History of HUSQVARNA

Motocross Champion From The Land Of The Vikings

GEOFFREY WOOD

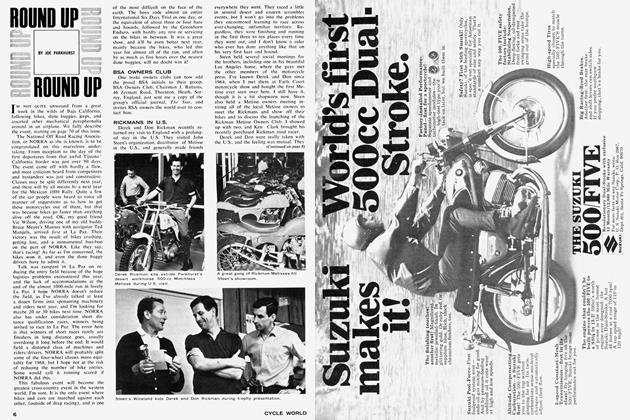

SWEDEN is A BEAUTIFUL country with its many blue lakes, deep green forests, and miles of scenic coastline. Located in the northwestern corner of Europe, it is not far from the Arctic, and, quite naturally, the climate is rather severe. With long, cold winters and large areas of rugged mountains, it would seem logical to assume that these descendents of the Vikings would have achieved little in the way of international motorcycling success.

The record, however, speaks differently, as one rather small Swedish manufacturer of motorbikes has chalked up by far the finest record ever achieved in both the European and World motocross championships. And this isn’t all, either, as the efforts of this Norse concern in the terribly competitive grand prix road racing classics during the early and middle 1930s were of great enough note to indelibly etch many a first place into the pages of history. This story of Swedish excellence in the motorbike field had its beginnings way

back in the year of 1689, when the Royal Arms Company was founded. The idea was to produce armaments for the Swedish Army, which was constantly engaged at war with somebody, and expanding sales provided the fledging company with a sound financial base. Unfortunately, Carl XII decided to have a go at Russia, and even though production reached new heights while the battle was on, a sharp depression hit the company when Russia won.

For many years after, the concern just managed to keep its financial head above water. In 1867 matters finally turned for the better when Erik Dahlberg reorganized the company under the name that is still used today — Husqvarna Vapenfabriks AB. Then followed more wars and the new company prospered, but then, after the Franco-Prussian war in the early 1870s, the demand for muskets once again dropped off.

This time the company management decided to branch out into other products that would meet more peaceful needs. The move proved to be a wise one as Sweden at last entered a more peaceful era, and sewing machines were soon rolling off the production line. Production of these domestic items has continued, and today Husqvarna is famous for its household appliances, timber saws, fine guns, sewing machines, lawn mowers and furnaces.

The most important item that Husqvarna has ever produced, at least to the world’s motorsportsmen, is none of the above products, though. For to the aficionado of fine motorbikes the mention of Husqvarna means just one thing — fabulous motocross machines that have garnered a total of seven European and world championships.

The story of this modern day terror of rough-stuff competition began in 1903, when the industrial revolution was making itself felt in Sweden. In that year the factory produced its first motorbike — an orthodox 1-1/4-hp single-cylinder, beltdriven mount with caliper type brakes on the wheel rims. The engine was a Belgianmade FN, and bicycle pedaling gear was used for starting and on hills. The singlespeed Husqvarna proved to be a reliable method of transport, and the reputation of the company was established.

During those early years of the motorcycle the Husqvarna tried what most other European factories did — experiment to find a sound design. This experimentation finally led to a Husqvarna bicycle with a Swiss made Moto-Reve engine, and the plot proved to be a great deal faster and more reliable than anything that they had previously produced.

The engine was a 500cc V-twin, and it drove the bicycle through a single-speed belt. There were pedals for starting, and a caliper type brake was used on the rear wheel. The Moto-Reve engine was available in 2-1/2 and 4 horsepower, so the performance was considerably quicker than the first Husqvarna single.

The next big step forward came in 1916, when Husqvarna designed and produced their own engine. This new “Husky” was rather advanced for its day, and it went a long way in establishing their name all over Scandinavia. The powerplant was a 50-degree V-twin with bore and stroke measurements of 65 x 83mm. The 550cc engine featured side valves, and the cylinders and head were both cast iron. The output of 11 hp was transmitted through a three-speed gearbox, and gear shifting was by a hand shift on the right side of the fuel tank. Both the primary and final

drives were by roller chain, and the clutch lever was operated by the left hand.

The frame used was the rigid type, and the only method of suspension was by the coil springs in the girder front fork. A “vintage” era gas tank was mounted between the two top frame tubes, and only one caliper brake was used on the rear wheel. The oil was pumped to the engine by a hand pump that built up pressure in the lubrication system, and a single carburetor fed both cylinders.

This side-valve twin formed the basis of the Husqvarna production during the 1920s, and the model was subsequently improved by adopting such features as internal expanding brakes, improved lubrication, a greater engine output, and a better electrical system.

By 1930 another engine type was setting the world on fire, though, and this was the overhead valve engine with its superior performance. The Husqvarna engineers were quick to accept this modern trend, and the 1930 sales brochure well illustrated this policy with five of the ten models listed having ohv powerplants. Carl Heimdal was the chief designer and engineer at that time, and his machines reflected his brilliance even if the Husqvarna was still little known outside of the Scandinavian countries.

The lowest priced Husqvarna that year was the model No. 25, a side-valve 175cc mount that provided reliable day-to-day transportation. The little engine had a bore and stroke of 60 x 62mm, and it developed 5.5 hp. A three-speed hand shift gearbox with ratios of 8.3, 12.6, and 23.2 to 1 was used, and the drive was by roller chain. As was common in those days, a

girder front fork and rigid frame were featured, and the only brake was an internal expanding unit on the rear wheel.

Next in the catalog was model No. 30, a 250cc side-valver that produced 7.5 hp. Engine measurements were 64.5 x 76mm, and gear ratios were 6.9, 10.5, and 19.3 to 1. The 250 was similar to the 175cc model except that it had a front brake and a more refined accessory list.

For the customer who wanted even more performance in the side-valve design there was the No. 50-S model — a 550cc job that developed 14 reliable horsepower. The 50-S had a bore and stroke of 79 x 101mm, and the gearbox had ratios of 5.3, 9.0, and 14.1 to 1.

The final side-valve single listed in the catalog was the No. 61 model. This machine had a 600cc engine that produced 16 hp, and the bore and stroke were 86.8 x 101mm. This model was produced with a touring type sidecar only, and the beefy torque from the powerplant was ideally suited for the task.

For the more discriminating owner the factory produced the model No. 190 — a side-valve 550cc V-twin that developed 15 hp. The bore and stroke were 65 x 83mm, and the gear ratios were 5.3, 7.9, and 14.1 to 1. The twin was known as an exceptionally smooth and reliable mount, and it was very popular with the Swedish riders of the day.

In the early 1930s the Swedish riders, like most all European enthusiasts, became more performance conscious, and to meet this demand the factory produced a range of overhead valve singles. The first was the No. 30-A, a 250cc model that developed 11 hp on its 5.6 to 1 compression ratio. The bore and stroke were 65.5 x 80mm, and internal expanding brakes were fitted to both wheels.

Then there was the No. 50 “Turistmodel,” a 500cc job that developed 20 hp. The big single had measurements of 85.7 x 85mm, and the gear ratios were the same as the 500cc side-valve model. Both wheels had hefty internal expanding brakes, and a girder front fork was used with a rigid frame.

The two models that really made Swedish pulses pound were the models No. 50-A and 50-B. Called the “SportmodeH” and “Super SportmodeH.” These two bikes were for the fellow who wanted the very best in Swedish design and performance. Both machines were similar to the “Turistmodell” except that modifications to the cams, valves and carburetors boosted the power output to 25 at 4,600 rpm and 30 at 5,800 rpm respectively. The wheelbase on these 70and 85-mph speedsters was 55.6 inches, and the dry weight was 363 pounds. The muffler fitted was a large “Brooklands” type, and the healthy exhaust note announced that a mighty rapid motorbike was coming down the road.

The last page of the 1930 catalog listed a very specialized machine for its day — the 500cc “Specialracer Motorcykel.” This ohv thumper was built for the man who wanted to çompete in the long distance cross-country races that were so popular in the Scandinavian countries in those days. A lightweight rigid frame was used along with an open exhaust, and the engine developed the remarkable output of 33 hp. These old Swedish cross-country races were actually a long distance scrambles, and the speedy and rugged 30-inch single chalked up an enviable record in these events.

The Husqvarna range continued to expand during the 1930s as the industrial revolution gradually put people on wheels. In 1931 a new 350cc side-valve model was added to the stable, and this 9 hp model had a bore and stroke of 71 x 88mm. The 4,000 rpm side-valver was followed up in 1932 by an ohv model that developed 14 hp at 4,500 rpm.

During the middle 1930s the affluency of the Swedish people was on the increase, so it was only logical that Husqvarna would add a luxury class machine to their range. Called the “Modell 120,” the new mount was a 990cc V-twin introduced in 1933. The side-valve powerplant had measurements of 79 x 101mm, and its 26 hp was produced at 3,500 rpm. The gear ratios were 4.10, 6.35, and 10.1 to 1, and the big twin was noted for its mile-eating lope. The wheelbase was rather long at

58.8 inches and the dry weight was 429 pounds. The “120” model was a very finely finished machine, and it was truly one of the world’s most elegant motorcycles in its day.

The following year a new 500cc ohv model replaced the earlier versions. This machine was uniquely destined many years later to make its mark in international competition. Named the “Modell 110 TV,” the new powerplant had measurements of 79 x 101mm. Maximum power was 22 at 4,200 rpm, and the pushrod engine had an outward similarity to the old British Ariel. The gearbox was also a new fourspeeder, with ratios of 4.8, 6.0, 8.1, and

12.8 to 1.

This new “Husky” was a more attractive bike than the previous ohv models, and such things as totally enclosed valve springs helped make the bike run much cleaner. The whole range of Husqvarnas was improved in detail during the next few years, and they became known as exceptionally well designed motorbikes.

In 1936 the catalog listed a total of five models. First was the 350cc side-valve single that produced 9 hp at 4,000 rpm. Next was its ohv stablemate that developed 14 hp at 4,500 rpm. Then came the 15 hp sidevalve 500cc that turned to 4,200 rpm, and the last single was the 500cc ohv that churned out 24 hp at 4,800 rpm. These singles all featured a rigid frame, girder front fork, good brakes, and the traditional white fuel tank with the painted on emblem. The 500cc ohv model was packing a top gear ratio of 4.55 to 1, which provided the respectable speed of 80 mph.

The last model in the lineup that year was the big 990cc side-valve V-twin. The twin could be had with several types of sidecars for both touring and commercial purposes; and it proved popular with the Swedish riders.

After 1936 the policy at the company took a different direction, and the singles and big V-twin were dropped from production. Maybe it was the long cold winters combining with increased income levels that put people into cars or maybe it was the rugged sales competition from England. but at any rate, the factory switched over to producing lightweight models. These new, inexpensive two-strokes were produced up until the war, and they did prove popular with the Swedes.

And so ended the pre-war story of Husqvarna’s motorcycle production. But it certainly is not the whole story of the marque during those early years. It could be said, and rightfully so, that Husqvarna’s bikes were not quite good enough to compete in the rough and tumble worldwide market place, and they failed to make a really significant impact on the international motorcycle scene. There was, however, a chapter in the company’s story that did make a notable impression in the history books, and that was their participation in the colorful road racing classics of the day.

(Continued on page 81)

The competition record of Husqvarna can be divided into two distinctive efforts — the pre-war grand prix chapter and the post-war motocross chapter. Of these two, the post-war effort has been by far the most successful. But for pure exotic machinery in a colorful setting, it is hard to beat the days of the grand prix Husky.

The story of their road racing days began in 1930 when Folke Mannerstedt came back from Belgium, where he had been employed by the FN concern. Folke was hired to design a road racing bike, as the factory had decided that the best way to gain international publicity was to win races. The idea was to field a works team on bikes that could win, even if the company’s sales figure was not high enough to expend as much on racing as some of the larger European factories.

Mannerstedt went right to work, and by late summer of 1930 he had a team ready for the Swedish Grand Prix. The racers were beautiful bikes, too, but they proved to be too slow and unreliable to hold off the all-conquering Nortons. The basic layout of the 500cc Husqvarna was a pushrod operated overhead valve V-twin engine mounted in a rigid frame with a girder front fork. It was obvious that more development work would be needed to make the twin a race winner, and so back to the shop it went.

In the spring of 1931, an improved GP machine made its appearance, and that year saw an amazingly good record chalked up in minor grand prix events all over Sweden, Denmark, and Norway. In the classical Swedish Grand Prix, the team again saw Jimmy Simpson streak away on his Norton single, and once again, Folke was faced with raising more horsepower.

During the long, dark Arctic winter the lights glowed very late in the race shop, as more performance was sought from the twin. By summer Ingenjor Mannerstedt was certain that he had a winner and that his bikes could conquer the “unconquerable” Nortons. The famous British ohc single, however, had won all eight of the 1931 grands prix, plus taking the first three places in the 1932 Senior TT, so it was certainly an impressive champion.

When the flag dropped for the 1932 Swedish GP it was obvious to the crowd that Husqvarna had a potential winner in their twin, as Ragnar Sunnqvist and Jimmy Simpson locked themselves in a titanic battle. Lap after lap they fought it out, with Ragnar finally scratching over the line first. Like wildfire the news spread over Europe that this upstart Swedish factory had trounced the mighty Norton. Mannerstedt, meanwhile, quietly went back to his shop to further improve his twin, for he well knew that next year Norton would be out for blood.

(Continued on page 82)

The following year the Swedish Grand Prix was given the title of “Grand Prix d’ Europe,” a recognition that was given in the pre-war days to one of the season’s races to signify that it was the premier event of all the classics. Quite naturally, all the great racing names of Europe entered the 1933 race, and the tiny Swedish company obviously had the supreme challenge on their hands.

The race proved to be a real thriller, with the works Norton team of Stanley Woods and Tim Hunt holding off the home-country twins. Towards the end of the race, Hunt crashed and Sunnqvist closed on Woods. Then Stanley’s engine blew and Ragnar looked like a sure winner. Fate held the cards differently, though, as Ragnar’s bike lost its chain only one lap from the finish, and his teammate. Gunnar Kalen, romped home the victor.

After such a splendid showing the factory management decided to make a bid for the European Championship in 1934, and Stanley Woods (Ireland) and Ernie Nott (England) joined with Sunnqvist and Kalen to make a truly formidable team. The team planned on contesting most of the classical races of the day, and Mannerstedt even built a 350cc twin with which to enter the Junior class races.

By then the 50Qcc twin had become an exceptionally rapid machine, and the British press eagerly “discussed” it when it arrived in the Isle of Man for the TT race. The bore and stroke were 65 x 75mm, and the compression ratio varied from 9.0 to 10.0 to 1, depending on the fuel. The powerplant produced 44 hp at 6,800 rpm, which was as good as anyone was getting in those days. The engine breathed through two 1-inch Amal TT carburetors, and the hairpin valvesprings were left exposed for cooling. The twin was surprisingly light at 297 pounds, and the wheelbase was rather short at 52.0 inches. Aluminum alloy was used for the heads, cylinders, and fuel and oil tanks.

The team fared quite well that year, with Nott starting off with a third place in the Junior TT. Stanley was running a strong second in the Senior TT when he ran out of fuel only a few miles from the finish, but he did turn the fastest lap of the race at 80.49 mph. At home, in the Swedish event, Ragnar Sunnqvist once again trounced the field, and there were a few “places” gained in the other continental events.

In 1935 the marque scored only one victory, when Stanley Woods rode the 500cc twin to a win in the Swedish Grand Prix. About the only Junior Class success was the ninth place of Helge Carlsson in the Grand Prix d’ Europe in Ireland, and then the marque lost its interest in road racing. The European grand prix scene became intensely competitive during the last 1930s, and it took either government financial backing or a large sales volume to finance a serious racing campaign. Husqvarna had neither, so they bowed out. While it is true that the marque never established a really great record of wins, they nevertheless did add the nostalgia of exotic machines in exciting races that make for an interesting chapter in our sport.

After the war, the factory produced 98 and 1 18cc two-strokes for the home market, followed by a 175cc “sport” model in the early 1950s. This later model was immediately modified for scrambles competition by the Swedish riders when motocross racing became popular in Sweden, and this has led to the current situation where all the company produces are 250 and 350-360cc road racing and motocross machines. This rough-stuff racing ushered in the second great era of the company, and for this we have to go back to 1958.

In the middle 1950s, motocross racing became tremendously popular in Europe, and many factories began developing some highly sophisticated machines for their works riders to race. The FIM established a series of races to count for the 500cc European Championship in 1952, and in

1957 the sport was elevated to full World Championship status. This was followed by a special Coupe d’ Europe award in

1958 for 250cc machines, and then this elevated to World Championship status in 1962.

The Husqvarna factory first became interested in this rugged sport in 1958 when Rolf Tibblin was entered in several rounds of the 250cc class. Rolf’s bike was a twostroke, and it performed well and thus encouraged the company to make a more determined bid in 1959.

The motocross bike underwent a great deal of development work during the winter. Then, by spring, a really fine mount was rolled out of the shop. The

1959 works bike has since been improved and put into production, and it has become one of the most successful scramblers ever developed. The single-port, two-stroke engine was orthodox but very rugged, and the light 200 pound weight set a new fashion in the motocross sport. On this 250, Tibblin easily won the Coupe d’ Europe trophy, and other Husqvarna riders took fifth and sixth in the championship standings. The post-war chapter of Husqvarna was on its way!

During the long winter, factory managers made a momentous decision to compete in the 500cc class and sponsor a team of riders. This move was thought by many to be absurd, because the marque had not produced a 500cc engine since 1936, and motocross racing had become a very competitive sport. So the world sat back to wait and see what the Swedish company would come up with, while the factory engineers got down to the task of designing the bike.

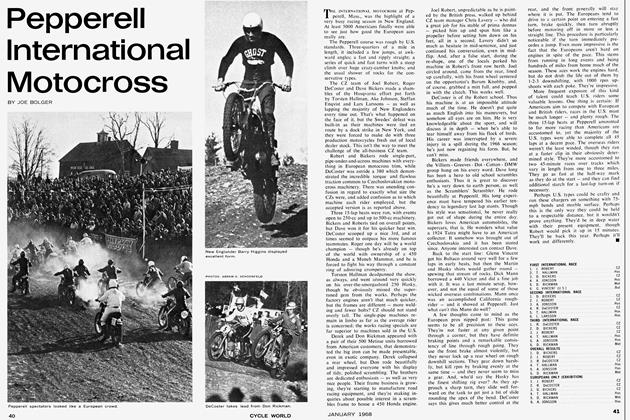

In the spring of 1960 the new Husqvarnas made their debut — and what beautiful machines they were. The frame was a double loop cradle type with an Italian Ceriani front fork. The gearbox and rear wheel were from the British AJS 7R road racer, and Girling shocks were fitted to the rear swinging-arm. The choice of a powerplant was the really surprising item, though, as the factory chose the old 1934 pushrod single! The ancient thumper was updated by fitting a Lucas racing magneto, casting the cylinder and head in alloy, using different cams, valves, and pis ton, and shortening the stroke to 99mm from the original 101 figure. The engine produced 35 hp, combined with great gobs of torque in the middle rpm range. With this bike the pride of Sweden hoped to capture the world title - even if the en gine was 26 years old!

(Continued on page 84)

IIIc w~j~ u y~ai 1Iu~ The works team consisted of Bill Nils son, Sten Lundin, and Roif Tibblin; and the smiles on the faces of the critics regard ing the antiquity of those engines was soon wiped off - fast! By season's end, the team had quite literally clobbered the competition, with Nilsson crowned cham pion, Lundin in second and Tibblin in fourth. Apart from the superb handling of these big singles, the `experts" attrib uted their success to the light 312-pound weight - a pleasant contrast to the cum bersome 370-pound weight of the popular BSA Gold Star.

In 1961 the big singles battled all sea son long with ex-teammate Sten Lundin and his Swedish-built Lito; but in the end, the Lito won, with Nilsson in second and Tibblin in fifth positions. The 250 two stroke faired even worse, with Torsten Hailman gaining a fourth place in the title chase. In 1960 the little Huskys had taken fourth and sixth places, so the em phasis on the larger class had definitely hurt the marque's chances in the Coupe d' Fii t'~,ne

r~ui ope. For 1962 the factory made a determined effort in both classes. Their main riders that year were the experienced Roif Tib bun in the Senior class and the young but promising Torsten Hallman in the 250 class. During the summer season these two Vikings literally flew through the air, and in the end, both were crowned Champion of the World. Then, just to prove that 1962 was the real thing, these same two riders once again won the two world mo tecross titles. This record is truly remark able, for it is the only time that a make has won both classes in one year - let alone two years in a row!

After those two magnificent years, the factory lost interest in the 500cc class and concentrated on only the lightweight events. However, during 1964 and 1965 the Czechoslovakian-built CZ had a fabu lous string of successes, and the Husqvarna was generally pushed into lesser positions. During 1966 the marque made a fabu lous comeback, with Torsten dominating the 250cc motocross classic all season long. In capturing the 1966 title, Torsten has achieved what no other rider has ever accomplished - win three World moto cross championships. But, then, this sort of record is nothing new at Husqvarna, for RoIf Tibblin is the only man to ever win both the 250 and 500cc titles.

And so ends this story of the Hu~ qvarna; a truly remarkable motorbike from the land of the Vikings. While it is true that their products have never been really prominent in the world market, they nev ertheless have added two of the most col orful chapters to the history of motorcycle sport. From the intriguing V-twin grand prix bikes of the 1930s to the post-war motocross singles - this is a story that is rich in color and tradition.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue