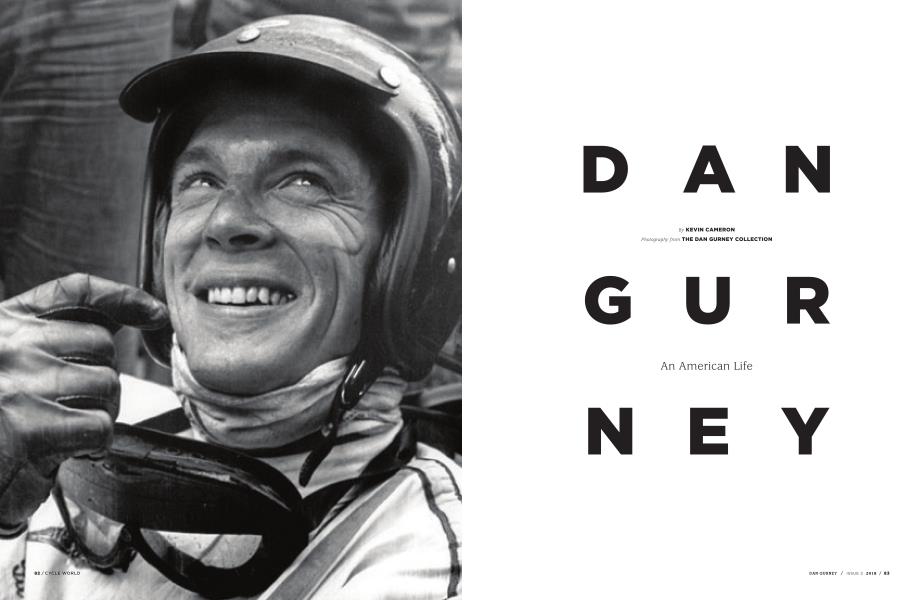

DAN GURNEY

KEVIN CAMERON

An American Life

Dan Gurney—champion racecar driver, vehicle engineer, motorcyclist, and racing-car builder—died this year at age 86. He came to greatness at a time when American industry, innovation, and power were peaking. His father, retiring from New York City’s Metropolitan Opera in 1947, moved the family to Southern California. The gigantic U.S. aircraft industry—much of it located in that state—had just produced 302,000 military aircraft and 810,000 aircraft engines for World War II, and the plants, tooling, and people who accomplished that miracle remained active. Surplus outlets were bursting with rolling bearings, hydraulics, electronics, and more.

A brand-new twin-engine P-38 fighter with full gas tanks was $1,200. Men got rich recovering the platinum electrodes from hundreds of thousands of surplus aircraft spark plugs. Technology in 1947 was almost free. Want trick aluminum or steel alloys? It was everywhere.

Americans had acquired a worldwide reputation as innately innovative and creative, mainly because U.S. industry had incidentally put technology and information within the reach of every interested American youngster. Children grew up in a rich environment, taking apart and putting together clocks, building and flying model airplanes, experimenting with Erector and chemistry sets, and then going on to weld and fabricate hot-rod cars—or creating an industry. For Americans, play could be a highly sophisticated activity.

Teenage Dan Gurney immersed himself in the hot-rod culture: building cars, taking them to the dry lakes, and then branching into other forms of racing. He could drive, but he could also build, and the interaction between the two activities would inform his whole life.

Motorcycle enthusiasts know that Gurney also loved bikes. In recent decades, he could be found at speed on SoCal’s “racer roads,” enjoying the series of ever-improving feet-first bikes his shop engineered and built under the name Alligator.

“I had a Montesa,” Gurney said to me once. “A good bike—it would do 100 mph. But I was never quite comfortable. I’m tall!” Worst was going downhill on dirt: “I always felt as if I were going to tip over forward! I did, a couple of times.”

So in 1976 he built something that did fit him, the ultralow Alligator A1, with a Honda 350 engine up front. Singles were compact, but he came to want more power than would fit into a one-cylinder space. Some beautiful CNC parts went into those singles all the same.

Gurney’s accomplishments are burned into our collective motorsports culture. With Mario Andretti, he was one of just two Americans to win races in the four major racing categories: Formula One, Champ cars, the FIA sports-car championship, and NASCAR.

How? It came naturally, and it came by accident.

Racing and winning expanded as sponsors, seeing his energy, expanded his opportunities. The biggest of all was truly an accident. Goodyear, wanting to break the Firestone race-tire monopoly, came knocking at Indianapolis only to have all their sponsored drivers switch tires. Remember, this wasn’t now, where everything has to be PC and certified perfectly safe. You could promote cars and tires and gasoline based on glamorous success in racing. Goodyear decided it needed its own cars. Who could build them?

In those days, big corporations had no idea about racing, so they had to find and trust those who did. It was a time of sharp culture shock, such as stock-car-builder Smoky Yunick getting a call to get to the airport where a corporate jet waited to whisk him—dirty shop pants and all—to Detroit to tell the boys with big engineering degrees how to win races.

So in 1965, with Carroll Shelby and Goodyear funding, Gurney started the racecar production facility that would soon be named All-American Racers. AAR today occupies 75,000 square feet in Santa Ana, California.

“Dan Gurney’s life tells us that it’s essential to have many interests and the energy to pursue them. ”

While Gurney was racing in just about every series he could find during a driving career running from 1957 to 1970, he was also beginning to build 158 racing cars under the name Eagle. AAR is the only builder in the U.S. to have designed and built a winning FI car, winning Champ cars, and winning FIA sports cars.

When it came time to look for an outfit to build a 3.0-liter V-12 to power Gurney’s FI car, he knew that English airflow specialist Harry Weslake had done a promising high-rpm project for Shell. Implemented as first a 375cc and then a 500cc four-valve-per-cylinder twin, and with a nearly flat combustion chamber thanks to narrow valve angle and steep ports, the 500 gave 76 hp at just over 10,000 rpm. Sound familiar? It was very close in concept to what Keith Duckworth would unleash in 1967 in the Cosworth DFV FI V-8. Six of those 500 twins, built in V-12 form, could add up to over 400 hp! That would become the engine in Gurney’s Eagle FI car, which he drove to victory at the 1967 Belgian GP at Spa, averaging more than 145 mph.

A few days previously he had won the Le Mans 24-hour Sports Car Championship race in France, where instead of swigging the champagne presented to him on the podium, he put a thumb over the mouth of the bottle, gave it a shake, and shot celebratory foam over everyone in reach. It became instant tradition, continuing on podiums to this day.

When Yvon DuHamel’s Team Hansen race tuner Steve Whitelock saw Indy cars with drilled brake discs, he saw them as a fix for Kawasaki’s hefty brakes. He drove over to Gurney’s shop where the staff enthusiastically worked up a pattern of half-inch holes. When people saw Yvon’s “holey rotors” at AMA road races, they became an instant must-have.

Gurney built a big, narrow-angle V-twin to power his latest Alligator motorcycle but was offended by its heavy natural vibration—something that requires balance shafts to quell. He said of it, “My experience is that things vibrate for a while, then fatigue, and fall off or fall apart.”

He knew something better was possible because he’d devoted his life to better and knew how to get to it. In 2015, he revealed AAR’s “moment-canceling engine”—a compact parallel-twin with two geared contra-rotating crankshafts that zero out primary shaking and leave no rocking moment—without balance shafts. “Big” means 110 cubic inches from a 5.14-by-2.65-inch bore and stroke. “Smooth” means being able to reach high revs without shaking itself to pieces. “Power” means 260 hp. With now-common variable cam timing, this engine will pull hard from low revs to peak. When I say “build,”

I mean in-house—because the shop has everything required, including not only the usual machine shop equipment but also specialized apparatus such as a large-scale autoclave for carbon-hber-reinforced-polymer structures. You need one if you plan to make racecar tubs—or advanced airframe parts.

Gurney and his leading staff would show up at Yamaha’s Monterey Aquarium MotoGP celebrations, parking several Alligator versions at the curb outside.

He knew everyone because he had been everywhere, always. His office is rich with memorabilia; when I was there in 1997, I spotted what I thought was a sleevevalve cylinder from the Centaurus engine of a Sea Fury-based air racer. Warplane models covered a long bookcase. History is dense in these buildings—the Hall of Photos and the Eagle Museum’s long line of race cars. At lunch, Gurney and his men had endless topics to discuss; on and on we went, hopping from subject to fascinating subject. These men were interested in mist lubrication of gears and rolling bearings, supplying just enough oil to lubricate and cool, not enough to lose power to churning. It was clear they were reading everything. I felt seriously privileged to be there.

You might think such a busy man, designing and building a series of unique motorcycles while designing, building, and driving race cars, would be the classic, driven Type-A male whose family is an afterthought and whose rising blood pressure puts an end to it all at age 60. No such thing. Type-A’s compete with their children, but Dan passed control of his company to son Justin in 2002, then himself carried on to age 86. The attractive conclusion that for Gurney, life was not a compulsion but a pleasure. A feast.

Dan Gurney’s life tells us that it’s essential to have many interests and the energy to pursue them.

AAR has taken on much besides racing in recent years. California was long a center of U.S. aircraft production, with milelong plants surrounded by concentric rings of subcontractors and job shops. As that has ceased to be the case, organizations such as AAR, which can literally take on any project, have become less common and more valuable. Gurney said, "Justin saved the company”—meaning that by taking on specialized aviation projects, AAR and its people have remained busy.

Dan Gurney’s career has been a long series of successes that have unlocked further opportunity. He saw his moment-canceling engine as another such key— as he put it, “One more chance to make an impression.” As if it were needed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue