YOUR NAME HERE

RACE WATCH

Erv Kanemoto's No Name Race Team

KEVIN CAMERON

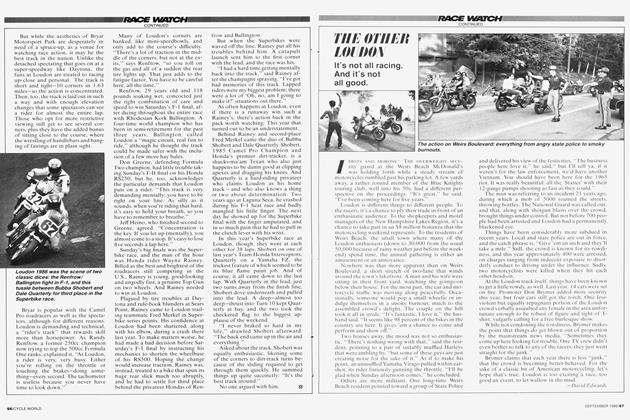

MODERN RACING, AS HARD AS IT IS TO ADMIT, is not driven by passion or competitive spirit or technology. It's driven by money. The ultra-exotic Grand Prix machinery circulating the world's road courses are billboards for sponsors who have provided money-and lots of it.

Team Kanemoto Honda, long successful in 250 and 500cc GP motorcycle racing, is chronically unable to

find a major sponsor. Why? Last year, teamed with Max Biaggi, Erv Kanemoto’s team was funded by Marlboro, an experienced long-time racing sponsor. But two years before that, with 250cc World Champion Luca Cadalora on a 500. the team’s fairings were literally white-no sponsor. This year, despite top times from rider John Kocinski in test after test, the fairings are again devoid of corporate stickers. What gives?

I spoke to Kanemoto about these problems. He could not, for obvious reasons, say much for publication except that he still had no major sponsor.

General matters first: Racing sponsorship was easier to find before the cigarette-advertising bans in various countries. Several tobacco companies supported GP teams, and a working agreement could be reached in a couple of meetings. After the last race of the season, the track hotel became in essence a bargaining facility. “No one was in his own room-everyone was either in a meeting or wandering around the halls trying to find one,” Kanemoto says.

This is no longer the case; the cigarette-makers have other things to think about, and the smaller sponsors that are available offer their money contingent upon a major sponsor being found. Everyone would like a long-term relationship, but in this time of transition to non-cigarette sponsors, they’re hard to find.

Another factor is the uncertain current status of GP racing. Is it really switching from two-stroke to fourstroke? Is this just a PR blitz, or a cover for lack of direction? Some of the proposed future formulas sound more like jumble sales than major racing. Which class will get the public’s attention, GP or World Superbike? Advertisers are unsure.

Racing also has become impractically expensive-partly by accident. In the late 1980s, as GP racing’s popularity was peaking and TV dollars were swelling, riders wanted their share. Because top riders can now demand so much (Doohan’s yearly take reportedly approaches $6 million), teams must sometimes choose between riding talent and equipment; even fairly large teams cannot afford both in full measure.

The other side of this coin is that the bike-makers also cashed in, raising their “per seat” equipment leases to the Sl-million-a-year range. Both of these factors-higher rider contracts and racebike leases-came into being when sponsorship justified it. That’s no longer the case, but the > high costs remain.

Sponsors’ aspirations have changed. The only reality today is TV, which means that even the most casual contact between media and team equipment/personnel must be of broadcast quality, with the sponsor’s logo always nicely centered. This means more than crisp, fresh uniforms and one or two professionally painted tractortrailer transporters. Today it means carrying backdrop flats that must be erected inside the pit building to create a photogenic environment-stagemanaged and professionally lit-in which the normal and traditional duties of race team personnel are then carried out. This, in turn, means either hiring more staff or diverting mechanics and engineers to roadie work.

Sponsors used to fund teams. Now

the trend is to fund riders. Why the change? Once you create an effective TV personality and a product association, you can’t afford to drop it. Marlboro wanted Max Biaggi on a 500

because he is an influential personality on Italian TV. That’s what put Biaggi on Kanemoto’s Honda 500s last year. When Biaggi went to Yamaha this year, Marlboro went with him.

This changes the status of race teams. Once they were the enduring foundation of racing. Today, their status is looking a bit secondary, like that of a

tennis star’s shoe company.

This is as unfortunate for motorcycle manufacturers as it is for Kanemoto and other small team own-

ers. It used to be “Kenny Roberts wins on Yamaha,” creating a strong rider/manufacturer identification. This weakens as riders seek their advantage in corporate style-from the highest bidder, leaving us with a rider/sponsor identification.

Kanemoto isn’t racing for business reasons. If he just wanted a nice little business, he could create one with few of the present headaches. He could prepare customer engines or consult at tests. But he wants to be on the front lines, confronting the raw variables of engines, handling and riders.

This brings us to the particular. The fact that Team Kanemoto is about racing and not about business may unintentionally make communication difficult. Businessmen-which is what potential sponsors are-understand other businessmen. Each is trying to get the most out of his money and they know, accept and act on this. This leads to problems when a businessman talks to someone with other priorities.

Once in the 1960s, my rider and I approached our sponsor for a Ceriani fork, which at the time was $105. “Fine,” he told us, “just sell the fork that’s on the bike, and then we’ll talk about a new fork.” To us, this was ridiculous because a racebike without a fork is useless. To the sponsor, paying twice for a single function was ridiculous. Racers and businessmen are on different wavelengths.

The potential sponsor wants to know how much, and the answer is millions. “I give it to them-bottom line first, then itemized,” Kanemoto says. Honesty requires accuracy, but a businessman may see this more as a negotiating ploy than as a hard figure. Now we’re into game theory, and I hear the reader thinking, “Why doesn’t he just get himself a business manager to handle sponsorship, so he can get on with his own work?” Part of the answer is The Dan Gurney Effect.

The potential sponsor is interested, at least in part, because racing is romantic and its heroes are famous, respected figures. He wants to shake hands with Dan Gurney-not with his hired business manager. The other drawback is that the business manager is really in business for himself-not for the team.

Rider choice is the next issue. Potential sponsors naturally check up on their planned investment through the usual grapevine phone calls: What about this Cadalora? What about this Kocinski fellow? Kanemoto’s position as a private team owner obliges him to seek undervalued riders, men with winning talent who are perceived otherwise for various reasons-or factory teams already would have snapped them up.

These hypothetical phone calls surely had an effect when Kanemoto teamed with Cadalora. He believed Cadalora could ride a 500, but sponsors clearly disagreed. As it turns out, on the right track, on the right day, Cadalora was as brilliant on a 500 as he had been on a 250-but those tracks and days turned out to be in the minority.

Kocinski was World Champion on a Castrol Honda RC45 Superbike in 1997, but was billed second to Carlos Checa on the Spanish MovistarHonda 500cc GP team in 1998, getting lackluster results. Washed up? Hardly. Kocinski has incredible drive and ability, but he is not an appliance that can be plugged into any outlet-he flourishes under the right conditions and not otherwise.

Kanemoto strongly believed that Kocinski would go fast again as soon as he found appropriate circumstances. The pre-season tests have shown Kanemoto to be right. Potential sponsors and the advisors they talk to may not be so sure.

What about last year, when Biaggi on the Kanemoto Honda 500 won the first GP of the year and thereafter challenged Doohan? Although Biaggi now acts as if teams and bikes are interchangeable, we know it was Kanemoto who tailored the unfamiliar Honda 250 to Biaggi in 1997 (he became World Champion on it) and > the 500 to him in 1998. It was Biaggi’s own intemperate behavior, ignoring black flags and starter’s orders, that lost him the championship.

In our slick media world of product and human packaging, a private GP team has become an ad agency that must sell $5 million to $8 million dollars’ worth of space every year. Kanemoto is widely and rightly admired because his success in racing has not come at the sacrifice of his human qualities. It is a cruel irony that the work he loves forces him to attempt something so far from his nature-the role of salesman. What you see is what you get, a man who knows how races are won, not a corporate package.

Gresham’s Law states that a debased currency drives a sound currency out of circulation-as in the disappearance of U.S. silver money when the new copper-nickel coinage was released. As I see it, the debased currency is the irresistible world of TV, in which winning races is becoming secondary to just looking good on the screen. The sound currency is the solid, race-winning work of veteran race engineers like Erv Kanemoto.

We’ll see.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue