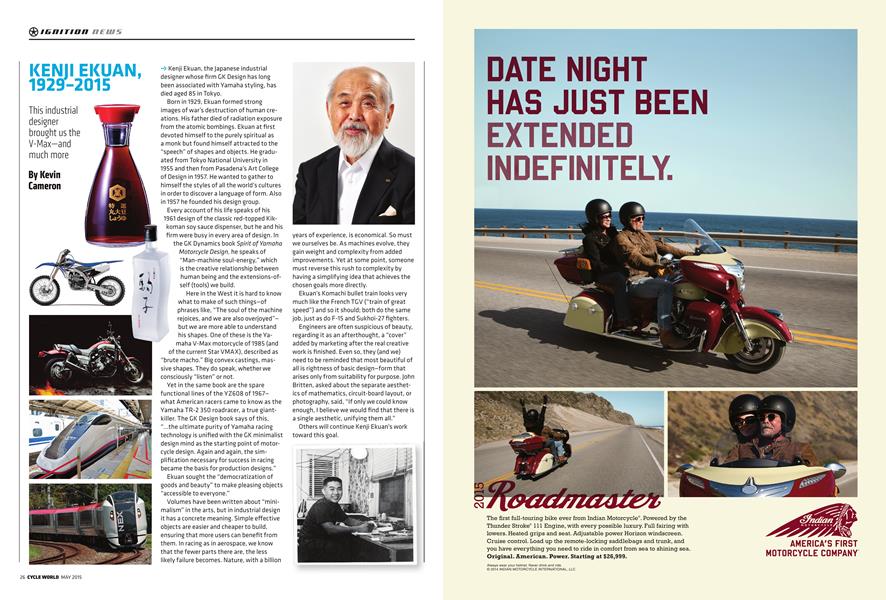

KENJI EKUAN, 1929-2015

IGNITION

NEWS

This industrial designer brought us the V-Max—and much more

Kevin Cameron

Kenji Ekuan, the Japanese industrial designer whose firm GK Design has long been associated with Yamaha styling, has died aged 85 in Tokyo.

Born in 1929, Ekuan formed strong images of war’s destruction of human creations. His father died of radiation exposure from the atomic bombings. Ekuan at first devoted himself to the purely spiritual as a monk but found himself attracted to the “speech" of shapes and objects. He graduated from Tokyo National University in 1955 and then from Pasadena’s Art College of Design in 1957. He wanted to gatherto himself the styles of all the world’s cultures in orderto discovera language of form. Also in 1957 he founded his design group.

Every account of his life speaks of his 1961 design of the classic red-topped Kikkoman soy sauce dispenser, but he and his firm were busy in every area of design. In the Dynamics book Spirit of Yamaha Motorcycle Design, he speaks of “Man-machine soul-energy,” which is the creative relationship between human being and the extensions-ofself (tools) we build.

Here in the West it is hard to know what to make of such things-of phrases like, “The soul of the machine rejoices, and we are also overjoyed”but we are more able to understand his shapes. One of these is the Yamaha V-Max motorcycle of 1985 (and of the current Star VMAX), described as “brute macho.” Big convex castings, massive shapes. They do speak, whether we consciously “listen” or not.

Yet in the same book are the spare functional lines of the YZ608 of 1967what American racers came to know as the Yamaha TR-2 350 roadracer, a true giantkiller. The Design book says of this, “...the ultimate purity of Yamaha racing technology is unified with the minimalist design mind as the starting point of motorcycle design. Again and again, the simplification necessaryforsuccess in racing became the basis for production designs.” Ekuan sought the “democratization of goods and beauty” to make pleasing objects “accessible to everyone.”

Volumes have been written about “minimalism” in the arts, but in industrial design it has a concrete meaning. Simple effective objects are easier and cheaperto build, ensuring that more users can benefit from them. In racing as in aerospace, we know that the fewer parts there are, the less likely failure becomes. Nature, with a billion

years of experience, is economical. So must we ourselves be. As machines evolve, they gain weight and complexity from added improvements. Yet at some point, someone must reverse this rush to complexity by having a simplifying idea that achieves the chosen goals more directly.

Ekuan’s Komachi bullet train looks very much like the French TGV (“train of great speed”) and so it should; both do the same job, just as do F-15 and Sukhoi-27 fighters.

Engineers are often suspicious of beauty, regarding it as an afterthought, a “cover” added by marketing afterthe real creative work is finished. Even so, they (and we) need to be reminded that most beautiful of all is rightness of basic design-form that arises only from suitability for purpose. John Britten, asked about the separate aesthetics of mathematics, circuit-board layout, or photography, said, “If only we could know enough, I believe we would find that there is a single aesthetic, unifying them all.”

Others will continue Kenji Ekuan’s work toward this goal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Third Dimension

May 2015 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

May 2015 -

Ignition

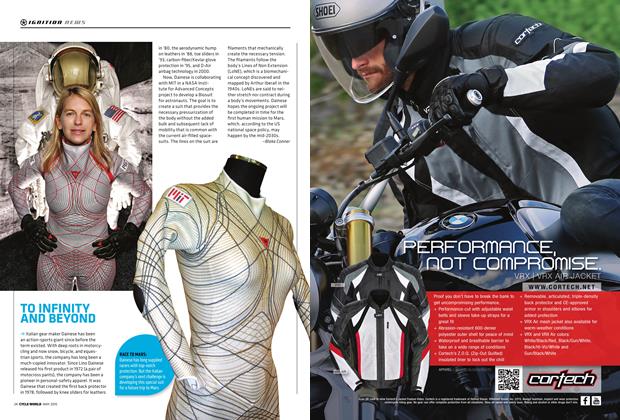

IgnitionTo Infinity And Beyond

May 2015 By Blake Conner -

Ignition

IgnitionCw 25 Years Ago

May 2015 By Blake Conner -

Ignition

IgnitionOn the Record Abe Askenazi

May 2015 By Brian Catterson -

Ignition

IgnitionKnow Your Bike Back Off, Jack

May 2015 By John L. Stein