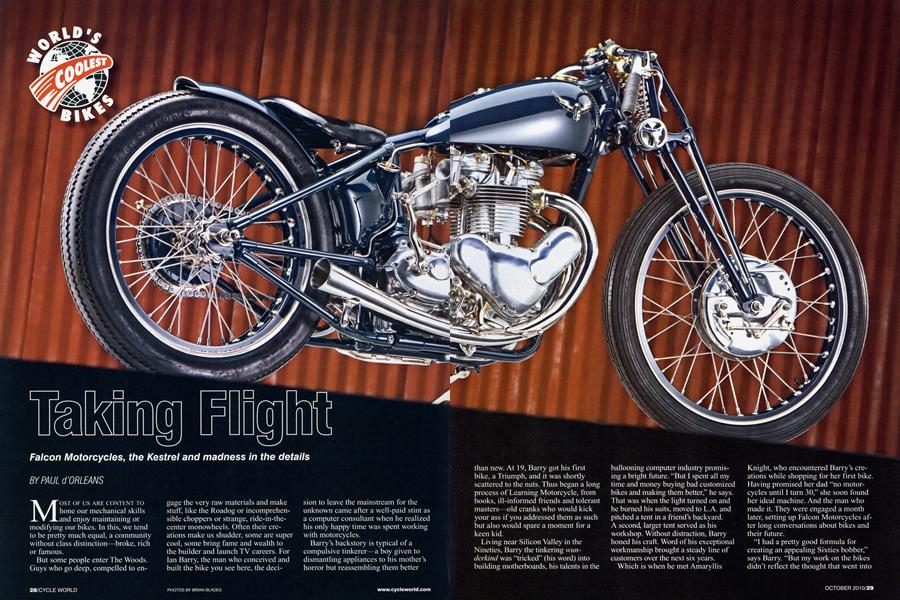

Taking Flight

Falcon Motorcycles, the Kestrel and madness in the details

PAUL d’ORLEANS

MOST OF US ARE CONTENT TO hone our mechanical skills and enjoy maintaining or modifying our bikes. In this, we tend to be pretty much equal, a community without class distinction—broke, rich or famous. But some people enter The Woods. Guys who go deep, compelled to en-

gage the very raw materials and make stuff, like the Roadog or incomprehensible choppers or strange, ride-in-thecenter monowheels. Often their creations make us shudder, some are super cool, some bring fame and wealth to the builder and launch TV careers. For Ian Barry, the man who conceived and built the bike you see here, the deci-

sion to leave the mainstream for the unknown came after a well-paid stint as a computer consultant when he realized his only happy time was spent working with motorcycles.

Barry’s backstory is typical of a compulsive tinkerer—a boy given to dismantling appliances to his mother’s horror but reassembling them better than new. At 19, Barry got his first bike, a Triumph, and it was shortly scattered to the nuts. Thus began a long process of Learning Motorcycle, from books, ill-informed friends and tolerant masters—old cranks who would kick your ass if you addressed them as such but also would spare a moment for a keen kid.

Living near Silicon Valley in the Nineties, Barry the tinkering Wunderkind was “tricked” (his word) into building motherboards, his talents in the

ballooning computer industry promising a bright future. “But 1 spent all my time and money buying bad customized bikes and making them better,” he says. That was when the light turned on and he burned his suits, moved to L.A. and pitched a tent in a friend’s backyard. A second, larger tent served as his workshop. Without distraction, Barry honed his craft. Word of his exceptional workmanship brought a steady line of customers over the next six years.

Which is when he met Amaryllis

Knight, who encountered Barry’s creations while shopping for her first bike. Having promised her dad “no motorcycles until I turn 30,” she soon found her ideal machine. And the man who made it. They were engaged a month later, setting up Falcon Motorcycles after long conversations about bikes and their future.

“I had a pretty good formula for creating an appealing Sixties bobber,” says Barry. “But my work on the bikes didn’t reflect the thought that went into a single [Triumph] casting lug or timing cover. What if I built a whole bike like that? What would that be?” He established his fundamental ethos: “I would not make any compromises anywhere. Every piece of hardware, every curve, every part of my bike should reflect the thought that went into that timing cover.”

Falcon #1, the “Bullet” (built for actor Jason Lee), put that rigorous ethos to the test in 2008, and the bike gained broad acclaim, magazine covers, infinite web chatter and a “Best Custom” win at the Legend of the Motorcycle Concours. Of course, the overabundance of attention fueled eye-rolling naysayers: just one Falcon, so much fuss. Can #2 live up to the hype?

Over the next year, Barry kept his nose to the grindstone with that second machine, the Kestrel, which started as a blown-up basket-case ’70 Bonneville, which had eaten a tranny bearing and “expanded” the gearbox. The busted cases allowed Barry the freedom to make heavy modifications, because he felt “the unit [construction] engine... I just had a problem with it; it always looked stunted.” When Triumph combined the previously separate engine and gearbox in 1963 into a single case, “something got lost, and I wanted to take it back. It’s got the potential to be a really neat design, but it falls short.” The audacity of “taking it back” meant hacking off the gearbox and reconfiguring the entire motive drive assembly. Had anyone ever made a later Triumph engine into a so-called pre-unit?!

Leaked photos of the near-finished Kestrel revealed a beautiful though hardly flashy motorcycle. The assembled machine is so tightly conceived that it appears almost ordinary at first— not a custom at all, more like a production machine. But from a parallel vintage reality. As if George Brough and Edward Turner somehow both had a child named Ian, who insolently robs their factory parts bins to make stuff like the Kestrel’s Frankenprimary, which mates two generations of Triumph covers. The post-’63 primary case has a nice swoosh, the earlier a subtle dome. With a cutaway artfully separating them, exposing the chain and dry clutch, the

drive side is terribly sexy, yet it looks like a design Turner might have made. Had he actually been cool.

What ultimately proves intoxicating about the Kestrel is the tension between its succinct normalcy, its sweet wholeness, against the evidence of a mindbending volume of time spent on the details. Every part has been thought about, redesigned and fabricated or rebuilt by Falcon, and it shows. And there are the simply luxurious details, which mark Barry as a man of tremendous artistic talent, as well as one clever bastard. Items like the gearbox adjuster are complicated not in a Phil Irving Vincent way, but carved into graceful, organic shapes. Thus, while bracing the gearbox against axial play and positively locking chain tension, that little bracket could grace the neck of Tilda Swinton.

Same with the gearshift linkages— three pieces of metal transferring upand-down foot movements to the gear-

box—straightforward in principle, devastatingly elegant in execution. Then you notice the shift lever pivots inside the footrest, and something inside you goes, “Oh, $#&%!”

The Falcon-built rigid frame has three struts triangulating the rear axle, a feature last seen in 1930 on Brooklands racers. While intended to keep the rear wheel rigidly fixed, the center stay fills a void while drawing a horizontal speed line. A pair of three-spoke alloy adjuster knobs beside the girder fork are in-house versions of 1920s André steering dampers, lifted from the headstock of a racing Douglas. The Falcon-built fork has a third strut, echoing the rear frame, with Webb-style girders inspired by those used on Velocette KTT racers. Looking over the Kestrel, it’s clear the Falconer’s eye peered straight past the Sixties— the usual custom hangout—deep into vintage territory for inspiration, reaching right into Twenties racing photographs and grabbing what he wanted.

That frame, fork, tanks, covers, every nut and bolt, and a thousand ancillary parts were made in-house at Falcon. The team of three talented fabricators who work with Barry left TV-famous workshops to join him, and they never want to work anywhere else, even though finishing the Kestrel in time for its debut at the Quail Motorcycle Gathering this past spring meant far too many 16-hour workdays.

After Falcon’s investment of some 2000 man-hours, the bike generously rewards sustained inspection. The frame top tubes separate pannier gas tanks, held together by a trio of discreetly functional turnbuckles to perfectly adjust the gap between them. The Amal TT carbs have tiny wing-like lockable throttle stops. The leather saddle conforms to the junction of frame to rear fender, kicking up to follow the curve of the wheel, yet it is sprung underneath for its full length, which nobody had done. The clutch and brake levers look like old outside pivot items, but actually pivot inside the handlebars. Again, nobody. Routing the internal throttle cable through that brake lever pivot required yet more ingenuity. The cable is completely invisible, exactly the sort of detail overlooked on casual inspection, or even a third look, but time spent with Kestrel brings these kinds of continual surprises.

No excuses necessary for functionality, either; the Kestrel runs as good as it looks. The frame geometry took months of research to nail down. “I didn’t want to be too extreme,” says Barry. “Stick with what works and make subtle changes. I wanted 5 inches of ground clearance but a very low eg, keeping all weighty fluids down low. The head angle is 29 degrees—one more than stock. I wanted stability at speed, with fluidity in the corners.”

I rode the Kestrel, and it’s clear Barry got the formula right, as the bike feels tiny and agile yet totally solid around bends and over bumps. No waggle, no weave, no headshake, it feels exactly like a pedigreed vintage racer. Plus, it’s very quick with its 750cc engine and 340-pound weight, and the engine runs through the rev range oh-so-smoothly. Shifting is seamless, and braking about

as good as it gets with a twin-leadingshoe Triumph backing plate. The sound from that two-into-one open megaphone is a deep and menacing growl.

The Kestrel has a rare purity and depth in both aesthetic and functional execution. It is a machine artfully informed by history and exquisitely crafted in modern times, using a mixture of time-honored, by-hand work and modern CNC machining. The question remains whether such art is financially sustainable (Falcon plans to produce runs of custom parts for vintage bikes), but the prospect of seeing the next eight of Falcon’s proposed “Concept 10” series at future events is damned exciting. The next machine, based on a Vincent Twin, is expected to be finished in late summer, and Barry looks forward to exploring “the pure romance of the Black Shadow. I want to simplify it to bring out the beauty, cost be damned... I want to deconstruct someone’s life’s work, try to honor it somehow, and make it my life’s work.” If anyone has a chance of doing it, Ian Barry appears to be the man. n

Paul d ’Orleans is a serial vintage bike owner, student of motorcycling and tireless blogger ihttp.V/thevintagent. blogspot.com) on all things old bike. He consults for Bonhams Auctions and is knee-deep in writing a book.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Price of Sanity

OCTOBER 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupExclusive Bmw K1600gt And Gtl

OCTOBER 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Muscle Revealed

OCTOBER 2010 By Andy Downes -

Roundup

RoundupOverhauled!

OCTOBER 2010 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

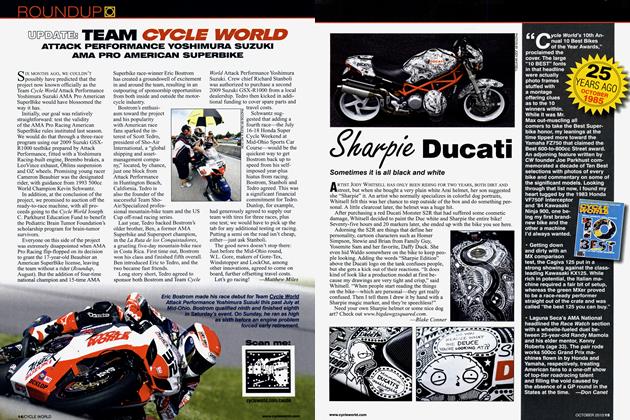

RoundupTeam Cycle World

OCTOBER 2010 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

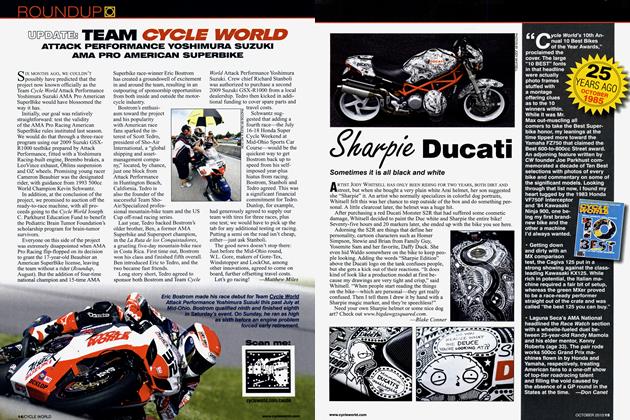

RoundupSharpie Ducati

OCTOBER 2010 By Blake Conner