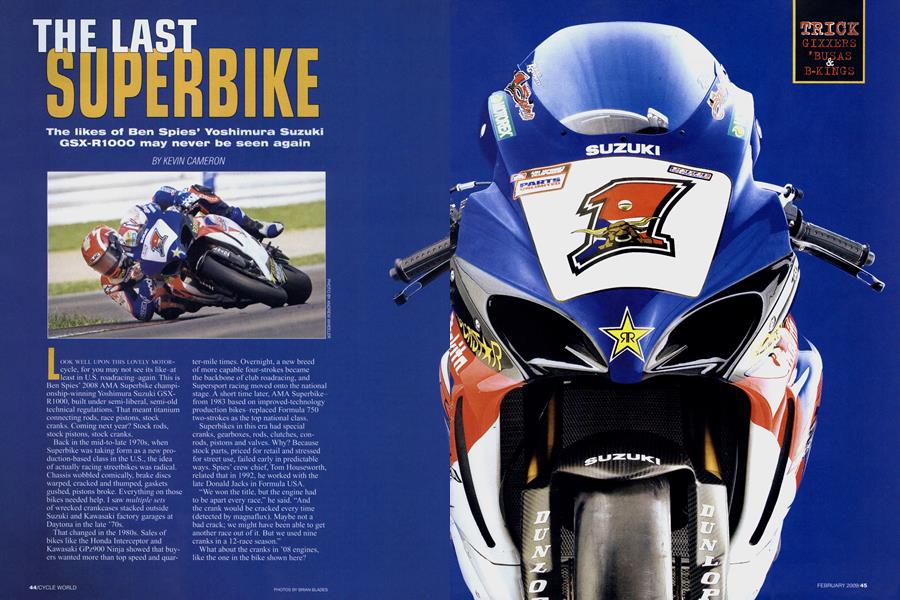

THE LAST SUPERBIKE

The likes of Ben Spies' Yoshimura Suzuki GSX-R1000 may never be seen again

KEVIN CAMERON

LOOK WELL UPON THIS LOVELY MOTORcycle, for you may not see its like—at least in U.S. roadracing-again. This is Ben Spies' 2008 AMA Superbike championship-winning Yoshimura Suzuki GSXRIOOO. built under semi-liberal, semi-old technical regulations. That meant titanium connecting rods, race pistons, stock cranks. Coming next year? Stock rods, stock pistons, stock cranks.

Back in the mid-to-late 1970s, when Superbike was taking form as a new production-based class in the U.S., the idea of actually racing streetbikes was radical. Chassis wobbled comically, brake discs warped, cracked and thumped, gaskets gushed, pistons broke. Everything on those bikes needed help. I saw multiple sets of wrecked crankcases stacked outside Suzuki and Kawasaki factory garages at Daytona in the late '70s.

That changed in the 1980s. Sales of bikes like the Honda Interceptor and Kawasaki GPz900 Ninja showed that buyers wanted more than top speed and quar-

ter-mile times. Overnight, a new breed of more capable four-strokes became the backbone of club roadracing, and Supersport racing moved onto the national stage. A short time later, AMA Superbikefrom 1983 based on improved-technology production bikes-replaced Formula 750 two-strokes as the top national class.

Superbikes in this era had special cranks, gearboxes, rods, clutches, conrods, pistons and valves. Why? Because stock parts, priced for retail and stressed for street use, failed early in predictable ways. Spies' crew chief. Tom Houseworth, related that in 1992, he worked with the late Donald Jacks in Formula USA.

“We won the title, but the engine had to be apart every race,” he said. “And the crank would be cracked every time (detected by magnaflux). Maybe not a bad crack; we might have been able to get another race out of it. But we used nine cranks in a 12-race season.”

What about the cranks in '08 engines, like the one in the bike shown here?

“At the rpm we’re turning, those things just want to jump out of the cases,” Houseworth said. “These days, privateers have access to black-box programming that lets them raise the rev limit. They think the problem is with the valve springs, but I’ve got news for them...*’

For Spies and Houseworth, all this has become irrelevant, as they are off to World Superbike with Yamaha for '09.

The reason for the existence of ultra-clean vacuum-arc -remelted materials-as used in proper race cranks-is that mass-produced materials contain silica inclusions large enough to quickly nucleate cracks under racing stress.

The special needs of competition brought into existence an industry making the race-quality suspension, wheels, brakes and internal parts you’ll find on Spies’ bike. Under the proposed '09 rules, stock forks with modified internals and stock 17-inch wheels will be required. Each aftermarket item w ill have to undergo a homologation process, which costs money (part of much-talked-about “revenue streams”). Factories don't care as long as they get their Öhlins, Brembos or other gear: they’ll add staffers to handle the approval paperwork. I plowed through such homologation in 1971 for the chassis, fuel tank, fork and other parts for my Kawasaki Bighorn 350 roadracer-multiple-v iew photos, proof of insurance. Great fun.

The 2009 rules calling for stock cranks, con-rods, pistons, rings and stock-weight valves have caused serious concern that some of these parts-notably rods-will fail in races. That has happened in British Superbike: engines hav e “come unstarted" in a big way from rod failure. Such a failure really tears an engine up. as the kinetic energy of 12.000-odd rpm is consumed in destroying parts.

Racing Yamaha TZ750s in the early 1980s required us to have three gearboxes for each engine: one in the engine, one in spares and one at the magnaflux facility being inspected. We would infinitely have preferred one good gearbox per engine, as even stock OEM parts weren't cheap. We would have loved aftermarket rods in 1973, when our Kawasaki H2R engines were sawing themselves nearly in half

regularly. Was it the rods or was it the pistons? We never knevv. Both were always so smashed and twisted that you could only guess which broke first.

Houseworth talked about torqueing connecting-rod cap bolts-very critical items. The reliable procedure is to machine the ends of the bolts flat so the stretch of the bolt can be measured directly as it is torqued. Bolts are very stiff springs, preloaded by correct tightening to clamp the parts together. Houseworth noted that if you stretch them too little, they come loose. If you stretch them too much, the metal yields and, again, they fail by being too loose.

Direct strain measurement is illegal now, Houseworth commented, because it is a modification to the con-rod. Where does that leave them? Snug the bolts to 11 footpounds, then swing the wrench 70 degrees. If ev erything's right, if the surfaces are smooth, if the parts weren't made at the end of the production tool’s life, it may be okay.

Head modification is still legal under ’09 AMA rules, but Houseworth indicated that everything depends on the piston, which must remain stock. Both airflow and combustion improvements depend upon coordinated head and piston shaping.

There are praisew orthy reasons for mandating use of stock parts. If you believe that there are really great riders back in the pack-their skill invisible-who would challenge Mladin & Co. if only they rode bikes as good as theirs, you might very well support mandatory stock parts as a way to set their talent free.

Or do rules-makers hope that closer-to-stock bikes will make competitive those factories now choosing to exert less than full team efforts? As Yoshimura’s Don Sakakura noted

with regard to Spies and Mladin, “I don’t see anybody who’s at their level.”

How would a factory team cope with stock parts? First comes 100 percent crack-inspection. Second, since factories pay under dealer net for parts, they change parts for less and as often as necessary. More than one maker has changed

valve springs daily and engines even more frequently. Third big teams just slip in new engines: they don't scrape gaskets

and struggle with cam phase in dusty paddocks. Their pro engine builders keep the supply of dyno-tested fresh engines flowing. Fourth, factories know that a key to finishing races

is accurate statistics on parts TBFs (Time Before Failure),

which they already have from normal development testing. The privateer must either guess or “run ’er ’til she blows” to

get this information.

I asked Housevvorth about wheels. “We have a time limit,” he said, speaking of the magnesium race wheels they have

used. “Two seasons-20 races a season. On my crew, I have one guy who does nothing but wheels.” Will the mandated stock wheels be reliable under racing stress? Will teams have to Zyglo-inspect them for cracks? If so, how frequently ?

Will undiscovered talent come to the front under the new rules? Factory talent scouts already scope the field and audition promising riders on second-level teams. Will “parity” really help privateers more than it helps factories? Idealism is an admirable human impulse. We wait and see. U

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontTrekker's Delight

February 2009 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsArt And the Motorcycle Museum

February 2009 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCInvisible Speed

February 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Giro Heroes

Giro HeroesHotshots

February 2009 -

Departments

DepartmentsNew Ideas

February 2009 -

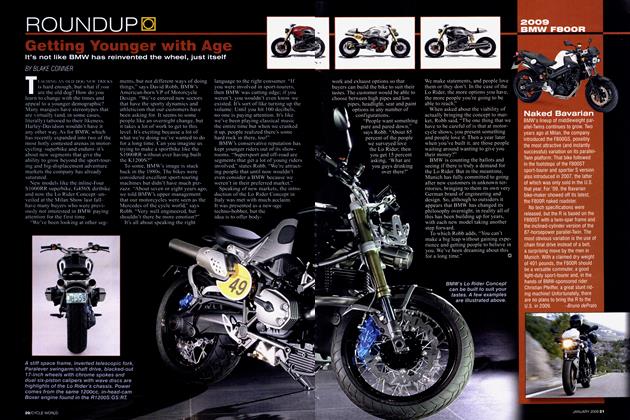

Roundup

RoundupGetting Younger With Age

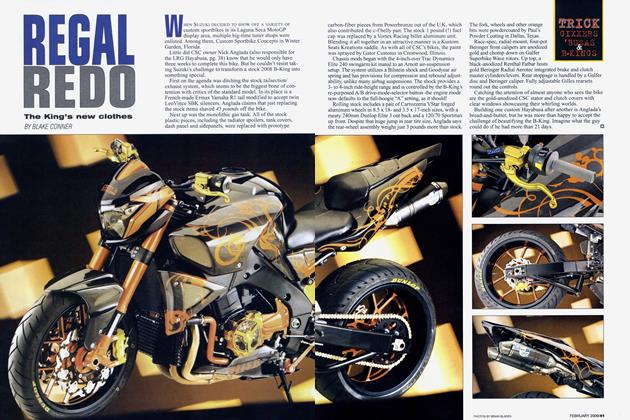

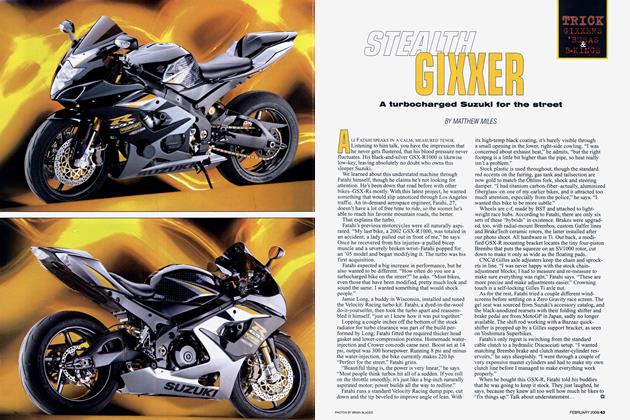

February 2009 By Blake Conner