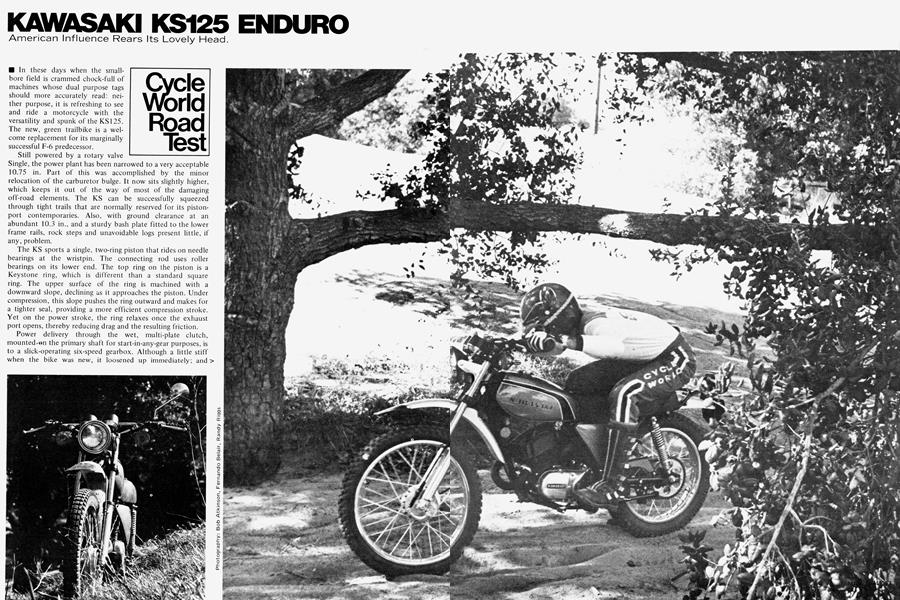

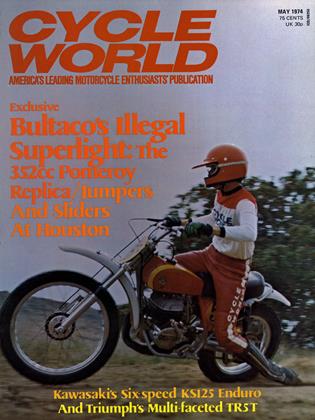

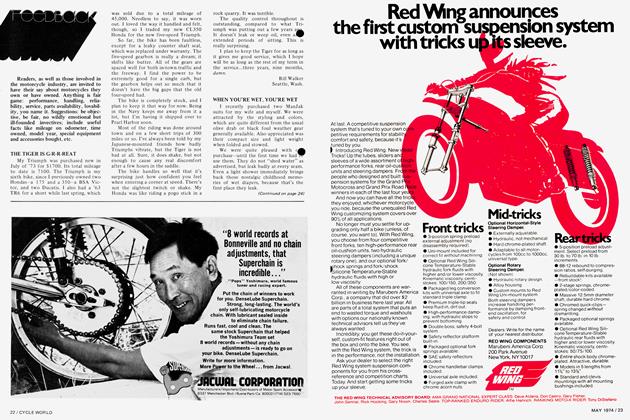

KAWASAKI KS125 ENDURO

American Influence Rears Its Lovely Head.

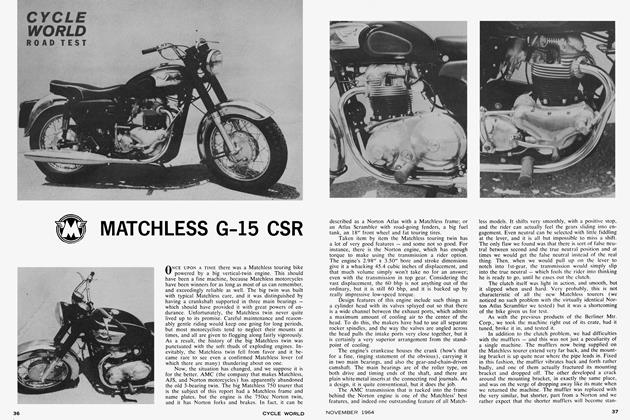

Cycle World Road Test

In these days when the smallbore field is crammed chock-full of machines whose dual purpose tags should more accurately read: neither purpose, it is refreshing to see and ride a motorcycle with the versatility and spunk of the KS 125. The new, green trailbike is a welcome replacement for its marginally successful F-6 predecessor.

Still powered by a rotary valve Single, the power plant has been narrowed to a very acceptable 10.75 in. Part of this was accomplished by the minor relocation ot the carburetor bulge. It now sits slightly higher, which keeps it out of the way of most of the damaging off-road elements. The KS can be successfully squeezed through tight trails that are normally reserved for its pistonport contemporaries. Also, with ground clearance at an abundant 10.3 in., and a sturdy bash plate fitted to the lower frame rails, rock steps and unavoidable logs present little, if any, problem.

The KS sports a single, two-ring piston that rides on needle bearings at the wristpin. The connecting rod uses roller bearings on its lower end. The top ring on the piston is a Keystone ring, which is different than a standard square ring. The upper surface of the ring is machined with a downward slope, declining as it approaches the piston. Under compression, this slope pushes the ring outward and makes for a tighter seal, providing a more efficient compression stroke. Yet on the power stroke, the ring relaxes once the exhaust port opens, thereby reducing drag and the resulting friction.

Power delivery through the wet, multi-plate clutch, mounted-en the primary shaft for start-in-any-gear purposes, is to a slick-operating six-speed gearbox. Although a little stiff when the bike was new, it loosened up immediately; and > missed shifts were simply not to be found.

The transmission operates with a down-for-low pattern and the ratios are spaced perfectly. First gear will pull the steepest gulley shots, while sixth is good for a 65 mph cruising speed on the street. And pavement handling displays none of the wallowing oversteer of the F-7 175 that we tested last month. The KS can be pushed to the limits of its trials universal tires; and the frame behaves.

Not only is the frame good on the street, but this one handles the rough stuff in smart fashion. Plonking around at slow speed, the suspension offers little of the cushy ride of the XL-175. But as you pick up speed, it begins absorbing irregularities, and settles right in to do its job. Even though restricted by what, according to today’s standards, can be called short-travel forks, they graciously take up what most riders will ask them to, with room to spare.

Precise damping eliminates any of the pogoing effect that is found on many small bikes. But pogoing at the rear end is another story. Kawasaki’s dual-purpose shock absorbers have never been anything special. But these worked just like we hoped and prayed they would. It did take us a while to get used to the fact that even though we were on a Kawasaki, we didn’t have to drastically decelerate for the rougher terrain. Occasionally we bottomed them, but only when we were overdoing it.

The hopping in the rear end comes in only when the atrocious rear brake is applied. That brake is a powerful unit that is acceptable on the street—but just barely. It is so insensitive and mushy, that out in the dirt, locking it up will be an undesired, but highly common practice. Even when you finally manage to develop a feel for it, the rear end jumps around so badly under braking that it is totally unacceptable.

We did discover a way to keep the rear end from bouncing, > but it is complicated and requires much practice to be used effectively. If the throttle was rolled on slightly (say, about 14 on), and the bike descended hills in gear, then the resulting torqueing of the rear end of the motorcycle downward forced the wheel to follow the contour of the ground beneath it. But trying to work the throttle, the rear brake and the front brake simultaneously is going to require some serious coordination.

The front brake is neat. As progressively powerful a binder as you’ll ever need on a trailbike, the highly polished conical hub is one of the most attractive we’ve ever seen. Only the Dural hub on the front end of the Bultaco is better looking. Moreover, the Kawasaki’s incorporates a speedometer drive. Many enduro riders will be purchasing KS125 front brakes to use on their bikes, it is light, strong, not too expensive, and has the speedo drive.

For the earnest enduro rider, several minor things will have to be altered or replaced before the KS125 can be considered a serious contender. The rubber-covered footpegs should be cast aside and replaced with toothed items. Naturally, the trials tires should be discarded, and knobbies slipped on in their place. Something ought to be done about that nasty rear brake, as well.

Some of our staffers didn’t like the shape of the handlebars, while others didn’t notice. Most likely, you’ve got a particular style that you’ve come to know and love, and you’ll substitute a pair of those.

Grips are poor; and the break-away levers won’t survive more than one tumble. But these are minor things that are not terribly expensive to alter. The real bummer is the seat. While adequate for a 30 to 40-mi. street jaunt, there’s no way that anyone, except those with the most highly padded posteriors, is going to make a 100-mi. enduro on it. The seat is hard and narrow. While the narrowness doesn’t bother slimmer people, the heavier ones will find their rumps slowly starting to spread on them as they ride, requiring middle-of-the-street and standing-at-the-stoplight readjustments.

The only thing that saves the seat from being just plain rotten is the manner in which it is mounted. With two spring-loaded hooks at the rear, and a slip-fit tongue up front, the seat can be completely removed in a matter of seconds. Under the seat is the foam air filter element housed in an F-7-type canister. The element kept dirt out throughout our test period.

Beneath the air filter is the toolkit. While average by trailbike standards, the plastic container is excellent. Nearly unbreakable and easy to get to, it has a “living” hinge that should last forever.

At 230 lb. test weight, the KS125 is not the lightest trailbikes, but you’d never guess its weight by riding it. ease with which it can be flicked about out on the trail makes it teel much lighter. Everything from high-speed sweepers to trials terrain is within the realm of the machine’s maneuverability, powerband and speed-for-every-need gearbox.

Overall, we are very pleased with the KS125. But there are several things about the bike that particularly excited us, since we’ve been wondering just how the new KX125 (Kawasaki’s yet-to-be-released motocrosser), is going to stack up. If the geometry is similar, the suspension is just as up to the task as the KS’s was, and the power plant as cooperative and willing, it is going to be a helluva bike. But if your interest lies in the dual-purpose market, the Kawasaki KS125 should be near the top of your list. It is on ours. |0]

KAWASAKI

KS125 ENDURO

CIFICATIONS

$699