THE GREAT UNCONFORMITY

IGNITION

WANDERING EYE

CUSTOMS BRING TECTONIC SHIFTS TO MOTORCYCLING

PAUL D’ORLEANS

We had guests for dinner, Suzie Heartbreak and I, and brother Scott spun tales of his rafting expeditions in the Grand Canyon’s geologic depths. The canyon’s many-hued strata are a time line of compressed ages, but Scott threw a wrench in my reckoning. “Near Lava rapids you pass the Great Unconformity.”

I wait-waited the conversation; how apt a label for a century of custom-motorcycle building.

Change requires unconformity, and that’s where custom builders work, wobbling between established genres and new ideas. They’re outside the mainstream yet impact an entire industry, at times steering the boat from the rear.

In the early days, burning questions of the “ideal” machine bred a lot of talk, sketches, and customized bikes. Harold “Oily” Karslake might have been patient zero, building his “Dreadnought” in 1903, which pioneered a low-mounted, sprung saddle, a powerful engine, and no bicycle pedals—the first pedal-less safety-frame motorcycle. Oily later engineered George Brough’s Superiors, plus of course a custom Brough, the “Karbro Express” with a i,500cc engine, monstrous in the day. Karslake’s combination of a bigger motor and catchy name is evergreen, and his ideas shaped the industry.

Great waves of customization followed. The Cut-Down of the late 1920s was the first uniquely American style: HarleyDavidson “J” twins with shortened and lowered frames. Add a tuned engine, and the Cut-Down became the hottest bike around, lighter, lower, and better handling than stock. H-D offered its first “racing” twin-cam engine for the road in ’28, the JDH, and JDH Cut-Downs were the fastest American bikes prewar. Faster than the EL Knucklehead introduced in ’36, which embarrassed H-D brass, who promptly had them outlawed from AMA competition. JDH riders wore “outlaw” as a badge of pride...the start of all that.

Cut-Downs were American café racers long before the term and pushed the industry to tighten up their lines. The name “café racer” was coined in 1950s England, where riders converted road bikes into racer look-alikes. By the ’60s, factories were building their own versions, even slapping trendy checker tape on production bikes. The Italians were far ahead though, seemingly forever building hot rods, but definitively stole the Brits’ stamp on the café trend by making the fastest motorcycles in the world in the ’70s; first the Ducati 750SS, then the Laverda Jota. It was the apex of the café trend, and customizers invented the style.

Harley-Davidson resisted nonconformists for decades; it took young Willie G. to incorporate custom cool. First he built a café racer (the XLCR) then addressed the chopper craze with the Low Rider, transforming custom stance into a new genre—the cruiser. H-D even subtly embraced the outlaw thing with an advertising shift, hinting that anyone could buy a little V-twin badass.

Nowadays, smart factories cultivate custom builders as an externalized R&D. BMW, H-D, and Yamaha dole new bikes to small shops around the globe, gaining press attention and reflected grooviness. BMW successfully flipped its dependable-appliance image by working with top-tier stylists like Roland Sands and hiring a Swedish chopper dude (Ola Stenegard) as head bike designer. Thus the Great Unconformity wobbles toward the mainstream...but never quite settles.

BY THE NUMBERS

1930

THE RADICAL DREADNOUGHT IS BUILT-THE FIRST CUSTOM? HARLEY-DAVIDSON ARCHIVES

1977 HARLEY INTRODUCES THE XL CAFÉ RACER

2013 ROLAND SANDS UPDATES THE BMW R90S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Ten Rest

September 2015 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

September 2015 -

Ignition

IgnitionCw Product Spotlight Arai Corsair-X

September 2015 By Matthew Miles -

Ignition

IgnitionCw 25 Years Ago September 1990

September 2015 By Blake Conner -

Ignition

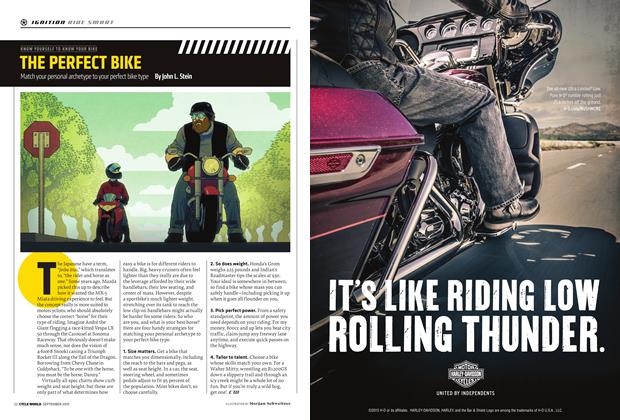

IgnitionKnow Yourself To Know Your Bike the Perfect Bike

September 2015 By John L. Stein -

Ignition

IgnitionFuelishly Complicated

September 2015 By Kevin Cameron