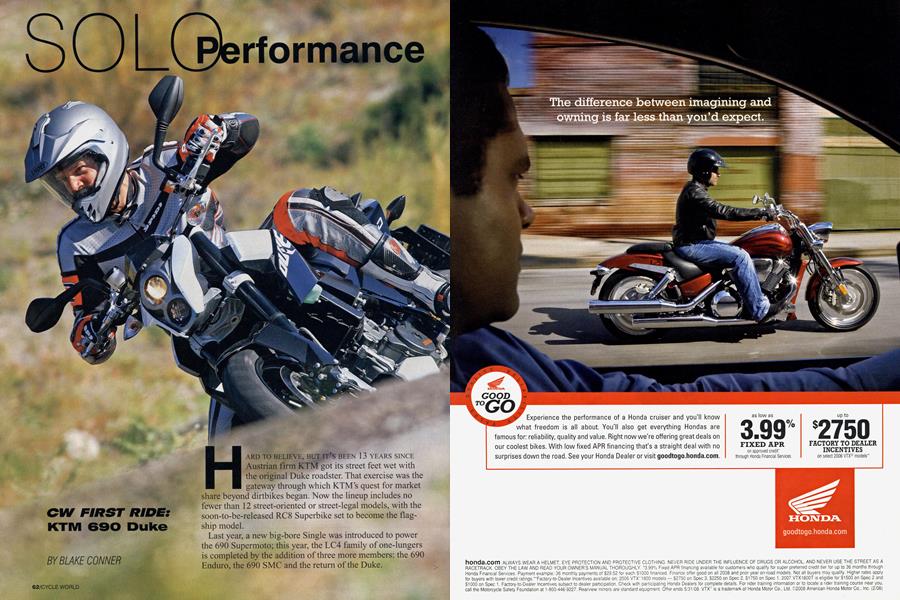

SOLO Performance

CW FIRST RIDE:

KTM 690 Duke

BLAKE CONNER

HARD TO BELIEVE, BUT IT’S BEEN 13 YEARS SINCE Austrian firm KTM got its street feet wet with the original Duke roadster. That exercise was the gateway through which KTM’s quest for market share beyond dirtbikes began. Now the lineup includes no fewer than 12 street-oriented or street-legal models, with the soon-to-be-released RC8 Superbike set to become the flag-ship model.

Last year, a new big-bore Single was introduced to power the 690 Supermoto; this year, the LC4 family of one-lungers is completed by the addition of three more members: the 690 Enduro, the 690 SMC and the return of the Duke.

When it comes to pure corner-carving, the 690 Duke could prove hard to beat. An ultra-lightweight chassis and upright streetfighter riding position with wide moto-style bars are the right ingredients to tear up just about any tight road. The Duke may not have the power of other competitors’ naked Twins, Triples or Fours, but the combination of its feathery 326-pound claimed dry weight and 65-horsepower motor should put a smile on any backroad buckaroo’s face.

The new liquid-cooled, 654cc, four-valve, dry-sump engine features a counterbalancer and is fuel-injected, making it a very civilized street machine. A couple of other features like adjustable ignition mapping (more on that later) and a slipper clutch give the Duke a very sporting character. All four bikes in the LC4 range share essentially the same engine, but differences can be found in the Duke’s larger airbox and higher-flow, catalyzer-equipped “under-floor” exhaust that raises power slightly over the Enduro and SMC models. The cylinder head has been updated slightly from last year’s Supermoto, a new cam actuating the four valves via rocker arms.

On the open road, there isn’t exactly a surplus of power, but the engine is very smooth with only a small amount of vibration apparent in the upper revs. Fuel-injection response from the hybrid electronic/cable setup could use some refinement, though. The rider’s wrist turns the grip, which does the traditional chore of opening the butterfly, but the computer in the ECU tells an electronic servo how quickly to do so. Opening the throttle around 4000 rpm usually resulted in a slight stumble amplified by a touch of driveline lash. It also depended on which of the two adjustable ignition maps was selected.

The Duke’s switchable map system varies from those on Suzukis and the Benelli TnT because it’s not accessed via a handlebaror dash-mounted button. To change the mapping on the Duke, you reach in between the trellis frame rails and pull a small black rheostat-looking device from its rubber-covered housing and set it to one of two maps (on the Enduro/SMC models, the switch is under the seat). The difference in power output is quite noticeable but not as dramatic as on the Enduro and SMC, which have a third map for low-octane fuel if you happen to be dual-sporting in, say, Baja and get some less-than-optimal petrol.

Throttle response was more aggressive and instant in the “high” mode and felt mapped slightly better. On the Duke, I wanted all the power it could give me all the time, but the tamer power curves came in handy when riding the Enduro and SMC in loose-traction situations-a pain, though, having to stop to switch map settings.

On the lightly patrolled Spanish expressways, the Duke could easily pull an indicated 180 kph (112 mph), a bit much on a bike without a fairing of any significance; cruising in the 85-mph range was much more comfortable. Either way, there were moments when I had to remind myself that I was riding a Single, especially squirting out of corners on tight mountain roads where the power deficit-compared to multicylinder bikes, anyway-didn’t feel like an issue.

Although there is a definite family resemblance between the three LC4s, the Duke’s chassis is unique. Featuring a stiffer trellis frame, it also has a more rigid and very long pressure-diecast aluminum swingarm with external ribbing. Rear suspension is handled by a WP shock with piggyback reservoir and Pro-Lever linkage providing 5.5 inches of travel. The use of a linkage allowed engineers to make the chassis more compact and improve packaging. Up front, a 48mm inverted WP fork with 5.5 inches of travel is valved for a sporty ride. Diecast Marchesini wheels wear Dunlop Sportmax tires in 120/70ZR17 front and 160/60ZR17 rear sizes. The single radial-mount front Brembo caliper features four pistons/pads and bites down on a 320mm rotor, pumped by a radial master cylinder and braided stainless lines. On such a light bike, the setup provided serious stopping power with zero fade.

Probably the most interesting aspect of the Duke is how engineers chose to package components for ideal weight distribution and optimal handling. We’ve mentioned the under-engine stainless-steel exhaust, but there’s also a largevolume airbox mounted beneath the rider’s butt, taking air in from the tailsection a la motocross bikes. The battery is mounted just behind the frame’s steering head. On the Duke, 4.8 gallons of fuel is carried in the traditional over-engine location and a conventional subframe is used to support the rider and passenger. That differs from the Enduro/SMC’s underseat fuel tank that has a secondary function as the saddle support.

KTM chose a nice location in southern Spain for introduction of the three bikes. A twisty route through the Sierra Alhamilla Mountains near Almería provided miles of tight roads to sample the Duke. The bike feels anything but entrylevel the second you hit the curves. The firm, well-damped WP suspension is tailored for aggressive sport riding. The bike flicks into and out of corners far better than any traditional repli-racer with stubby clip-ons could dream of. Anyone coming from a traditional sportbike will have to adjust to how nimble this bike is; very little pressure on the handlebar results in instant steering. I found myself oversteering a few times early in the ride. Feel from the front end is excellent and grip from the Dunlop tires very good.

A huge 102mm piston with a relatively high 11.7:1 compression ratio could make compression braking a bit of an annoyance, but the excellent slipper clutch eliminates any of those negative effects before they reach the rear wheel. Banging downshifts through the six-speed box-to keep the Single thrumming in its sweet spot-results in ultra-smooth comer entries, even if the gearbox itself isn’t quite up to Japanese sportbike standards.

Thankfully, the Duke features a different seat than its LC4 siblings, as those MX-style saddles aren’t the most comfy for the long haul. Speaking of the seat, it can be ordered in two heights; standard is the 34.5-incher, which is rather high compared to traditional sportbike measurements of around 32. A second seat, 3A of an inch taller, is also available, thereby alienating the inseam-challenged altogether.

Minimalist bodywork includes a small upper fairing that houses stacked projector-beam halogen headlamps and a small chin spoiler just in front of the exhaust. The dash assembly is a combination of an analog tachometer, LCD speedo and information screen. Two colors will be offered: traditional KTM orange-and-black and a more conservativelooking white-and-black combo.

The Duke may not be for everyone, especially at the $9498 asking price (blame the weak dollar), but it offers fun and impressive performance for those searching for pure handling nirvana. As an urban-assault weapon, apex killer or lightweight track bike, the Duke will surely satisfy those who can appreciate the fact that great things can come in small, simple packages.