4TH AGE OF MOTORCYCLING

IGNITION

WANDERING EYE

FROM FUNCTION TO FASHION, AND BEYOND

PAUL D’ORLEANS

As the 20th century stumbled over World War II, a new kind of motorcycle took root in the US, and we're still grappling with the implications. In the mid-1940s, pioneering artist-bikers modified their Harleys, Indians, and Brit-bikes not for performance but for style. While bob-jobs had hit the streets by the mid’30s, mimicking Class C racers, by the decade’s end a few riders added wacky pinstriped paint jobs, flashy chrome, upswept exhausts, and high handlebars to their bob-jobs. There isn’t a name for these machines. They’re beyond bob-jobs—basically proto-choppers—and are the earliest form of the motorcycle as Art Object. Converting bikes into flamboyant statements of personality defined the cutting edge of cool in 1947, just as it does today.

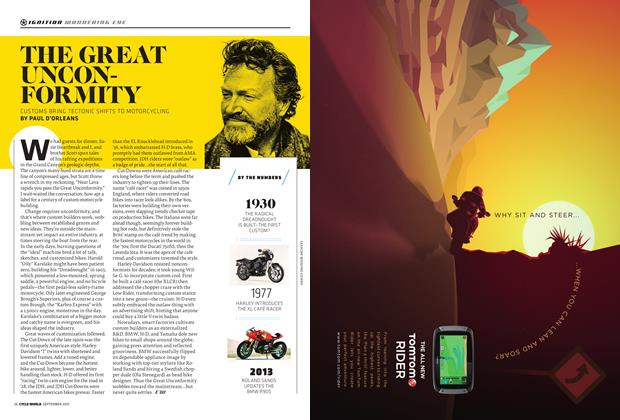

Thus began the Fourth Age of Motorcycling, when performance took a back seat to aesthetics. The early birthto-toddler days of the mid-i8oos to early 1900s was the age of Experiment, with new ideas hammered out in a thousand small workshops. The next age was Utility (post-1910), when motorcycles became reliable transport, not mere oddities. In developed economies, the age of utility was superseded as early as 1930 by the age of Pleasure, when inexpensive cars allowed bikes to be used as desired, not required. The unexpected flowering of the show bike in the 1940s proved a motorcycle could be admired solely for its beauty, with sculptural qualities outweighing questions of function.

The first hot-rod show, organized by Wally Parks in January 1948, included some far-out bikes: heavily chromed, painted up, stripped down. From that show forward, twoand four-wheeled customs immediately laid rubber, and both the Oakland Roadster Show and

Bonneville Speed Trials were on the calendar within months; motorcycling would never be the same. Show bikes grew increasingly unridden/unrideable in the 1950s, and the outlandish stretch of the chopper by the early ’60s was undeniably about fashion over function. Before Easy Rider, one couldn’t buy readymade chopper parts. “It was all about making stuff and no money,” says Mike Vils, who worked for Ed Roth in ’68. But that changed quickly with the global chopper craze of the ’70s, which became a folk art industry.

In a 1998 Time column, art critic Robert Hughess called the custom bike “one of the distinctive forms of American folk art.” But as late as 2011, Frederick Seidel asked in the New York Times, “Is the era of the motorcycle over?” The definitive “no” came from a groundswell of custom builders, with hyper-hip photographers and clothiers tagging along. Clever factories have hitched their stars to young builders, while going places an in-house design team simply can’t.

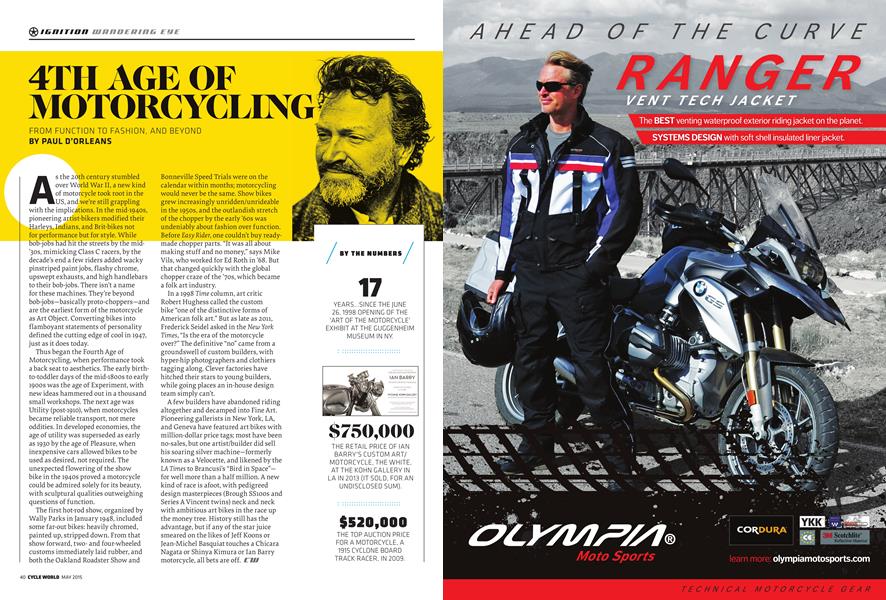

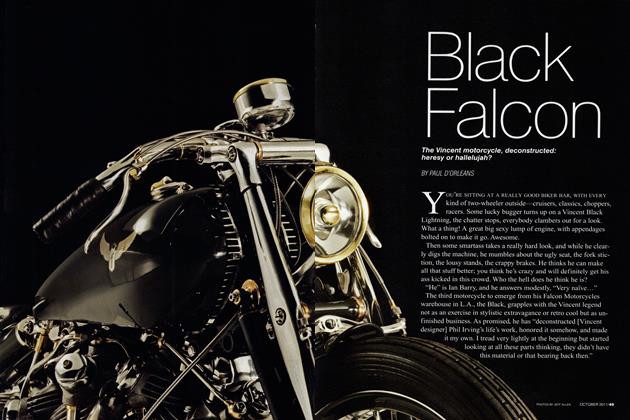

A few builders have abandoned riding altogether and decamped into Fine Art. Pioneering gallerists in New York, LA, and Geneva have featured art bikes with million-dollar price tags; most have been no-sales, but one artist/builder did sell his soaring silver machine—formerly known as a Velocette, and likened by the LA Times to Brancusi’s “Bird in Space”— for well more than a half million. A new kind of race is afoot, with pedigreed design masterpieces (Brough SSioos and Series A Vincent twins) neck and neck with ambitious art bikes in the race up the money tree. History still has the advantage, but if any of the star juice smeared on the likes of Jeff Koons or Jean-Michel Basquiat touches a Chicara Nagata or Shinya Kimura or Ian Barry motorcycle, all bets are off. ETMM

BY THE NUMBERS

17 YEARS...SINCE THE JUNE 26, 1998 OPENING OF THE `ART OF THE MOTORCYCLE' EXHIBIT AT THE GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM IN NY.

$750,000 THE RETAIL PRICE OF IAN BARRY'S CUSTOM ART! MOTORCYCLE, THE WHITE, AT THE IOHN GALLERY IN LA IN 2013 (IT SOLD, FOR AN UNDISCLOSED SUM).

$520,000 THE TOP AUCTION PRICE FORAMOTORCYCLE,A 1915 CYCLONE BOARD TRACI RACER, IN 2009.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Third Dimension

May 2015 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

May 2015 -

Ignition

IgnitionTo Infinity And Beyond

May 2015 By Blake Conner -

Ignition

IgnitionKenji Ekuan, 1929-2015

May 2015 By Kevin Cameron -

Ignition

IgnitionCw 25 Years Ago

May 2015 By Blake Conner -

Ignition

IgnitionOn the Record Abe Askenazi

May 2015 By Brian Catterson