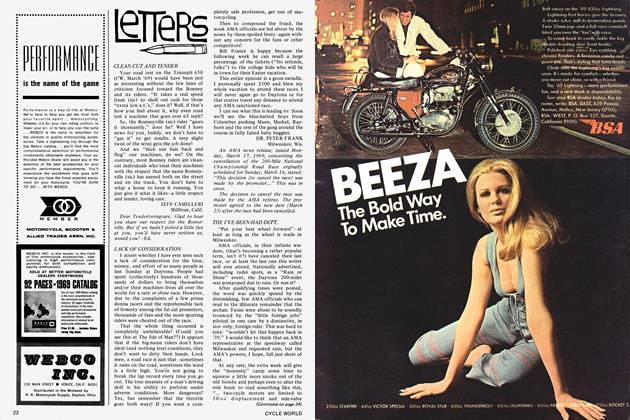

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1969 -

Legislation Forum

Legislation ForumSpecial Report: the Moving Forces Behind Motorcycle Legislation

June 1969 By J. Bradley Flippin -

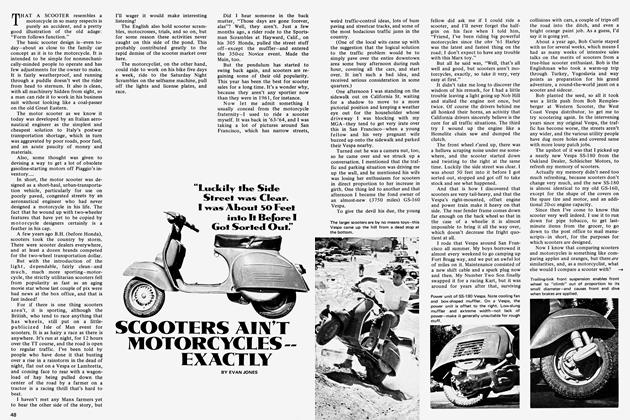

Offshoot Dept.

Offshoot Dept.Scooters Ain't Motorcycles-- Exactly

June 1969 By Evan Jones