A Man in La Mancha

Retracing the very real route of the fictional Don Quixote

JEFF BUCHANAN

“Down in a village of La Mancha, the name of which I have no desire to recollect, there lived, not long ago, one of those gentlemen who usually Leeps a lance upon a racL, an old bucLIer, a lean stallion and a coursing greuhound.” — Cervantes, Don Quixote

THAT IS HOW MIGUEL DE CERVANTES INTRODUCED Don Quixote to the world in 1605. In scribing those words, Cervantes ushered in one of the most treasured and enduring fictional characters in literature. The resulting manuscript, Don Quixote de La Mancha, is regarded as the first modern novel and changed the landscape of publishing. It has since been translated into more languages and read by more people than any other book, save the Bible. Not a bad legacy for a story the penniless author began as a simple serial while serving time in debtor’s prison.

It’s also a book that has something to say to any motorcycle rider who has ever ventured beyond city limits.

My own personal relation with Quixote began when I was a kid. My father had become enamored of the book with its engaging theme of an aging, slightly mad idealist who sets off across La Mancha seeking adventure, mistaking peasants for kings and windmills for giants. Dad used it, to some degree, as a blueprint for how to live his own life. The result, for us children anyway, was a wonderfully entertaining roller-coaster ride of chasing farfetched dreams that, due to our innocence, had us pleasantly ignorant of his struggles and pitfalls. My father passed away in 2004 without relinquishing his optimism. It was time for me to read the book.

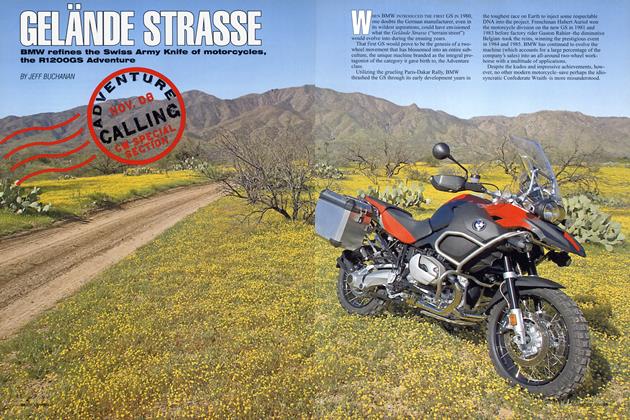

The novel was cracked in flight over the Atlantic, the first chapters unfolding at 35,000 feet-the story thoroughly engaged upon touchdown in Barcelona 11 hours later. I’d come to Spain in homage of my father, intent on retracing the route of Cervantes and reading the book in the realm where it was created. The mount of choice for this most personal of sojourns was that two-wheel icon of adventure, a BMW R1200GS. Once the GS’s wheels were turning on Spanish soil, the kilometers clicking by, carrying me deeper into the interior, the pages of the book were devoured at every opportunity with increasing voraciousness.

Don Quixote, the novel, having just celebrated its 400th anniversary, remains increasingly pertinent, seemingly more relevant today than when it was first written. Quixote, obsessed with adventure books and fanciful tales of knighthood, grows somewhat disenchanted with what he perceives as diminishing values and fading decency in the world, and sets out to recapture the romanticism and chivalry of a bygone era. He dons tarnished armor and, astride his steed Rocinante, sets out on a noble quest as a self-proclaimed knight-errant accompanied by a devoted squire, Sancho Panza, on his donkey. On the outskirts of Cuenca, gateway to La Mancha, the book had worked its magic, seducing me with its whimsy, and the GS, of course, was rechristened Rocinante.

There are numerous locations throughout La Mancha (the region south and east of Madrid) that hold genuine significance with relation to the book. There is Alcala de Henares, birthplace of Cervantes, and the village of Puerto Lapice, where Quixote persuaded a local innkeeper to grant him knighthood. El Toboso, the village where Dulcinea, Quixote’s ladylove, lived-inspiration for his quests and source of his heartache (despite the two never meeting)-is an essential stop. In fact, the Spanish Tourism Board has created “The Route of Don Quixote,” covering 600 miles, a hundred villages, countless museums and numerous points of interest from the book. I was here to see the most iconoclastic: the windmills.

Quixote’s infamous assault on what he perceived as multiarmed giants has become perhaps the most famous of his misadventures. The episode is so well-known it has entered international vernacular as the proverb, “Tilting at windmills,” describing an act of futility. The word “quixotic,” meaning to take a romanticized view of life, was also born from the book. Without a doubt, Quixote is the quintessential romantic. His tireless pursuit of unattainable ideals and lofty ambitions result in delusions and mishaps, rendering him a sad, somewhat tragic character with whom the common man seems to identify more readily than traditional, perfect heroes.

Meandering the backroads and villages of La Mancha, I delved deeper into the novel. In the small bars and cafés of these lazy enclaves, deeply browned Spaniards-with plenty of silver in their smiles-would patiently listen to my abysmal attempts at their language, faces brightening when they discerned my quest was retracing the route of their beloved Don Quixote. Asking after their local hero was like being in possession of the key to the city. Locals would then eagerly point me to the nearest Quixote artifact or point of interest.

And that’s the way I traipsed about the countryside, preparing myself for arrival at Capo de Criptana, where a group of whitewashed windmills from the 15th century have stood sentinel against the passing of time. There are but a handful of these structures left, sprinkled about La Mancha, most in disrepair. The windmills at Criptana, however, the actual “giants” Cervantes immortalized, are preserved as a national treasure.

Ironically, as the windmills that powered industry 500 years ago are on decline, modern versions are cropping up, designed to transform wind into electricity. These forests of modernity line mountain ridges to create a 21st-century rendition of the imposing army > Quixote took on. It’s easy to see how a man, unhinged from reality and reason, could take them as monsters. This is, after all, a realm that ignites the imagination.

Miguel de Cervantes’ life was plagued by struggle and misfortune. Despite the success of the novel, he never realized any great monetary wealth. A contemporary of William Shakespeare, the two men would die on the same day. Cervantes could never have imagined that the manuscript he had tucked under his arm as he traveled through La Mancha was going to have such a profound impact on the world.

I arrived in Criptana just past mid-day. The sun can be serious business here, when the months of June, July and August turn the region into the frying pan of Spain. Locals have a saying: “La Mancha, nine months of winter, three months of hell.” My personal adventure was undertaken in perhaps the best of times, September, when the weather is mild and the waves of summer tourism have abated. As I ambled up the winding road, weaving through the narrow alleys of the village, I caught fleeting glimpses of the ancient windmills through the buildings. The town fell away, introducing a plateau spreading out before me, a dozen whitewashed windmills spread over the rocky, windswept terrain.

A good deal of time was spent in the company of the windmills. The story-and memory of my father-had come to life for me. I finished the novel sitting at the base of one of the giants, the setting sun casting deepening shades of orange and red on the stucco facades. There is magic here. Cervantes saw this and managed to capture it on the pages of the novel with effect most writers can only dream of.

Four hundred years after its publication, Don Quixote continues to

find new audiences and is revisited regularly by passionate devotees. If ever there was a literary personage that possesses the wanderlust so prevalent in the consciousness of motorcyclists, it is Quixote. If the knight-errant were with us today, he would undoubtedly be riding a motorcycle. The novel is essentially a road/buddy movie in the classic sense; two guys searching for purpose and adventure in an indifferent world. The fact that they never achieve their goals isn’t exactly important. The importance is that they went. In this regard,

Don Quixote is a motorcyclist’s story. Because let’s face it, half of our trips on motorcycles hide behind some vague excuse, some masquerade of purpose. The magic is in the going.

Sitting by the windmills, I realized that what had started out as a simple motorcycle trip had, in fact, evolved into a deeply cathartic journey. I suddenly understood my father’s love for Don Quixote, Man of La Mancha, because the fictional knight’s flaws and missteps in life make him wonderfully real, wonderfully human, suggesting you needn’t win, you needn’t totally succeed, in order to find the romance and magic in life. That’s the theme my father embraced in his own sojourn, inadvertently handing that simple wisdom down to me.

As I head out of Toledo toward Madrid, fortified with a cortado (double espresso with milk), I find myself riding alongside a whining little Derbi 125cc, its two-stroke motor belching smoke. The rider is a rotund Spaniard, his browned face protruding from a half-helmet.

As I pull away, for a brief moment I imagine our silhouette against the blushing La Mancha sky must look strangely familiar...

Jeff Buchanan, former Team Maico MX mechanic, indie film producer and award-winning commercial director, co-founded Robb Report Motorcycling and is now settled into a career as a freelance writer. This is his first Cycle World story.