Pepperell International Motocross

JOE BOLGER

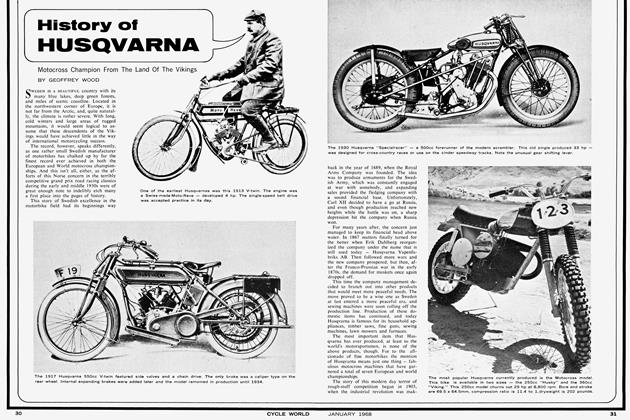

THE INTERNATIONAL MOTOCROSS at Pepperell, Mass., was the highlight of a very busy racing season in New England. At least 5000 Americans finally were able to see just how good the European aces really are.

The Pepperell course was rough by U.S. standards. Three-quarters of a mile in length, it included a few jumps, at awkward angles; a fast and ripply straight; a series of quick and fast turns with a steep climb over huge crazy-camber knobs; and the usual shower of rocks for the conservative types.

The CZ team of Joel Robert, Roger DeCoster and Dave Bickers made a shambles of the Husqvarna effort put forth by Torsten Hallman, Ake Johnson, Steffan Enqvist and Lars Larssons — as well as lapping the majority of New Englanders every time out. That’s what happened on the face of it, but the Swedes’ defeat was built-in as their machines were tied en route by a dock strike in New York, and they were forced to make do with three production motorcycles fresh out of local dealer stock. This isn’t the way to meet the challenge of the all-business CZ team.

Robert and Bickers rode single-port, pipe-under-and-across machines with everything in European motocross trim, while DeCoster was astride a 380 which demonstrated the incredible torque and flawless traction common to Czechoslovakian motocross machinery. There was unending confusion in regard to exactly what size the CZs were, and added confusion as to which machine each rider employed, but the accepted version is as reported above.

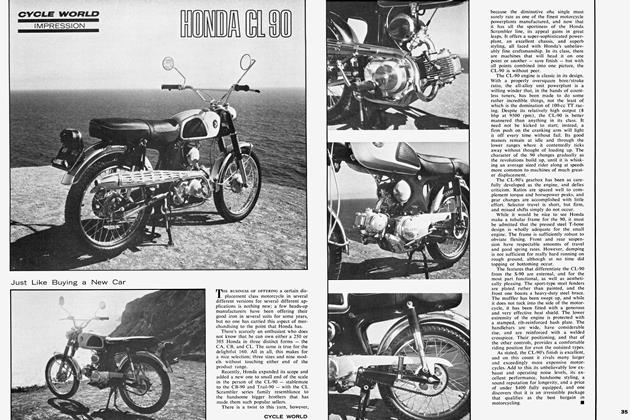

Three 15-lap heats were run, with events open to 250-cc and up to 500-cc machinery. Bickers and Roberts tied on overall points, but Dave won it for his quicker heat win. DeCoster scooped up a nice 3rd, and at times seemed to outpace his more famous teammates. Roger one day will be a world champion — though he's already on top of the world with ownership of a 450 Honda and a Munch Mammut, and he is forced to fight his way through a constant ring of admiring crumpetry.

Torsten Hallman deadpanned the show, as always, and went around very quickly on his over-the-smorgasbord 250 Husky, though he obviously missed the supertuned gem from the works. Perhaps the factory engines aren’t that much quicker, but the frames are different — more welding and fewer bolts? CZ should not stand overly tall. The single-pipe machines remain in limbo as far as the average rider is concerned; the works racing specials are far superior to machines sold in the U.S.

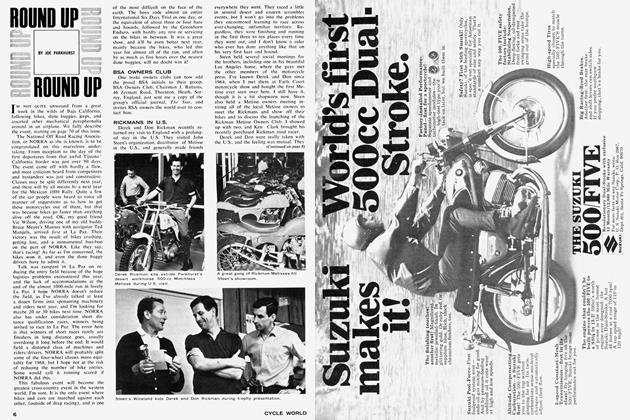

Derek and Don Rickman appeared with a pair of their 500 Metisse units borrowed from American customers, that demonstrated the big iron can be made presentable, even in exotic company. Derek collapsed a rear wheel, but Don rode beautifully and impressed everyone with his display of tidy, polished scrambling. The brothers are dedicated enthusiasts — as well as very nice people. Their frame business is growing, they’re starting to manufacture road racing equipment, and they’re making inquiries about possible interest in a scrambles frame to house a 450 Honda engine.

Joel Robert, unpredictable as he is painted by the British press, walked up behind CZ team manager Chris Lavery — who did a great job for his stable of prima donnas — picked him up and spun him like a propeller before setting him down on his feet, all in a second. Lavery didn’t so much as hesitate in mid-sentence, and just continued his conversation, even in midflip. And, after a false start, during the re-shape, one of the locals parked his machine in Robert’s front row berth. Joel circled around, came from the rear, lined up carefully, with his front wheel centered on the opportunist’s Barum Knobby, and, of course, grabbed a mitt full, and popped in with the clutch. This works well.

DeCoster is of the Robert school. Thus his machine is at an impossible attitude much of the time. He doesn’t put quite as much English into his maneuvers, but somehow all eyes are on him. He is very knowledgeable about the sport, and will discuss it in depth — when he’s able to tear himself away from his flock of birds. His career was interrupted by a severe injury in a spill during the 1966 season; he’s just now regaining his form. But, he can’t miss.

Bickers made friends everywhere, and the Villiers - Greeves - Dot - Cotton - DMW group hung on his every word. Dave long has been a hero to old school scrambles enthusiasts. Thus it is great to discover he’s a very down to earth person, as well as the Scramblers’ Scrambler. He rode beautifully at Pepperell. His long experience must have tempered his earlier tendency to legendary last lap stunts. Though his style was sensational, he never really got out of shape during the entire day. Bickers loves American automobiles, the supercars, that is. He wonders what value a 1924 Tatra might have to an American collector. It somehow was brought out of Czechoslovakia and it has been stored since. Anyone interested can contact Dave.

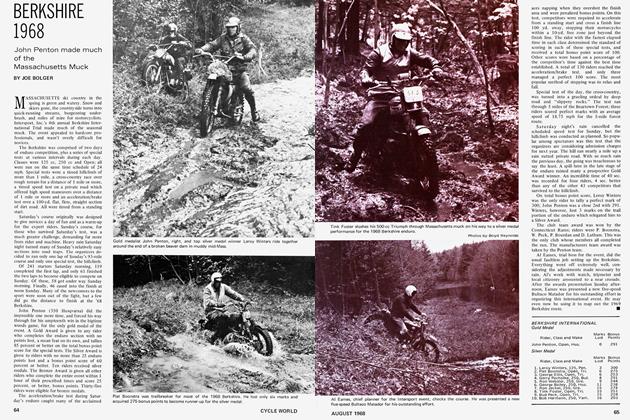

Back to the start line: Glenn Vincent got his Bultaco around very well for a few laps in early heats, but then the Martin and Husky shirts would gather round — spewing that stream of rocks. Dick Mann borrowed a 440 Victor and did a fine job with it. It was a last minute setup, however, and not the equal of some of those wicked overseas combinations. Mann once was an accomplished California roughrider — and it showed at Pepperell. Just what can’t this Mann do well?

A few thoughts came to mind as the European pros nipped past: This game seems to be all precision to these aces. They’re not faster at any given point through a corner, but they have definite braking points and a remarkable consistency of line through rough going. They use the front brake almost violently, but they never lock up a rear wheel on rough downhill sections. They gear down harshly, but kill rpm by braking evenly at the same time - and they never seem to miss a gear. And, who’d say the Husky has the finest shifting rig ever? As they approach a sharp turn, they slide well forward on the tank to get just a bit of slide rounding the apex of the bend. DeCoster says this gives much better control at the

rear, and the front generally will stay where it is put. The Europeans tend to drive to a certain point on entering a fast turn, brake quickly, then turn abruptly before motoring off in more or less a straight line. This procedure is particularly noticeable if the turn immediately precedes a jump. Even more impressive is the fact that the Europeans aren't hard on engines in spite of the pace. This stems from running in long events and being hundreds of miles from home much of the season. These aces work the engines hard, but do not drub the life out of them by 1-2-3 downshifting, with 1000 rpm upshoots with each poke. They're impressive.

More frequent exposure of this kind of talent could teach U.S. riders some valuable lessons. One thing is certain: If Americans aim to compete with European and British riders, races in the U.S. must be much longer - and plenty rough. The three 15-lap heats at Pepperell amounted to far more racing than Americans are accustomed to, yet the majority of the U.S. types were able to complete all 45 laps at a decent pace. The overseas riders weren’t the least winded, though they ran at a faster clip in their obviously determined style. They’re more accustomed to two 45-minute races over tracks which vary in length from one to three miles. They go as fast at the half-way mark as they do at the start — and they can find additional starch for a last-lap turn-on if necessary.

Perhaps U.S. types could be crafty and run these chargers on something with 75mph bends and marble surface. Perhaps this is the only way they could be held to a respectable distance, but it wouldn't prove anything. They’d be in deep water with their present equipment, though Robert would pick it up in 15 minutes. They’ll be back this year. Perhaps it’ll work out differently.