Living with Vincent

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

As I MANNED OUR CYCLE WORLD BOOTH at the Chicago bike show last week, a gentleman walked up and smiled at me with a mixture of forbearance and disappointment.

It was a smile someone named Big Eddie might use just before inquiring about your overdue loan from the mob. I’d seen the man before somewhere...

“You never wrote that column!” he said to me.

“Column?” I asked, as if I’d never heard the word before.

“I stopped at this booth last year and asked why you’d never explained to the readers why you sold your Vincent Black Shadow. I wanted to know what the ownership experience was like.”

“Sure, I remember now,” I said. “Well, I sold the bike mainly to pay off our house loan. But I must admit that I also had a few problems with the bike during the two years I owned it.”

“That’s what you told me last year. I was just wondering why you, as a motorcycle reporter, didn’t tell us what those problems were.”

Where to start? Touchy business.

Vintage motorcycles, you see, are like a religion, and each marque is a different sect. If people are in the OK-Supreme Owners Club and you criticize an OK-Supreme 250, they take it very personally. They may have one of these very bikes parked in the living room, surrounded by candles and incense burners, with a framed photo of Mr. Supreme himself on the wall. They don’t like it if you misunderstand the bike or fail to appreciate its finer points.

Nevertheless, I will step into those deep, cold waters and describe my Vincent experience.

First of all, before I bought the bike I got quite different opinions from ownersand previous owners-who were friends of mine. Half of them said, “Best bike ever built; if you maintain it, a Vincent will run forever,” and the other half said, “Don’t buy one under any circumstances. It’s all smoke and mirrors-complex, expensive and not worth the money.”

And when I bought my 1951 Series C Black Shadow, the mechanic who’d assembled the bike grinned and said, “Welcome to the Masochists’ Club.”

“Heh, heh,” I said uneasily.

So. What was life like in the Masochists’ Club? Well, I’ll begin with the problems from two years’ ownership:

Shortly after I got the bike, the magneto failed. The previous owner, who, luckily, was a great guy, found a really good one and sent it to me. No more magneto problems.

The generator bit the dust, so I got an Alton alternator kit from France. It arrived smashed in the box, so they sent me another one. The teeth barely meshed with the Vincent’s drive gear, but it worked, in shaky fashion.

The clutch, a Ducati 900SS unit that had replaced the original, dragged badly when the bike was hot, so you couldn’t get it in or out of gear while rolling up to stop signs-or leaving them. You had to kill the engine, push it to the side and start over. This was due to a steel pushrod that expanded at a different rate than the aluminum cases and could have been fixed, I later learned, with a different alloy.

The magneto-advance mechanism would occasionally slip on its tapered hub, so the bike would sputter and die. I learned to retime the ignition on the roadside by sticking a piece of straw down a sparkplug hole to measure the distance before top dead center.

The front sparkplug would usually foul out at least once on a day’s ride. I always carried spare plugs.

The bike was hard to start. I’m generally fairly good at figuring out what an engine wants, but the Vincent sometimes defeated me. It had its old, original Amals,

which many people update and replace, and the carb ticklers didn’t flood externally, so you had to time it right. Sometimes it started on the rear cylinder, but not the front. When this bike didn’t start, you needed a trainer in your corner with a bucket and a sponge.

That’s about it for trouble-although it was quite enough. I completed very few rides without doing some roadside work on the bike.

Good stuff?

Well, the Shadow had superb brakes for a bike of this era-or any era-despite what’s been written to the contrary, including in Cycle World's infamous 1965 road test of a Black Fightning. Ride was fluid, compliant and comfortable, and I thought the handling was fine, too, at brisk, non-racing speeds. I’ve heard these bikes can shake their heads and throw you off, but mine never did anything untoward. Also, the

riding position-bars, pegs, seat-was so perfect for me (much adjustment possible) I still think of it as the ideal. The bike is exactly the right size for an adult human, too; not too large or small.

Fovely sound going down the road. Easy, smooth, relaxed lope at 80 mph, almost unknown in bikes of this age. You wanted it to go on forever. But it didn’t always.

Beautiful materials and craftsmanship.

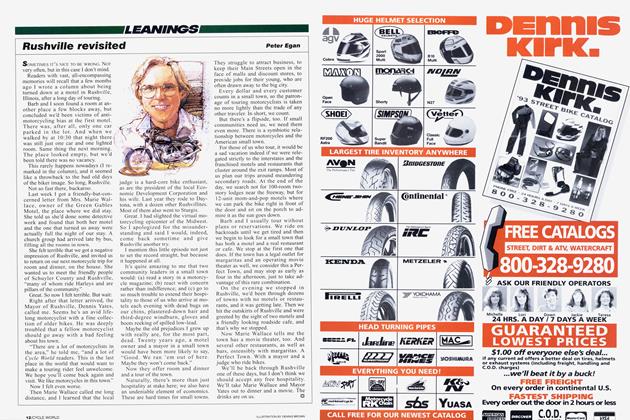

More garage presence than a Jules Verne creation. If Captain Nemo owned a motorcycle, this would be it.

Huge speedometer to remind you that Rollie Free went over 150 mph at Bonneville in 1948.

In the end, I came to think of the Vincent as a magnificent bike that probably needed a few more years of development on the small stuff. Most owners do that development themselves, but I got worn out on the path to perfection and sold the bike.

Would I buy another one?

Not at today’s prices. My old bike traded hands last year for more than twice what I paid for it. I sold everything I owned to get that first Vincent, but now I’d have to sell everything Donald Trump owns, and that’s illegal.

But if I won the lottery, I confess I’d seriously consider buying another one, now that our house is paid off.

I mean, just look at the thing...

Maybe I could get a loan from the mob. I’ll talk to Big Eddie. □