HARLEY-DAVIDSON SPRINT CRS

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

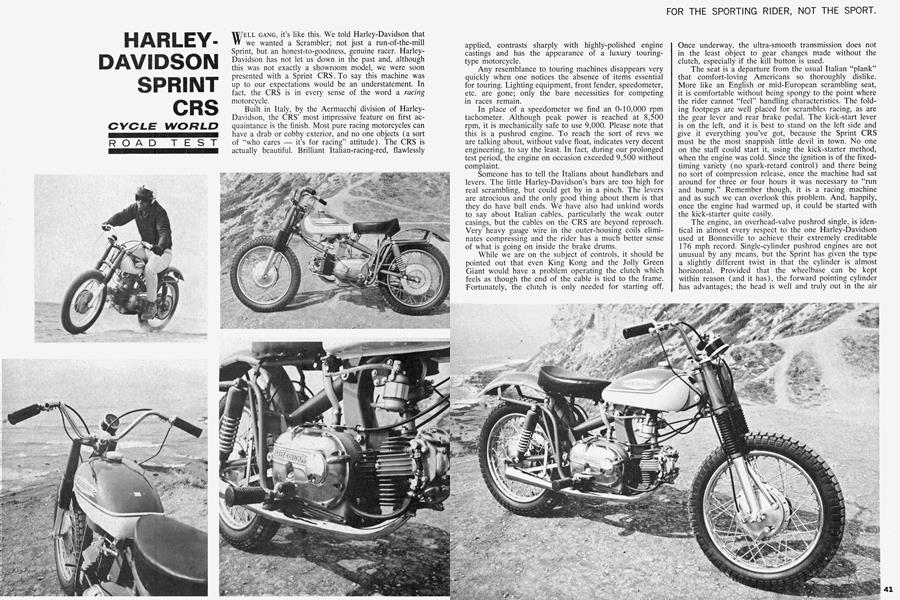

WELL GANG, it's like this. We told Har1ey-Davidson that we wanted a Scrambler; not just a run-of-the-mill Sprint, but an honest-to-goodness, genuine racer. HarleyDavidson has not let us down in the past and, although this was not exactly a showroom model, we were soon presented with a Sprint CRS. To say this machine was up to our expectations would be an understatement. In fact, the CRS is in every sense of the word a racing motorcycle.

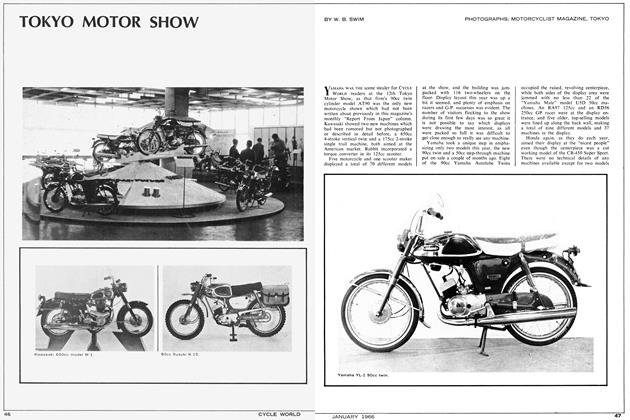

Built in Italy, by the Aermacchi division of HarleyDavidson, the CRS’ most impressive feature on first acquaintance is the finish. Most pure racing motorcycles can have a drab or cobby exterior, and no one objects (a sort of “who cares — it’s for racing” attitude). The CRS is actually beautiful. Brilliant Italian-racing-red, flawlessly applied, contrasts sharply with highly-polished engine castings and has the appearance of a luxury touringtype motorcycle.

Any resemblance to touring machines disappears very quickly when one notices the absence of items essential for touring. Lighting equipment, front fender, speedometer, etc. are gone; only the bare necessities for competing in races remain.

In place of a speedometer we find an 0-10,000 rpm tachometer. Although peak power is reached at 8,500 rpm, it is mechanically safe to use 9,000. Please note that this is a pushrod engine. To reach the sort of revs we are talking about, without valve float, indicates very decent engineering, to say the least. In fact, during our prolonged test period, the engine on occasion exceeded 9,500 without complaint.

Someone has to tell the Italians about handlebars and levers. The little Harley-Davidson’s bars are too high for real scrambling, but could get by in a pinch. The levers are atrocious and the only good thing about them is that they do have ball ends. We have also had unkind words to say about Italian cables, particularly the weak outer casings, but the cables on the CRS are beyond reproach. Very heavy gauge wire in the outer-housing coils eliminates compressing and the rider has a much better sense of what is going on inside the brake drums.

While we are on the subject of controls, it should be pointed out that even King Kong and the Jolly Green Giant would have a problem operating the clutch which feels as though the end of the cable is tied to the frame. Fortunately, the clutch is only needed for starting off.

Once underway, the ultra-smooth transmission does not in the least object to gear changes made without the clutch, especially if the kill button is used.

The seat is a departure from the usual Italian “plank” that comfort-loving Americans so thoroughly dislike. More like an English or mid-European scrambling seat, it is comfortable without being spongy to the point where the rider cannot “feel” handling characteristics. The folding footpegs are well placed for scrambles racing, as are the gear lever and rear brake pedal. The kick-start lever is on the left, and it is best to stand on the left side and give it everything you’ve got, because the Sprint CRS must be the most snappish little devil in town. No one on the staff could start it, using the kick-starter method, when the engine was cold. Since the ignition is of the fixedtiming variety (no spark-retard control) and there being no sort of compression release, once the machine had sat around for three or four hours it was necessary to “run and bump.” Remember though, it is a racing machine and as such we can overlook this problem. And, happily, once the engine had warmed up, it could be started with the kick-starter quite easily.

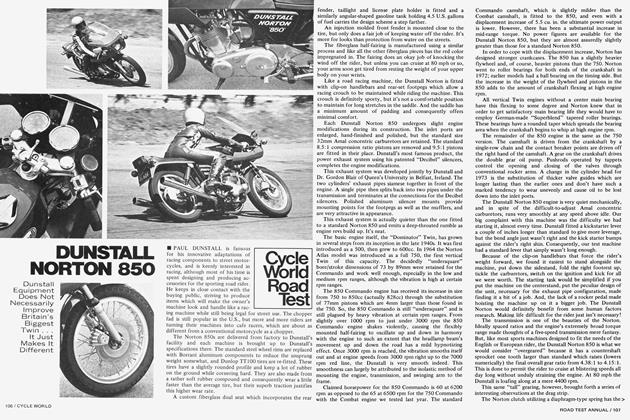

The engine, an overhead-valve pushrod single, is identical in almost every respect to the one Harley-Davidson used at Bonneville to achieve their extremely creditable 176 mph record. Single-cylinder pushrod engines are not unusual by any means, but the Sprint has given the type a slightly different twist in that the cylinder is almost horizontal. Provided that the wheelbase can be kept within reason (and it has), the forward pointing cylinder has advantages; the head is well and truly out in the air stream, which leads to nice, even head cooling. One other bonus is that the center of gravity is low, a worthwhile consideration.

Maintenance on the cylinder head and its associated parts is fabricated by the horizontal layout. We saw the tappets being checked and it was much easier than fumbling around up under a gas tank or frame member. Spark plug removal and replacement is even simpler than with the more conventional upright design.

The pushrods have their tunnel cast into the cylinder and cylinder head, and are nicely hidden away. However, the valve gear oil on the Sprint CRS is fed through external neoprene lines leading to “banjo” fittings on the intake and exhaust rocker shafts. This oil must drain back to the sump and gravity being what it is, the drain must be from the lowest part of the rocker box. This results in a very vulnerable metal tube leading from the exhaust rocker box to the sump directly under the engine. It is surprising that the maker does not use a crash guard of some sort under the engine, especially on this racing version.

The carburetor is on a very steep downdraft angle; in fact almost vertical. Even more than on standard Sprint models. The carburetor bell goes into an extremely effective looking paper-element air cleaner, which is hidden by a small metal guard protruding from the bottom of the gas tank. Unusual for a dirt machine, the exhaust pipe is mounted low rather than upswept. It is, however, tucked in close to the engine and thus provides a very respectable ground clearance.

The CRS frame follows the standard Sprint arrangement, consisting of a healthy 2-3/8" straight back-bone tube, extending from the steering head back behind and above the gearbox. At this point a well-gussetted junction meets a pair of tubes that start under the gearbox and loop up and rearward to serve as rear damper unit and rear fender mounts. The swing arm is mounted inside these frame members and makes a very sturdy rear section.

Actually the machine is quite heavy, weighing 265 pounds wet, and we spotted some places where weight could be saved; the rear fender, for instance, is made of steel. However, the CRS does not feel heavy when being ridden, and this may be attributed to the low center of gravity.

Suspension was too stiff at first, but as we gradually put rough miles on the machine we were pleased to find that it did get much smoother. After 250 miles in the rough, suspension became one of the better features. Front fork travel appeared to be adequate. Jumping and thumping along a favorite riverbed did not prove otherwise.

Although the CRS is a moderate to good scrambler, we rather imagine that it would be more at home on a halfmile flattrack or in TT scrambling. With the seat mounted somewhat more forward than most scramblers, and with higher than standard handlebars, it would be right in its glory at Ascot. In terms of pure speed on smooth, fast, hard surfaces, the CRS was a definite match for a 500cc machine we had taken along for kicks.

HARLEY-DAVIDSON SPRINT CRS

$855