AMA Evolution

TDC

Kevin Cameron

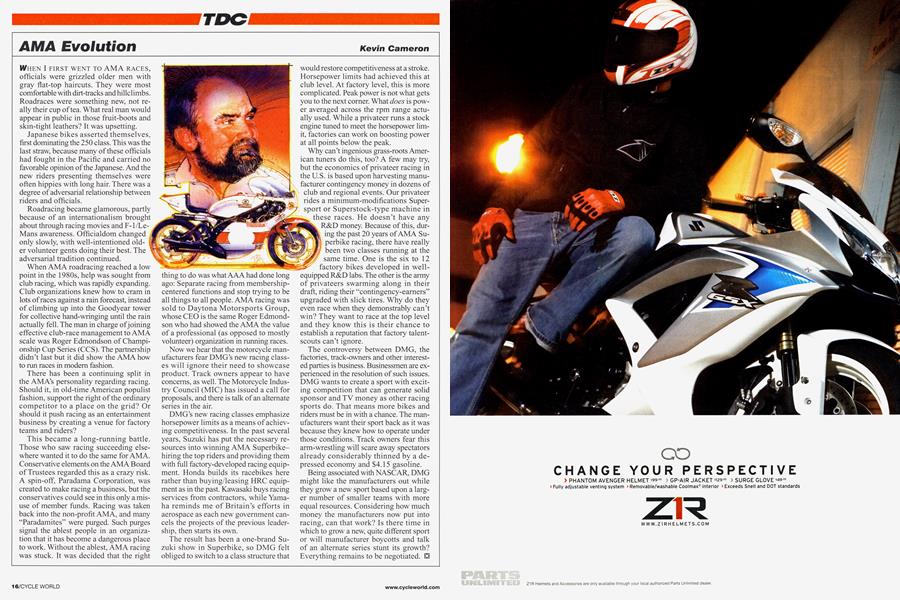

WHEN I FIRST WENT TO AMA RACES, officials were grizzled older men with gray flat-top haircuts. They were most comfortable with dirt-tracks and hillclimbs. Roadraces were something new, not really their cup of tea. What real man would appear in public in those fruit-boots and skin-tight leathers? It was upsetting.

Japanese bikes asserted themselves, first dominating the 250 class. This was the last straw, because many of these officials had fought in the Pacific and carried no favorable opinion of the Japanese. And the new riders presenting themselves were often hippies with long hair. There was a degree of adversarial relationship between riders and officials.

Roadracing became glamorous, partly because of an internationalism brought about through racing movies and F-l/LeMans awareness. Officialdom changed only slowly, with well-intentioned older volunteer gents doing their best. The adversarial tradition continued.

When AMA roadracing reached a low point in the 1980s, help was sought from club racing, which was rapidly expanding. Club organizations knew how to cram in lots of races against a rain forecast, instead of climbing up into the Goodyear tower for collective hand-wringing until the rain actually fell. The man in charge of joining effective club-race management to AMA scale was Roger Edmondson of Championship Cup Series (CCS). The partnership didn’t last but it did show the AMA how to run races in modem fashion.

There has been a continuing split in the AMA’s personality regarding racing. Should it, in old-time American populist fashion, support the right of the ordinary competitor to a place on the grid? Or should it push racing as an entertainment business by creating a venue for factory teams and riders?

This became a long-running battle. Those who saw racing succeeding elsewhere wanted it to do the same for AMA. Conservative elements on the AMA Board of Trustees regarded this as a crazy risk. A spin-off, Paradama Corporation, was created to make racing a business, but the conservatives could see in this only a misuse of member funds. Racing was taken back into the non-profit AMA, and many “Paradamites” were purged. Such purges signal the ablest people in an organization that it has become a dangerous place to work. Without the ablest, AMA racing was stuck. It was decided that the right thing to do was what AAA had done long ago: Separate racing from membershipcentered functions and stop trying to be all things to all people. AMA racing was sold to Daytona Motorsports Group, whose CEO is the same Roger Edmondson who had showed the AMA the value of a professional (as opposed to mostly volunteer) organization in running races.

Now we hear that the motorcycle manufacturers fear DMG’s new racing classes will ignore their need to showcase product. Track owners appear to have concerns, as well. The Motorcycle Industry Council (MIC) has issued a call for proposals, and there is talk of an alternate series in the air.

DMG’s new racing classes emphasize horsepower limits as a means of achieving competitiveness. In the past several years, Suzuki has put the necessary resources into winning AMA Superbikehiring the top riders and providing them with full factory-developed racing equipment. Honda builds its racebikes here rather than buying/leasing HRC equipment as in the past. Kawasaki buys racing services from contractors, while Yamaha reminds me of Britain’s efforts in aerospace as each new government cancels the projects of the previous leadership, then starts its own.

The result has been a one-brand Suzuki show in Superbike, so DMG felt obliged to switch to a class structure that would restore competitiveness at a stroke. Horsepower limits had achieved this at club level. At factory level, this is more complicated. Peak power is not what gets you to the next corner. What does is power averaged across the rpm range actually used. While a privateer runs a stock engine tuned to meet the horsepower limit, factories can work on boosting power at all points below the peak.

Why can’t ingenious grass-roots American tuners do this, too? A few may try, but the economics of privateer racing in the U.S. is based upon harvesting manufacturer contingency money in dozens of club and regional events. Our privateer rides a minimum-modifications Supersport or Superstock-type machine in these races. He doesn’t have any R&D money. Because of this, durf ing the past 20 years of AMA Superbike racing, there have really 1 been two classes running at the same time. One is the six to 12 factory bikes developed in wellequipped R&D labs. The other is the army of privateers swarming along in their draft, riding their “contingency-earners” upgraded with slick tires. Why do they even race when they demonstrably can’t win? They want to race at the top level and they know this is their chance to establish a reputation that factory talentscouts can’t ignore.

The controversy between DMG, the factories, track-owners and other interested parties is business. Businessmen are experienced in the resolution of such issues. DMG wants to create a sport with exciting competition that can generate solid sponsor and TV money as other racing sports do. That means more bikes and riders must be in with a chance. The manufacturers want their sport back as it was because they knew how to operate under those conditions. Track owners fear this arm-wrestling will scare away spectators already considerably thinned by a depressed economy and $4.15 gasoline.

Being associated with NASCAR, DMG might like the manufacturers out while they grow a new sport based upon a larger number of smaller teams with more equal resources. Considering how much money the manufacturers now put into racing, can that work? Is there time in which to grow a new, quite different sport or will manufacturer boycotts and talk of an alternate series stunt its growth? Everything remains to be negotiated.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue