SERVICE

PAUL DEAN

Movie reviews

Q I just saw the latest Indiana Jones flick and was distracted by what looked like front disc brakes on the Harley being ridden by the kid. Harley aficionados out there can no doubt cite the model number, but didn’t disc brakes first appear on bikes in the early 1970s, long after college professors stopped wearing bow ties? Dominic Haigh Posted on www.cycleworld.com

A Although disc brakes for motorcycles were available in the aftermarket for a few years beforehand, the 1969 Honda CB750 Four is generally acknowledged as the first production bike to have a disc brake. It rolled off the assembly lines with a single hydraulic front disc arrangement but retained a rod-operated drum brake at the rear. Harley-Davidsons, meanwhile, didn’t get discs until 1972.

You shouldn’t be surprised to see motorcycles misrepresented in the movieseven a big-buck film like the one in question. After all, I’ve seen countless movies in which bikes like Suzuki DR350 dual-purpose four-strokes and Ducati V-Twins have distinct inlineFour or two-stroke Single exhaust notes. And when Schwarzenegger steals a Harley Fat Boy (Terminator 2: Judgment Day) that just happens to have a scabbard for stowing a shotgun he took from someone else, then jumps that same bike off a 12-foot-high wall without the slightest damage, all bets are off. Remember, it’s fiction-right down to the authenticity of practically everything you see.

Gear-shifting hopscotch

Q I have a 2006 Kawasaki ZX-14, and thanks to its great torque, I find myself upshifting 2 or 3 gears at a time during easy cruising. Am I possibly doing any damage to the transmission by shifting this way? Richard Krebs Pensacola, Florida

A Not unless you are shifting very slowly. One of the several factors that can cause transmission damage is a large difference in speed between the gears as they are being engaged. When a shift is made, one gear of an adjacent pair is slid sideways on its shaft so its engagement dogs can mate with those of the other gear, which cannot move sideto-side. Even though both of those gears reside on the same shaft, one is mechanically connected-via the transmission output shaft and final drive-to the rear wheel; the other gear is connected-via the mainshaft, the clutch and the primary drive-to the crankshaft. While the clutch is disengaged during a shift, however, that latter gear is connected only to the inner clutch hub via the mainshaft. When the transmission is in any given gear, the two mating gears for that ratio are locked together and spinning at the same speed; but as the tranny is upshifted or downshifted, the gears for the “new” ratio are turning at different speeds. And since one of those gears is being turned by the rear wheel, which has the mass of the entire bike and rider driving it, that gear is not likely to change speeds during the shift; the other gear, driven only by the momentarily freewheeling inner clutch hub, will be the one that has to suddenly slow down or speed up.

When the speed of those two gears as they engage is relatively close, the impact between their mating engagement dogs is small. This allows the dogs to engage smoothly, easily and quietly, since the gear connected to the inner clutch hub does not have to change speed to any significant degree.

But when the speed differential is large, not only is there a sizable impact between the two gears’ engaging dogs, which can accelerate their rate of wear, the dogs also tend to reject one another for a few revolutions. This not only rounds off the edges

of the dogs, it deflects

the movable of the two gears sideways, which can bend its shift fork, possibly enough to gouge the thrust pads machined on the gear end of the fork. That kind of wear soon leads to missed shifts and a transmission that jumps out of gear.

I tell you all this to help you understand that the more slowly you make your “skip” shifts, the greater the speed differential between the mating gears. But if you shift in rapid succession and hear no unusual clunking along the way, the transmission should not suffer any damage.

Kind of a sprag

Q My 2003 Aprilia Mille has a problem. When I hit the starter button, sometimes the engine fires up, and sometimes the starter motor spins but doesn’t turn the engine over at all. When the starter just spins, repeated attempts with the button usually have no positive effect, although if I keep trying long enough, the starter occasionally will “catch” and fire up the engine. A Yamaha rider helped me bump-start my bike at a gas station one day when the engine wouldn’t start, and he said the problem is with the sprag clutch. I’ve never heard of such a thing. Was he correct or just pulling my leg? C.J. Simmons Bellevue, Washington

A That Yamaha rider’s diagnosis was spot-on. A sprag clutch is a mechanism that only allows rotation in one direction between two concentric components. Most electric-start motorcycle engines use a sprag somewhere between the starter and the crankshaft, and even the slipper clutches that are being incorporated on a growing number of bikes use a variation on the sprag clutch concept.

Sprag clutches generally look kind of like roller bearings, with an outer “race” built onto one of the two affected components (the crankshaft, for instance, in an electric-start system) and an inner race connected to the other (such as the starter motor). Instead of round rollers, which bike engines used years ago, most sprags these days have dogboneor figure-eight-shaped elements held in place by light springs. The elements fit between the races at a slight angle so that when the outer race on our hypothetical example is turning and the inner race is not (which is the case when the engine is running), the tilt of the elements lets them slip harmlessly across both races’ surfaces, having no effect on the inner race. But when the inner race is turning and the outer one is not (such as when the engine is stopped and the starter motor engages), the spring-loaded elements “stand up” and wedge themselves between the races. This makes both races turn at the same speed until the rpm of the engine (outer race) exceeds the rpm of the starter motor (inner race).

Feedback Loop

Q In the “Milwaukee melody” letter in the July Service, you told the letter’s writer, Chris Graham, that “your friend is completely wrong” in his claim that the distinctive of a Harley-Davidson is caused by its ignition timing. You then proceeded to imply that a Harley engine has a distinctive sound because it is a 45-degree Vee while the Ducati is a 90-degree Vee. In itself, there’s really not that much difference between the two. The reason the Harley has a distinctive sound, which you did not even bring up, is because its ignition timing is 45/675 degrees, whereas the Ducati’s is 270/450. The Harley, as it is timed, sounds and runs more like a Single than a Twin while the Ducati is much closer to even-firing. So, Graham’s friend was not “completely wrong” at all. John Roth Placitas, New Mexico

A l’m not trying to be argumentative, John, but you also are mistaken, as are quite a few other people who have written in response to that same letter. First of all, you seem to be confusing “ignition timing” with “firing intervals.” Ignition timing refers to the precise point in a crankshaft’s rotation at which the sparkplug ignites the fuel mixture in any given cylinder; that event is expressed in degrees Before, At or After Top Dead Center, and it has nothing to do with the firing intervals between cylinders, which is the subject matter in question here.

You also are in error in regard to those intervals. On a Harley Big Twin or Sportster, they are 315/405, not 45/675. After front-cylinder ignition, the crankshaft rotates 315 degrees (360 degrees minus 45 degrees) before the rear cylinder fires. The crank then rotates 45 degrees as its single crankpin passes the front cylinder, which is now ending its exhaust stroke, continues another 315 degrees to the rear cylinder, which by then is also wrapping up its exhaust stroke, and another 45 degrees to fire the front cylinder again. That’s 45 plus 315 plus 45, which is 405 degrees. So, with only 90 degrees of difference in its firing intervals (405/315), the Harley’s engine actually is closer to even-firing than the Ducati’s, which, with 180 degrees of differential (270/450), has twice the unevenness.

Some flat-track race tuners modify the cams and ignitions on V-Twin engines to make them fire at the highly uneven intervals you describe. The results are 45/675 degrees on 45-degree Vees and 90/630 on 90-degree engines. This does indeed make them more like a big Single, affording them a long period between combustion events to help the rear tire gain traction on dirt.

In your Aprilia, something is causing the elements to skid along both races rather than wedging between them when the starter motor is engaged. The springs that hold the elements in place could have broken, or perhaps the sprag assembly is in the process of disassembling itself. Whatever the problem, you’ll need to have the sprag either repaired or replaced. Be forewarned, though, that this is not a cheap fix; the parts alone (the outer race, which is part of an entire starterspeed reduction gear, plus the inner race and the 20-element sprag unit) are in the neighborhood of $800, and R&R calls for a couple of hours of labor. So, don’t be shocked if the final bill is around a grand.

Five into six won’t go

Q I have a 2006 Harley-Davidson FLHTI Electra Glide Standard purchased new in February of 2006, and it now is showing just over 60,000 miles. It is my only means of transportation, and as indicated by the mileage, I do a lot of longdistance touring. I would like my fivespeed bike to have the advantage of a six-speed transmission without the expense of actually purchasing a sixspeed, so my question is: Does anyone make a rear-wheel pulley a tooth or two smaller that would give me the effects of increased speed and lower rpm? Richard R. Ray Maricopa, Arizona

A Sorry, Ray, but you are asking the impossible. There is no way you can have the advantages of a six-speed transmission with your existing fivespeed. First of all, there are two different types of FI-D six-speed gearboxes: Some have a direct-drive sixth gear, which means the ratio in sixth is 1:1, just as it is on your five-speed; and some are overdrive six-speeds in which fifth gear is direct but sixth is taller by as much as 16 percent, depending upon the brand of box. Direct-drive six-speeds have a lower first-gear ratio so that you can use taller final or primary gearing for lower rpm on the road but still have a deep enough first gear for easy dead-stop starts. Overdrive six-speeds have about the same first-gear ratio as a five-speed but with the taller sixth for more-relaxed cruising. If you install taller final gearing on your five-speed FL (and you would need at least four fewer teeth on the rear pulley to make a significant difference, not just one or two), the cruising rpm would be lower but pulling away from a dead stop, especially on an uphill with loaded bags and a passenger, would be more difficult and hard on the clutch.

If you decide to do this anyway, change the transmission pulley, not the rear one. Changing the rear involves buying a shorter belt, as the adjusters on the swingarm do not have enough range to compensate when the stock belt is wrapped around a 4-tooth-small er pulley; this also means the entire primary drive and swingarm have to be removed for belt replacement. But if you swap the stock 32-tooth transmission pulley for a 34, you get about the same overall gearing as you would with a 4-tooth-smaller rear, and the existing belt will work; and although the primary drive would still need to be removed for installation of the pulley, the swingarm won’t, since the stock belt is being retained.

Either way, this is not a do-it-yourself job; it requires special tools and reasonable experience working with HarieyDavidson primary drives and swingarmmounting systems. Expect to pay between 3 and 4 hours’ worth of labor charges for the front-sprocket swap, about an hour more for the rear.

Wear, oh wear

Why do the drive chain and sprocket assemblies on motorcycles wear in a manner that produces tight spots and loose spots in the chain as it rolls? Shouldn’t they both wear out uniformly? And how much of a difference between the tight and loose spots means that the chain is worn out-or would it be that the sprockets are worn out? I am currently observing this irregular wear on a Suzuki V-Strom 650 but have seen this pattern on every chain-driven streetbike I’ve ever had. Tom Hund Redwood City, California

A There are several reasons that chains and sprockets can wear unevenly. First of all, you might think that the delivery of thrust from engine to rear wheel is a smooth flow of power, but your driveline would disagree. The engine speeds up very slightly with each combustion stroke, then slows down until the next firing; and while those changes in speed usually are impossible for the rider to perceive, they impose ever-varying taut-slack-taut loads on the chain. To a lesser degree, the same thing happens in reverse on trailing throttle as the rear wheel pushes the pistons through their compression cycles and makes the cams overcome valve-spring pressure. Next time you ride alongside a chaindriven motorcycle, watch the chain and you’ll see that even when the bike is moving at a steady speed and constant throttle setting, at least some part of the chain is usually fluttering up-and-down. With single-cylinder engines that have almost two crank revolutions between combustion events-or V-Twins with irregular firing intervals-the fluctuations are even more pronounced.

These fluctuations change according to engine speed, road speed, gear selection, throttle opening and riding style, and they are not synchronized to the ratio of the final-drive gearing. Consequently, the cumulative wear they impose on the chain and sprockets almost can’t help being uneven.

Other factors compound this basic wear pattern. Water and dirt usually do not accumulate in equal amounts all around the chain and sprockets; a little more corrosive material in one place or another will cause uneven wear. Plus, after a ride when the chain is warm, some part of it cools on the straight runs between sprockets while the rest of it does so while wrapped around the sprockets. Depending upon the nature of any contamination that has accumulated on the chain, as well as the lubrication on or in it, that difference can easily cause a slight kink that usually goes away during the next ride but, in the process, still causes a little extra wear in those kinked areas. And once a wear pattern starts in one place on the chain or sprockets, the rate of wear tends to accelerate more there than on the rest of the chain.

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find workable solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology? Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1) Mail a written inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631-0651 ; 3) e-mail it to CW1Dean@aol.com; or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com, click on the “Contact Us” button, select “CW Service” and enter your question. Don’t write a 10-page essay, but if you’re looking for help in solving a problem, do include enough information to permit a reasonable diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

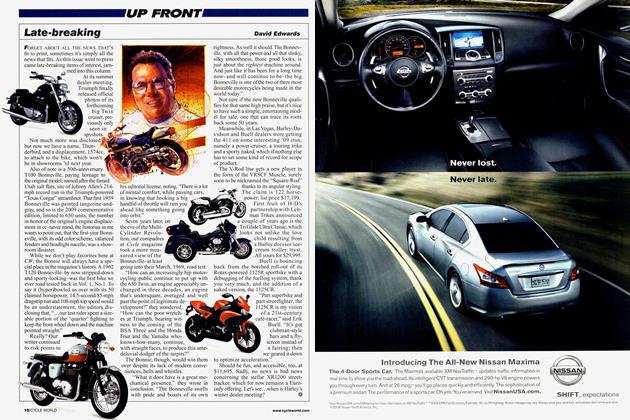

Up Front

Up FrontLate-Breaking

October 2008 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRiders On the Storm

October 2008 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAma Evolution

October 2008 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2008 -

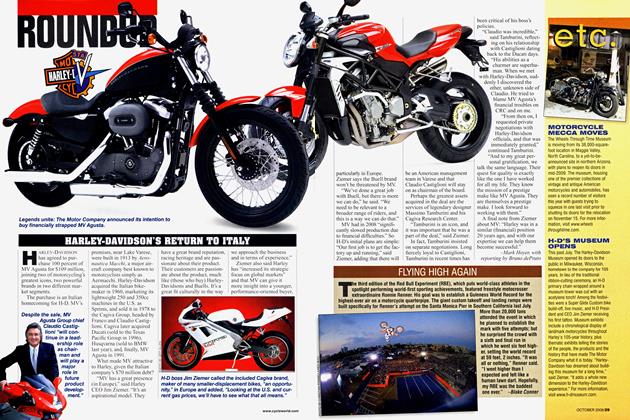

Roundup

RoundupHarley-Davidson's Return To Italy

October 2008 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupFlying High Again

October 2008 By Blake Conner