SCOOTERS AIN'T MOTORCYCLES--EXACTLY

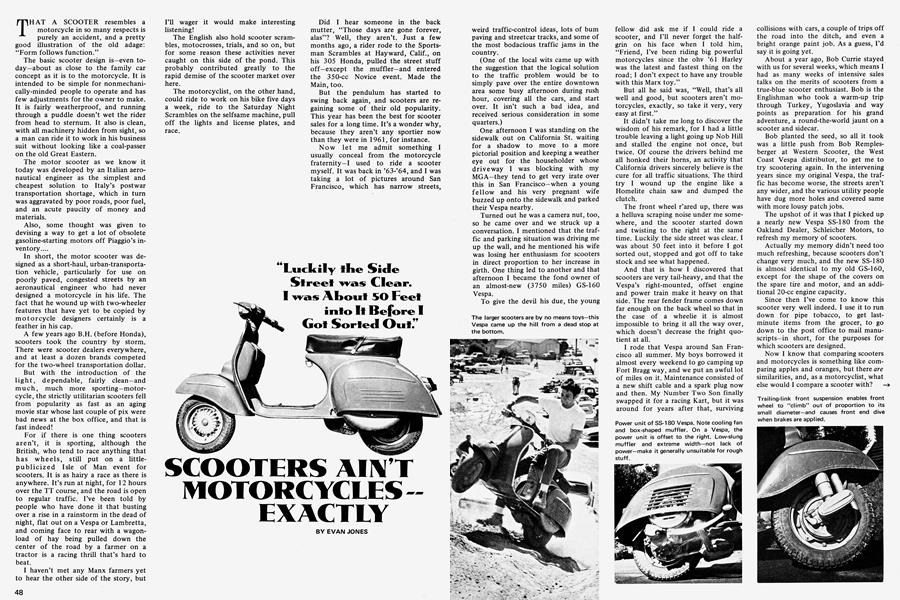

"Luckily the Side Street was Clear. I was About 5O Feet into It Before I Got Sorted out."

EVAN JONES

THAT A SCOOTER resembles a motorcycle in so many respects is purely an accident, and a pretty good illustration of the old adage: “Form follows function.”

The basic scooter design is—even today—about as close to the family car concept as it is to the motorcycle. It is intended to be simple for nonmechanically-minded people to operate and has few adjustments for the owner to make. It is fairly weatherproof, and running through a puddle doesn’t wet the rider from head to sternum. It also is clean, with all machinery hidden from sight, so a man can ride it to work in his business suit without looking like a coal-passer on the old Great Eastern.

The motor scooter as we know it today was developed by an Italian aeronautical engineer as the simplest and cheapest solution to Italy’s postwar transportation shortage, which in turn was aggravated by poor roads, poor fuel, and an acute paucity of money and materials.

Also, some thought was given to devising a way to get a lot of obsolete gasoline-starting motors off Piaggio’s inventory....

In short, the motor scooter was designed as a short-haul, urban-transportation vehicle, particularly for use on poorly paved, congested streets by an aeronautical engineer who had never designed a motorcycle in his life. The fact that he wound up with two-wheeler features that have yet to be copied by motorcycle designers certainly is a feather in his cap.

A few years ago B.H. (before Honda), scooters took the country by storm. There were scooter dealers everywhere, and at least a dozen brands competed for the two-wheel transportation dollar.

But with the introduction of the light, dependable, fairly clean—and much, much more sporting—motorcycle, the strictly utilitarian scooters fell from popularity as fast as an aging movie star whose last couple of pix were bad news at the box office, and that is fast indeed!

For if there is one thing scooters aren’t, it is sporting, although the British, who tend to race anything that has wheels, still put on a littlepublicized Isle of Man event for scooters. It is as hairy a race as there is anywhere. It’s run at night, for 12 hours over the TT course, and the road is open to regular traffic. I’ve been told by people who have done it that busting over a rise in a rainstorm in the dead of night, flat out on a Vespa or Lambretta, and coming face to rear with a wagonload of hay being pulled down the center of the road by a farmer on a tractor is a racing thrill that’s hard to beat.

I haven’t met any Manx farmers yet to hear the other side of the story, but I’ll wager it would make interesting listening!

The English also hold scooter scrambles, motocrosses, trials, and so on, but for some reason these activities never caught on this side of the pond. This probably contributed greatly to the rapid demise of the scooter market over here.

The motorcyclist, on the other hand, could ride to work on his bike five days a week, ride to the Saturday Night Scrambles on the selfsame machine, pull off the lights and license plates, and race.

Did I hear someone in the back mutter, “Those days are gone forever, alas”? Well, they aren’t. Just a few months ago, a rider rode to the Sportsman Scrambles at Hayward, Calif., on his 305 Honda, pulled the street stuff off—except the muffler—and entered the 350-cc Novice event. Made the Main, too.

But the pendulum has started to swing back again, and scooters are regaining some of their old popularity. This year has been the best for scooter sales for a long time. It’s a wonder why, because they aren’t any sportier now than they were in 1961, for instance.

Now let me admit something I usually conceal from the motorcycle fraternity—I used to ride a scooter myself. It was back in ’63-’64, and I was taking a lot of pictures around San Francisco, which has narrow streets, weird traffic-control ideas, lots of bum paving and streetcar tracks, and some of the most bodacious traffic jams in the country.

(One of the local wits came up with the suggestion that the logical solution to the traffic problem would be to simply pave over the entire downtown area some busy afternoon during rush hour, covering all the cars, and start over. It isn’t such a bad idea, and received serious consideration in some quarters.)

One afternoon I was standing on the sidewalk out on California St. waiting for a shadow to move to a more pictorial position and keeping a weather eye out for the householder whose driveway I was blocking with my MGA—they tend to get very irate over this in San Francisco-when a young fellow and his very pregnant wife buzzed up onto the sidewalk and parked their Vespa nearby.

Turned out he was a camera nut, too, so he came over and we struck up a conversation. I mentioned that the traffic and parking situation was driving me up the wall, and he mentioned his wife was losing her enthusiasm for scooters in direct proportion to her increase in girth. One thing led to another and that afternoon I became the fond owner of an almost-new (3750 miles) GS-160 Vespa.

To give the devil his due, the young fellow did ask me if I could ride a scooter, and I’ll never forget the halfgrin on his face when I told him, “Friend, I’ve been riding big powerful motorcycles since the ohv ’61 Harley was the latest and fastest thing on the road; I don’t expect to have any trouble with this Marx toy.”

But all he said was, “Well, that’s all well and good, but scooters aren’t motorcycles, exactly, so take it very, very easy at first.”

It didn’t take me long to discover the wisdom of his remark, for I had a little trouble leaving a light going up Nob Hill and stalled the engine not once, but twice. Of course the drivers behind me all honked their horns, an activity that California drivers sincerely believe is the cure for all traffic situations. The third try I wound up the engine like a Homelite chain saw and dumped the clutch.

The front wheel r’ared up, there was a helluva scraping noise under me somewhere, and the scooter started down and twisting to the right at the same time. Luckily the side street was clear. I was about 50 feet into it before I got sorted out, stopped and got off to take stock and see what happened.

And that is how I discovered that scooters are very tail-heavy, and that the Vespa’s right-mounted, offset engine and power train make it heavy on that side. The rear fender frame comes down far enough on the back wheel so that in the case of a wheelie it is almost impossible to bring it all the way over, which doesn’t decrease the fright quotient at all.

I rode that Vespa around San Francisco all summer. My boys borrowed it almost every weekend to go camping up Fort Bragg way, and we put an awful lot of miles on it. Maintenance consisted of a new shift cable and a spark plug now and then. My Number Two Son finally swapped it for a racing Kart, but it was around for years after that, surviving collisions with cars, a couple of trips off the road into the ditch, and even a bright orange paint job. As a guess, I’d say it is going yet.

About a year ago, Bob Currie stayed with us for several weeks, which means I had as many weeks of intensive sales talks on the merits of scooters from a true-blue scooter enthusiast. Bob is the Englishman who took a warm-up trip through Turkey, Yugoslavia and way points as preparation for his grand adventure, a round-the-world jaunt on a scooter and sidecar.

Bob planted the seed, so all it took was a little push from Bob Remplesberger at Western Scooter, the West Coast Vespa distributor, to get me to try scootering again. In the intervening years since my original Vespa, the traffic has become worse, the streets aren’t any wider, and the various utility people have dug more holes and covered same with more lousy patch jobs.

The upshot of it was that I picked up a nearly new Vespa SS-180 from the Oakland Dealer, Schleicher Motors, to refresh my memory of scooters.

Actually my memory didn’t need too much refreshing, because scooters don’t change very much, and the new SS-180 is almost identical to my old GS-160, except for the shape of the covers on the spare tire and motor, and an additional 20-cc engine capacity.

Since then I’ve come to know this scooter very well indeed. I use it to run down for pipe tobacco, to get lastminute items from the grocer, to go down to the post office to mail manuscripts—in short, for the purposes for which scooters are designed.

Now I know that comparing scooters and motorcycles is something like comparing apples and oranges, but there are similarities, and, as a motorcyclist, what else would I compare a scooter with?

The engine is a conventional twostroke affair, lubricated by a five-percent gas/oil mixture, and in no remote sense of the word can you call it highly-tuned. Neither can it be called temperamental. Unlike motorcycle engines of this size, it is fan-cooled, a necessity for a completely enclosed, air-cooled engine.

The carburetor air-intake is through a filter under the seat, high up out of the road dust. Filter is the dry type. For cold starting there is a conventional choke setup and the engine is cranked with a conventional foot-pedal on the right side.

There is no frame in the motorcycle sense of the word; instead, the pressed steel “body” is the frame, which means it is almost impossible to “cut down” a Vespa. And the frame forms part of the weather shielding.

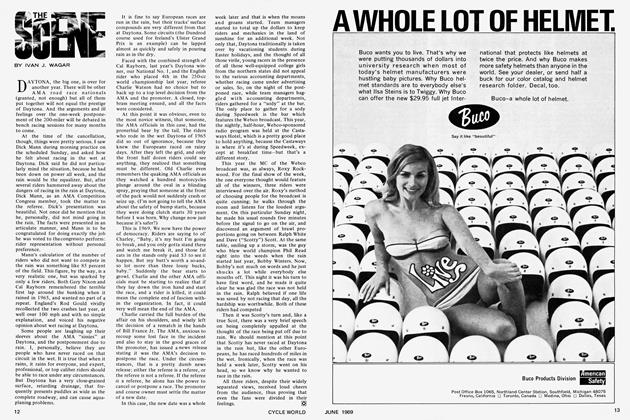

The suspension is completely different from the usual motorcycle system in that the entire engine/transmission unit pivots. In other words, the whole engine and transmission is the swing arm. The wheels are carried on automotive-type axles. This allows the wheels to be bolted to the hubs just like a fourwheeler, and makes it practical to carry a spare tire already mounted on a wheel. On a motorcycle a flat tire can be a very serious matter indeed; on a scooter it’s a temporary inconvenience.

Rear suspension is by the usual damped strut arrangement used by motorcycles, except there is only one on the Vespa instead of two, and it is extremely long, about 18 in. It is not adjustable for load. Variations in loading are taken care of by a progressivelywound spring.

The front suspension is by trailing link and another damped strut. Trailin g-link suspension enables a small wheel to climb larger bumps than would at first seem possible, but has the disadvantage of causing the machine to nosedive on application of the front brake. This is the feature that seems to bother motorcyclists most—it seems the scooter is going to tumble end over end with even a slight application of the front brake. It takes a little gettingused-to!

The nonadjustable rear and trailinglink front suspension notwithstanding, any scooter will pack like a Mexican donkey—at one time there was a craze in Europe to see just how many people could be carried on a scooter. As I recall, the record was 30 (thirty) adults!

The brakes are independent, with the rear brake operated by a foot lever sticking out of the deck. But, because scooters have a strong rear-wheel weight bias, the rear brake does a larger part of the braking than its motorcycle counterpart.

On the Vespa the brakes will easily lock up the wheels, especially the front brake. This causes no problem for the experienced rider if it happens going straight ahead, but it is very bad if it happens on a curve!

The scooter has a conventional motorcycle-type transmission, but the actuation system is different—very different. On a scooter, both the clutch and gear selector are on the left-hand grip, and the grip and clutch lever are rotated to shift gears. Once one gets used to it, it works fine, particularly starting in hilly areas, for it isn’t necessary to take first one foot off the ground and then the other to use the brake and shift gears. And it is easy to check on what gear the machine is in, for the gears—including neutral—are marked on the grip.

Steering is good, so good that no steering damper is provided, or needed, but, due to the short wheelbase, the handling is “quicker” than almost any motorcycle you can name. And there is lots of lock to enable the scooter to be maneuvered in narrow streets.

Scooters have a large frontal area due to the extensive weather shielding. This gives rise to a peculiar effect, to say the least, when meeting fast-moving trucks and busses on two-lane roads. The first time it happens causes that old feeling around the belt buckle, but once one knows what to expect, it causes no more trouble than the same thing with a motorcycle.

Scooters are quite stable due to their low center of gravity, but they won’t corner with a motorcycle because the wide deck and engine shielding grounds when a guy tries ear-’oling.

Most enthusiasts start with a stock motorcycle. From there they go on to gearing changes, hop-up jobs, different exhaust pipes, larger tires—six months after buying a bike a lot of fellows have changed them to the point where the original manufacturer wouldn’t recognize his own product.

Scooters don’t work this way. For practical purposes it is impossible to change tire sizes; the gear ratios are fixed by the manufacturer, so to change

ratios it is necessary to cut new gears, a hideously expensive way of doing business. The practical result is that a prospective purchaser of a new scooter selects a scooter to give the required performance, rather than making changes later.

For instance, a fellow or girl who intends to putt-putt around town, perhaps to solo back and forth to school or to the job, may select a little 90-cc three-speed machine, but if he intends to do a spot of touring—and there is more of this than you’d think—he’ll (or she’ll) probably go for a machine with more power.

Actually, not being able to make these changes is not such a disadvantage as it may seem, for the “comes-with” gearing, tires, and so forth on the bigger scooters are adequate for just about any purpose for which a scooter may be used.

Bob Currie, for instance, didn’t hesitate a bit about bolting a side-hack on his SS-180 to carry his luggage and, contrary to popular opinion, Englishmen don’t travel light! Bob hauls everything he can conceivably need for a two-year trip in his sidecar, plus a big battery for his rally-type lights, and has a 10-imperial gallon gas tank fabricated into the back of his legshield, to boot. And the Vespa hauls the plot without a murmur of complaint.

Recently, a young couple rode double from Peru to the United States on a Lambretta, with all their luggage, with no particular mechanical difficulties.

Tire life on scooters is rather short, due to the smallish wheels. On the other hand, many scooterists run tires till they’re thin as paper on the theory that they can get going after a flat so easily that they might as well get thenmoney’s worth out of their skins. Also, since they soon get out of the habit of taking corners hard, tread isn’t as important as on a hot motorcycle. Personally, this goes against my training, and any time I’m on two wheels I want to have a good set of tires under me. Period.

Since scooters are basically for civilized, urban transportation, they offer quite a few little niceties that usually aren’t found on motorcycles—a watertight, lockable glove compartment big enough to hold a plastic raincoat, gloves, camera, and so on. Mud and weather shielding that works. No messy machinery exposing its private parts to vulgar view. A stand that doesn’t require Charles Atlas himself to place the machine thereon. Spare tire. And as good muffling as can be fitted to a two-stroke mill. The big Vespa is the only twowheeler I’ve ever had that can sneak into our driveway without alerting the welterweight, a very definite advantage at times.

As I tell my laughing friends, “If you ain’t tried it, don’t bum-rap it.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

June 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Scene

June 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

The Service Department

June 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1969 -

Legislation Forum

Legislation ForumSpecial Report: the Moving Forces Behind Motorcycle Legislation

June 1969 By J. Bradley Flippin -

Competition

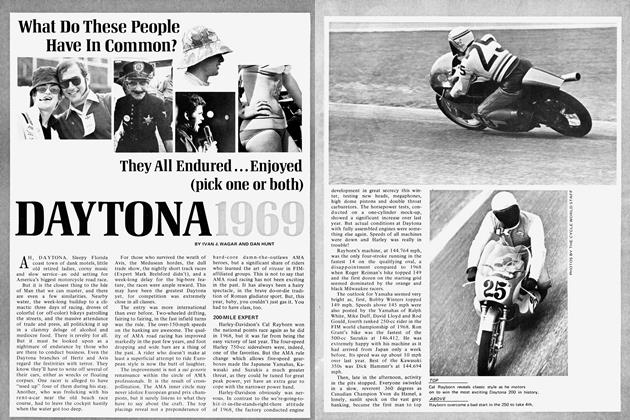

CompetitionDaytona 1969

June 1969 By Dan Hunt, Ivan J. Wagar