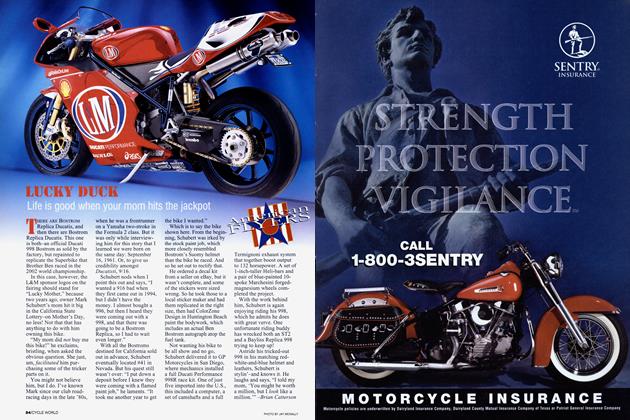

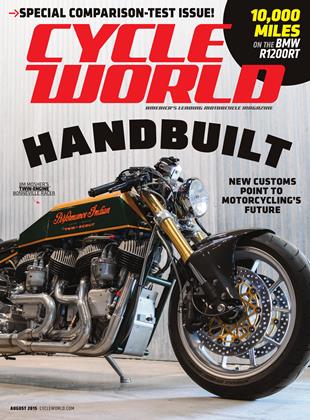

the HANDBUILT SHOW

FEATURES

PREVIEWING ALT.CUSTOM 2.0

Paul D’Orleans

THE ALT.CUSTOM WORLD IS HAVING AN EXISTENTIAL CRISIS.

“What’s next?” is topic A in my conversations with builders from the US and Europe, as it’s clear people are a little bored. Anyone who’s insta-clicked away from a same-same no-fender CB custom with plank seat/swapped tank/ Firestones understands my point. A daily blog feed is a hungry beast, and while the original Alt.Custom style is a successful formula even in print (witness 50,000 copies of The Ride), it’s also a victim of that popularity; our eyeballs are saturated. What comes next in this ever-expanding globalized scene is a multiple-choice question, and Austin’s Handbuilt Show had some intriguing answers. While Handbuilt is more about craft than prognostication, the show is broadminded enough to include everything from old-school choppers, vintage bikes, CB customs, bob-jobs, café racers, and Bonneville record-breakers, plus a few machines that bump against the edge of the new, pointing the way forward to Alt.Custom 2.0.

The Handbuilt Show’s guiding principle is self-explanatory: A generation of screen-gazers needs a kick in the pants and a wrench in the hand. Because cussing at the old motorcycle you’re building, or any real-life hobby, is a path to build confidence, wisdom, and character—a nod to the “soul craft” thing. When applied to motorcycle customization, it implies innovation, technical exploration, and the development of skill. Most machines at the show in Austin fit within established patterns (chopper, café, bob, tracker) in that never-ending recycle of established styles—variations on a theme. Keeping one’s work within classic parameters is sensible given the dangers of constantly “evolving” a style, which can lead to baroque horrors, like just about any chopper built in the ’90s. Still, the custom world has an important dialogue with the motorcycle industry as a whole, being a source of innovation and exploration of “what if” tech, new styles, and even the relationship between rider and machine.

For example, Handbuilt Show host Revival Cycles is working out interesting ideas with its latest machines, and the Pyro, Hardley, and especially the J63 are good examples of next-wave customs. They hark back to classic café and tracker styles, with an unmistakable 2015 twist. The J63, already featured in Cycle World (March issue) is a “silver machine” built around a two-valve Ducati 900SS engine, with a house-made stainless-steel trellis frame and beautifully complex swingarm, an orthodontist’s wet dream. The fork assembly should give industry designers pause, as Stefan Hertel created a superior method of fixing fork tubes into their yokes via collets rather than the cheaper slot/clamp, resulting in a stiffer front end. Best of all, the J63 has tight café racer lines, promising lightness and speed, and it delivers. It suggests what 2.0 is all about: genuine innovation, good design, and the possibility of an excellent ride. I’ve had the thrill of spanking this ultra-light beast through knotted canyon roads, and I can happily report it’s a hell of a lot of fun. If this is the way forward with Alt.Customs—performance mixed with art—we’re all in.

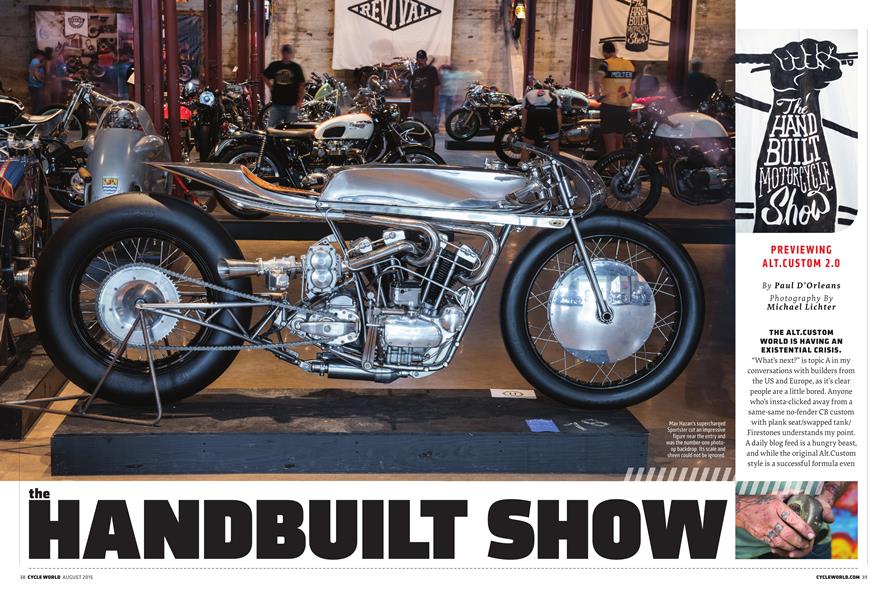

Max Hazan brought his supercharged Sportster, another silver machine ablaze with innovation, though Hazan keeps one foot planted in fine-art turf. With its exposed roller bearings on outrigger plates, huge automotive tires, and enormous scale, his Sporty might not be suitable for real-world road use, but it’s totally functional, and other builders are no doubt taking notes. Especially with neat touches like a fairing that pivots slightly with the forks (while not attached to them) and a girder fork, which looks like a telescopic unit. Hazan is cool with customers mounting his work on a wall, as he’s more interested in what’s mechanically possible within the definition of “motorcycle,” with his particular bent toward architected frames. Plenty of big-name customizers have built reputations on art bikes (which used to be called show bikes), and not many rocks were hurled at Arlen Ness for installing supercharged Sportsters into “difficult” chassis in the early ’70s. We were all too busy saying wow, and Hazan seems destined for great things.

In the history of custom motorcycles, one factor has typically trumped all others on the choice of the host machine: They’re cheap. Early choppers were usually salvaged ex-police Harleys, Tritons were originally spare Manx frames with wrecked Bonneville motors, and CB customs are built from the tens of thousands of survivor Hondas in garages worldwide. Today, ’90s Ducati twins are perfect custom fodder, combining exciting performance with low resale value, and the Handbuilt had plenty. On the, “Why hasn’t anyone done that before?” tip, Ian Halcott’s “Una” mimicked the trellis-tube chassis of his Ducati with a set of trellis girder forks, painted red like the frame, making a veritable bridge from axle to axle. With a hydraulic shock controlling movement, a girder fork offers a limited range of motion but zero dive under braking and less deflection in corners than tele forks. The big factories—especially BMW—are exploring the theme, though Halcott’s Due had too-rad-for-factory styling, with twin aluminum fairings on the girders.

Tim Harney applied some lovely aluminum bodywork to a Ducati 748, with a proboscis aluminum fairing and abbreviated seat. Apogee’s “Sasha” was a slick reboot of a Monster S4RS, which curiously also featured dual fork fairings (leggings?) much like Halcott’s, albeit over standard telescopies—a new trend? Apogee’s Ducati was clean enough for a double take and looked like a factory piece with its professional blue/black/white paint job, proving that even radically modified machines gain a kind of credibility when painted in the manner of a factory. It’s a trick Walt Siegl uses to good effect on his limited-production customs, and he too displayed a Ducati-based machine at the Handbuilt, a slick café racer in muted gray.

Ducatis aren’t the only cheap/fast option for builders; Buells have hit a low point on the market, and we’re seeing more of them tweaked and experimented with. Steve Jones of Jonz Customs brought an XB12 with a solid-blade girder front end and his own trellis frame wrapped around the Harley-based lump. As the all-black paint and black motor had a stealth effect in the “mood” lighting at the Handbuilt, it seemed a lot of folks missed this radical bike, which is a shame; it’s a bold machine. While it’s no more outrageous to riff on Erik Buell’s work than that of an Italian chassis designer, Buell’s contribution to the H-D story was all about performance and handling. Tossing aside his work to experiment with an even more radical frame and front end is kind of exciting, like it might lead to a schoolyard brawl: “Oh, yeah?” “Yeah!” I’m definitely curious how it handles, as the look is pure streetfighter.

In the vein of beautifully crafted innovation, Jeremy Cupp of LC Fabrications caught everyone’s eye with his speedway custom “#7,” which mated a Buell Blast crankcase to a Ducati cylinder head. His hand-built rigid frame was very much a scaled-up speedway racer and featured a gutted upsidedown fork with external springs and hydraulics connected by a link, a crafty method of reducing unsprung weight. Cupp’s work was clever and clean, with a few tricks reminding me of Ian Barry’s Falcons, like a spring-and-ratchet tuckaway kickstart lever. It was the bike everyone talked about, so it was no surprise it won People’s Choice Award.

This was the second Handbuilt Show, and organizer Revival Cycles corralled 110 bikes into a huge converted warehouse with an outdoor yard, where the American Motor Drome was planted. Not many bike shows have a “wall of death,” but they should:

It feels wickedly dangerous when a 1928 Indian rocks the wooden boards beneath your feet, while trick rider Charlie Ransom sits sidesaddle, snatching paper money from outstretched hands. Entry to the Handbuilt is free, as is the Motor Drome; anybody could walk through the wide-open doors, and a broad swath of humanity filled the huge roomstudents, hipsters, locals, builders, and bikers. With generous space between machines, it was even possible to study fabrication details on the Friday and Saturday party nights, when the joint was hopping. The Handbuilt Show sits on the April MotoGP weekend at Circuit of The Americas, the track about 30 minutes distant, and is literally well situated to facilitate the conversation between unfettered custom innovators and the best design engineers in the industry. Our sport’s future is right here.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOn A Wing

August 2015 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

August 2015 -

Ignition

IgnitionRacer Ride

August 2015 By Blake Conner -

Ignition

IgnitionSomething For Nothing?

August 2015 By Kevin Cameron -

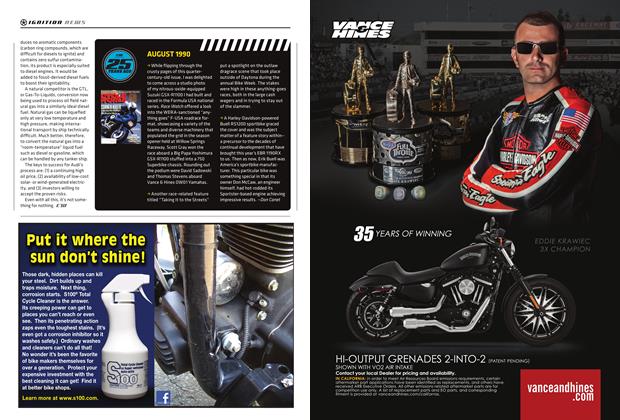

Cw 25 Years Ago August 1990

August 2015 By Don Canet -

Ignition

IgnitionTop Priority: Street Riding Use Your Imagination

August 2015 By Nick Ienatsch