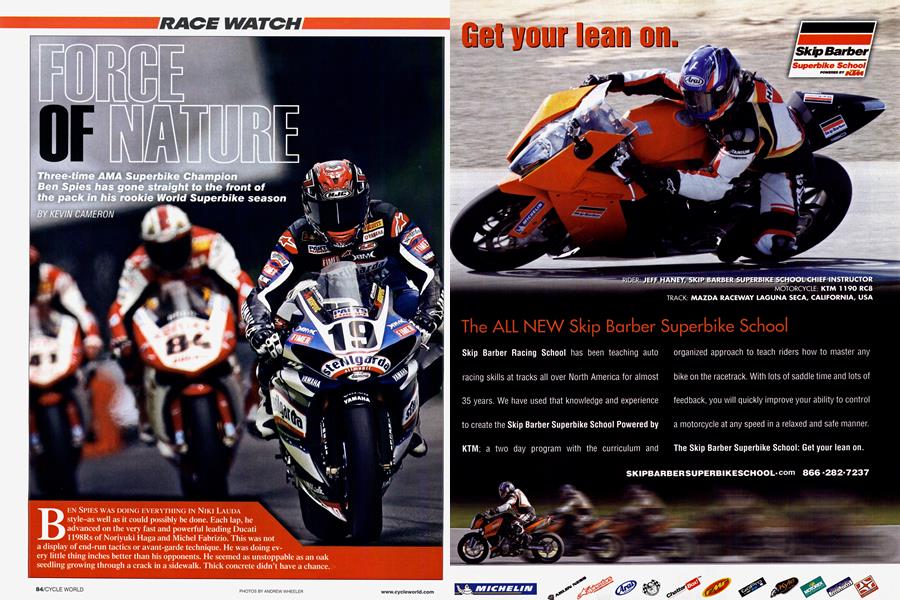

FORCE OF NATURE

RACE WATCH

Three-time AMA Superbike Champion Ben Spies has gone straight to the front of the pack in his rookie World Superbike season

KEVIN CAMERON

BEN SPIES WAS DOING EVERYTHING IN NIKI LAUDA style—as well as it could possibly be done. Each lap, he advanced on the very fast and powerful leading Ducati 1198Rs of Noriyuki Haga and Michel Fabrizio. This was not a display of end-run tactics or avant-garde technique. He was doing every little thing inches better than his opponents. He seemed as unstoppable as an oak seedling growing through a crack in a sidewalk. Thick concrete didn't have a chance.

In race one at Autódromo Nazionale Monza this past May, Spies’Yamaha engine quit on the last lap while he was leading and within sight of the checkers. Fabrizio, madly whirling his helmeted head in celebration, took the win. It didn’t matter. Spies came back just as focused in race two and did it again, just as inexorably, inches at a time. Fabrizio fought back around, but Spies found parts of his tire that were still alive and used them to win. He was also careful to implement sensible fueleconomy measures-such as slowing down in the final laps.

Think of Spies’ recent race history: Before coming to World Superbike this season to ride the new 90-degree-crankshaft Yamaha YZF-R1, he had to invent ways to beat “Mladin the Terrible,” his teammate at Yoshimura Suzuki in AMA racing. Mat Mladin can be as dire and strong as fate itself, but Spies endured the white noise of the Australian’s 360-degree assault to win three Superbike titles. Mladin leaves little to chance; he is a lifelong thinking rider and a hard trainer, driven by an almost-tragic need to win. Spies worked with whatever Mladin left on the table-not much. No wonder Spies appeared unstoppable in Italy.

It was clear to me that the Yamaha changes direction quickly, and that it is notably more stable during braking than the Ducatis and the Ten Kate Honda CBR1000RR of Ryuichi Kiyonari, third in both races. Asked about this, Spies said, “The Yamaha is really good on the front end, and I can be really aggressive braking.”

Back in 2002, the first season for the 990cc four-strokes, braking instability put many a MotoGP test rider on the ground. With weight 98 percent on the

front tire, rear-tire grip was easily broken by flawed engine-braking control, allowing weave instability to suddenly “diverge’-increase to essentially infinite amplitude. A rolling tire grips and has direction; a sliding tire doesn’t care which way it goes. But isn’t this just a matter of getting the right slipper-clutch adjustment? Think about it: Clutch back-torque release pressure is always the same, but the gear ratios change as the rider shifts up and down. Slipper clutches help a lot, but they are just a compromise.

While braking, the Ducatis swing lazily from side-to-side in flamboyant arcs, apparently in control, but just as certainly requiring that their riders manage the extra motion. Spies could stay focused, his Yamaha stable. Kiyonari’s Honda gave a fast, scary shiver during braking-a wet dog shaking-seemingly telling its rider, “Do that too often and I’ll hurt you!”

At Monza, the Ducatis had clearly stronger acceleration and maybe a bit more top speed, but Spies could lap faster. How can that work? I spoke with his crew chief, Tom Houseworth, in Yamaha’s paddock hospitality area. (Race paddocks today are clusters of exclusive sidewalk cafés, full of people, eating, drinking and networking. The nuts and bolts of racing go on in the garages and behind the long row of transport trailers.)

“Ben wants more power,” said Houseworth. “Ben wants a lot of things. I tell him to ride the bike. Riders think Yamaha is here to help them win, but Yamaha was here before they were born. Yamaha is here to win races. The reason Ben is riding the bike instead of someone like me is that he can make a difference.”

An example? “Ben has to get on the throttle way early,” said Houseworth. “It’s the only way.”

Asked about this, Spies said he gets back on the gas 10 meters earlier than his competition. “I’m just very smooth with the throttle,” he remarked.

I thought of Freddie Spencer in 1982 and '83. He was winning Grand Prix races on a three-cylinder Honda that started life at 108 horsepower, in a field of Fours making 135-150 hp. How did that work? Higher corner speed was the basic answer-and getting on the throttle and starting to accelerate earlier. That’s what riders lacking acceleration or top speed have had to do since the beginning. And that’s what Spies is doing.

Top speeds at Monza were interesting, no one being surprised that Max Biaggi’s new Aprilia RSV4 was fastest in the Superpole sessions at 202 mph. Yukio Kagayama’s Suzuki recorded 201 mph, but Spies’Yamaha managed “only” 195 mph. Sound familiar? That was Valentino Rossi’s position in his first year on a Yamaha in 2004-to be always several “clicks” down from the opposition. What Rossi’s engineer, Jeremy Burgess, said then applies now: “Which would you rather have? Ten meters extra at the end of the one straight? Or that same 10 meters gained off every corner?”

Every time Spies arrives at the turn-in point of a corner, his bike is stable and he wastes no time waiting for it to settle, either from braking instability or from arriving “hot.” That lets him get immediately to the business of turning the bike on the chosen line, then getting it under throttle. Two hundred miles per hour gets our attention-big numbers do that. Winning races is more complicated.

If Spies can get on the throttle “way early,” why can’t the others, seeing what he does, do the same? The answer is that all top riders always have the throttle open as far as the impartial physics of traction and their worked-out riding styles permit. The Honda NSR500 of the late 1980s was clearly superior to the Yamaha YZR500 in power, but if NSR riders tried to throttle up with the YZRs, they slid or fell. But when the Honda got its first change of firing order in 1990, its riders could for the first time match the Yamaha men. Does the R1 ’s new 90-degree crank contribute to this? Spies and Houseworth each thought about this for a perceptible moment, then said they thought not.

Will more of everything arrive soon from Japan? “It takes a long time to get things from Japan,” said Houseworth. “Those people are very conservative.”

This, to paraphrase the old song, “Puts the load right on Ben,” and he is carrying it, learning circuits he has never seen before quickly enough to set pole after pole-and win races.

“The Ducatis are really strong in acceleration, and that made me pick up the throttle really early,” said Spies. “Yamaha has new stuff coming along-to help off the corners.”

We know that top riders gather, categorize and retrieve information very rapidly, which is essential to circuit learning. This is the essence of intelligence. More than one person watching Spies’ long-time mentor Kevin Schwantz on a new circuit has done a double-take. Their first impression is, “Why is he so erratic? He never takes the same line twice!” After watching a little longer, this changes to admiration. “No! He’s taking those many different lines because he’s running a new experiment in every corner, every lap of practice! How does he keep it all straight in his mind?”

I asked Spies about his circuit-learning technique. “I just try to dissect the lap into different parts and work on them,” he responded. Whatever the method, his results are impressive.

I asked about racing on series-spec Pirellis, having heard that after 20 laps they can feel “like rain tires on a drying track.”

“They fall off a little bit (in the later laps of races),” said Spies. “Pirelli could make them better, but they don’t have to. The important thing is that they're the same for everybody. And they’re getting better.”

In the second race at Monza, onlookers noted Spies carefully adjusting lean angle during some corner exits. Was he using a chosen region of the tire? The conservation of tires is more than simply limiting spinning and sliding. It has to do with not giving any particular part of the tire more work than it can handle.

For American fans, Spies is a goto-the-front, take-charge rider in the grand tradition of Roberts, Spencer, Lawson, Rainey and Schwantz. Following their examples, Spies doesn’t just ride harder, he rides better. He makes World Superbike-already the best competition at the international level-irresistibly fascinating.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

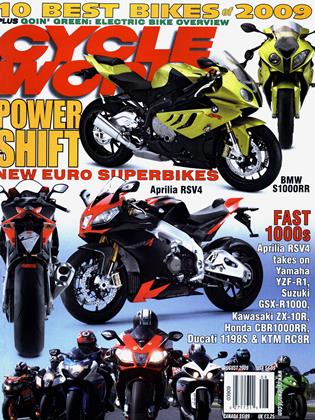

Up Front

Up FrontTen Rest, 2009

August 2009 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Guy of the Moment

August 2009 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCInstruments of Control

August 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

August 2009 -

Roundup

RoundupElectric Arrival

August 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago August 1984

August 2009 By Paul Dean