Pierre's Sex Machines

UP FRONT

David Edwards

SO, DESIGNER PIERRE TERBLANCHE AND Ducati have parted ways, bringing to end an amazing-if not always pacific-chapter in the company’s history. It may be a minority opinion, but I think Ducati will miss Pierre way more than he will miss Ducati.

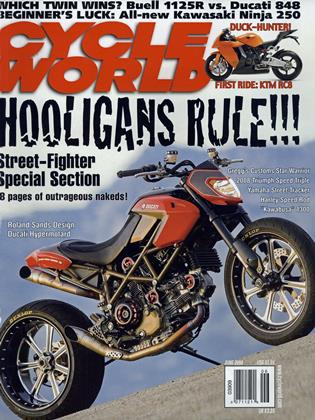

Shortly after collaborating with Roland Sands on this issue’s Hypermotard coverbike, Terblanche announced his resignation. There was not a lot of fanfare. “I’d like to do some new things. I’ll have a studio of my own, and while I’ll still do bikes, I’d also like to work on some other things, maybe boats,” he told England’s Motor Cycle News, hinting that the corporate yoke had begun to chafe a bit too much. “At heart I am really a designer, not a manager, and this will give me the chance to do new things.”

In the few months since, Terblanche has gone subterranean. Our e-mails, texts and phone calls have gone unanswered. Good for him.

Despite the Gallic-sounding name, Terblanche was bom in South Africa in 1956. Twenty-nine years later, he graduated with a master’s degree in transport design from the Royal College of Art in London. After three years in Germany at the Volkswagen Advance Design Studio, in 1989 he unpacked his drafting pens at Cagiva Research Group, working under the celebrated Massimo Tamburini, formerly of Bimota fame and soon to be even better known for his seminal Ducati 916 series (Cagiva, you’ll remember, owned Ducati at the time).

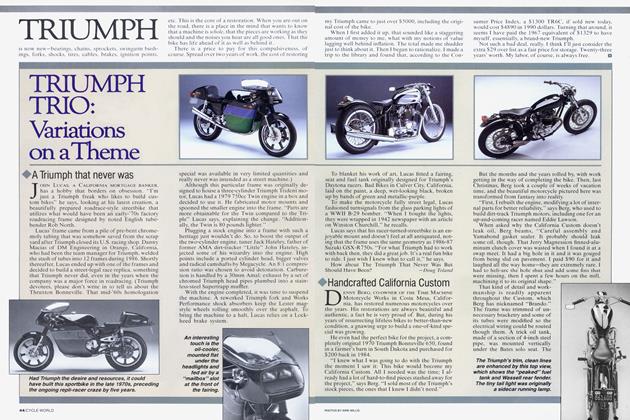

We first saw Terblanche’s unique eye for line and form in 1993 when the Supermono was unveiled. Light and lithe-in fact and in looks-the 550cc racing Single bowled us over.

"A vision in scarlet paint and carbon fiber," wrote Tech Editor Kevin Cameron. "Ducati's new Supermono is a beautiful creation, full of individual character, el egant in concept, a pleasure to behold."

Design professionals thought so, too. We took the bike to Pasadena's famed Art Center Col lege of Design, where Chairman of Transpor tation Design Ron Hill gushed, "This is a corn bination of mechanical realities and a form that is aerodynamic and also aesthetic. It's absolutely gorgeous...a strong statement that doesn’t have a lot of visual entertainment tricks.”

We put the Supermono on the front of our September ’93 issue with a risqué cover blurb borrowed from the 1964 Natalie Wood bedroom romp, Sex and the Single Girl. As part of the story, we took the Ducati to Willow Springs Raceway, then-Feature Editor John Burns in charge of the outing.

“ft weighs 277 pounds without gas,” he noted. “While loading other bikes requires a helper, one person can roll the little Ducati up the ramp and into the back of the CW van with ease. At the track, the same person can roll it back down, lever it onto its stand and pour in the purple Daeco 108-octane while bystanders cross their arms and mutter.

“Bystanders, if they’re in shape, are a necessity with the Supermono. With no starter and a compression ratio in the 12:1 neighborhood, it goes through bumpstart pushers the way the Pony Express went through horses. Down one from neutral is second gear, roll the bike backward against compression, flip the switch on, pull in the clutch and everybody push. Several 10-foot-long black marks later, the engine fires. Keep blipping or it will die. There is no idle circuit mapped into the fuel-injection system,

and the pushers, veterans now, will not be eager again.”

Worth the effort, though. With Don Canet in the saddle, the Supermono obliterated the track’s existing Singles-class lap record by 4 seconds!

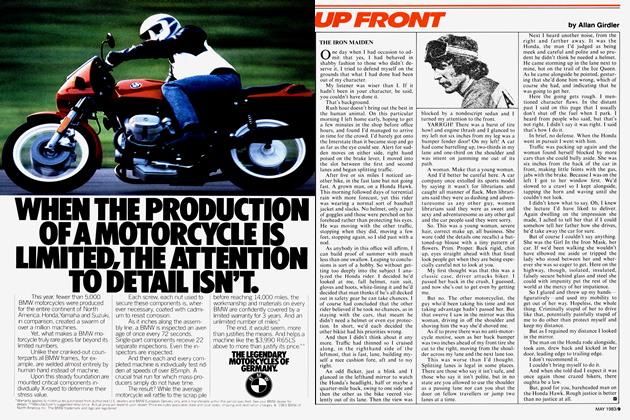

The universal acclaim heaped upon the Supermono did not follow a decade later when Terblanche, now Ducati’s director of design, was given the unenviable task of penning a replacement for Tamburini’s aging masterpiece, the 998. The resultant 999 had detractors almost from the moment the first press photos were shown.

“Designing a bike like the 999 is like standing naked center court at Wimbledon,” Terblanche told us at the time. “What do I say to the critics? Piss off until you’ve seen one in person?”

In retrospect, it couldn’t have hurt.

Hell, judging by all the negative reaction, you’d think the man had put a moustache on the Mona Lisa. I thought it was grossly unfair criticism back then. Still do.

“Nay-sayers, armchair industrial-design critics, unwavering disciples of The Great 916, Tamburini-is-God partisans, all due respect, but now is the time to shut yer yaps,” I wrote in the lead to CWs January, 2003, road test of the bike. “Ducati’s new 999, up close and in the metal, is a stunning piece, spectacular, sublime even. All of a sudden, most other sportbikes look as if they were drawn with a blunt Crayola.”

Later in the test, I was even more demonstrative: “For whatever reason, the camera is not kind to the 999. Its beauty does not readily translate to film. I’ll admit, upon first viewing of the early-release CD images, I was the guy who said, “Well, it’s no 916...

“Of course, how many more years did you want to look at the 916/996/998 family, first sketched by Tamburini in the late 1980s? At some point, a break had to be made, Ducati had to move on. Icons have sell-by dates, too. Besides, here’s the thing: In three dimensions, in natural light, this is a seriously stunning motorcycle. Every atom bears the stamp of the designer. Terblanche has stepped up and delivered. It is a masterwork. Forget the photos-more importantly, forget the 916-the 999 is here to stay.”

Okay, four years ain’t exactly an eternity. The 999 may be gone before its time, but for better or worse we haven’t seen the last Pierre Terblanche-designed motorcycle. I’m betting on better. □