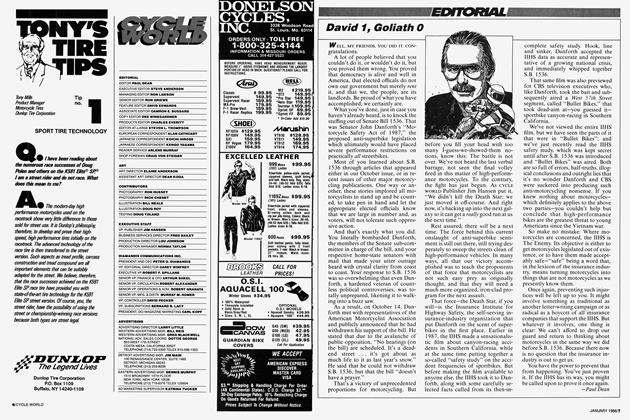

EDITORIAL

Turbocharging: Down But Not Out

I IT WAS MOTORCYCLING’S VERSION OF the free lunch. It was the promise of getting more from less, of having your cake and eating it, too. It was heralded as the wave of the future for motorcycles. Yet in the short span of just two years, it fizzled and died like a wet firecracker.

“It,” as if you haven't already guessed, was turbocharging, motorcycling’s hottest topic of three or four years ago. The magic of turbocharging, so the story went, would soon revolutionize motorcycle high-performance by allowing small-displacement bikes to perform like largedisplacement bikes. In no time at all, the ideal performance motorcycle would be a fairly ordinary-looking machine of around 500 or 550cc that could, on demand, accelerate like a liter-class hot-rod. These mediumdisplacement road-rockets would also squeeze upwards of 60 miles from a single gallon of gas, and handle like the nimble. 400-pound lightweights they inevitably would be.

Well, to say that things didn't quite go as planned for turbocharged motorcycles would be a gross understatement—like saying that Little Bighorn didn't exactly pan out the way Custer had hoped. Amidst great fanfare, all four of the Japanese manufacturers announced their initial entries in the brand-new turbo sweepstakes, each touting its high-tech, pressure-fed wunderbike as the greatest thing since the invention of gasoline. But the public apparently didn't agree, because turbocharged motorcycles proved about as popular as group tours of Three Mile Island. So rather than creating a performance revolution as promised, turbos instead became the Edsels of the motorcycle industry.

In all fairness, though, those turbo motorcycles weren’t as awful as their sales numbers might indicate. In many ways, they actually were quite appealing, exciting machines. And their failure in the showrooms was precipitated by unfortunate timing as much as by any mechanical or performance shortcomings they might have had. Turbos came along just as the world economy was beginning its meteoric plummet a few years ago, and it quickly became virtually impossible to sell motorcycles of any sort, let alone anything as exotic as a turbo.

Yet another crucial factor in the downfall of turbocharged motorcycles was their failure to live up to their advance billing. Somewhere along the line, the Japanese manufacturers lost sight of the original goal, that inviting promise of more performance from less motorcycle; instead, they seemed more intent on making corporate engineering statements with their turbo models than they did on building bikes that made sense. The result was a collection of turbobikes that answered many questions, but not the one that originally had been asked.

Honda, for example, deliberately designed its CX500/650 Turbo to serve as a rolling monument to that company’s engineering capabilities. It indeed was an impressive piece of work, but it also was so frightfully complicated that you didn't even want to think about who you'd get to repair it should it break, or how much those repairs might cost. Yamaha, on the other hand, wanted to be recognized for its more-practical engineering, and so built the 650 Seca Turbo, which —mechanically, at least—was comparatively simple and straightforward; but it also was barely able to outrun the normally aspirated 650 Seca on which it was based. And Suzuki chose to further its burgeoning reputation as a purveyor of excellent sporting machinery by giving its 650 Turbo a serious roadracing bent. The result was an awkward, uncomfortable bike that wasn't much fun to ride unless it was at radical lean angles and triple-digit speeds.

In the end, only Kawasaki came fairly close to fulfilling the promise of turbocharging by building what was, briefly, the fastest and quickest motorcycle on the streets. But to do that, the company had to use a 750cc engine, which in no way qualifies as “small.” And like all the others, Kawasaki’s 750 Turbo was overweight, overstyled and overpriced. So whatever turbos might have been, a free lunch they were not.

Despite their poor track-record, however, turbocharged motorcycles are not yet a dead issue. Turbo technology is marching ahead in quicktime outside of the motorcycle industry, where significant advances in turbocharger design and metallurgy continue to increase the efficiency of exhaust-driven forced-induction systems. There’s even some residual interest within the motorcycle industry, particularly at Honda, where development is ongoing in the quest for a turbocharged 250cc four-stroke Twin that can compete in roadracing—in the 500 G.P. class, no less.

That's an ambitious undertaking, even for Honda. But if such a machine does come into being, its development will elevate the state of the turbocharging art far beyond current levels. The obstacles Honda must overcome to make a turbocharged 250 four-stroke competitive with the astonishingly powerful 500cc twostroke G.P. racers—problems such as insufficient power output, throttle lag, and the weight a turbo system adds—are essentially the same ones that have to be dealt with before middle-displacement turbobikes will be able to live up to their promise.

If Honda has any success with its turbo racer, you can bet your boost gauge that a street version won’t be far behind, and that similar models from the competition will follow. And what is learned from the rigors of racing will help them all do it the right way. This time, the emphasis will be on the steak, not on the sizzle.

Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

August 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupYou Meet the Nicest People—On A Kodak?

August 1985 By Camron Bussard -

Roundup

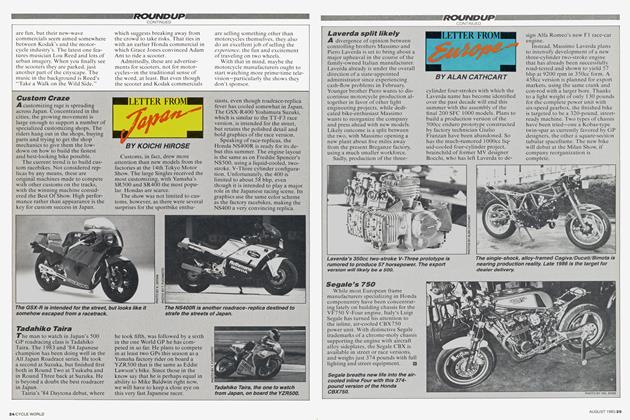

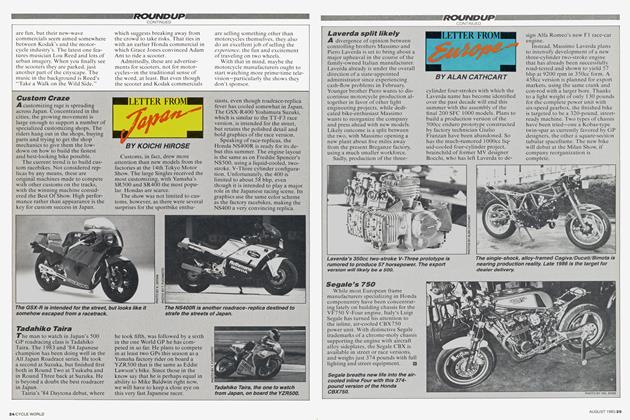

RoundupLetter From Japan

August 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

August 1985 By Alan Cathcart -

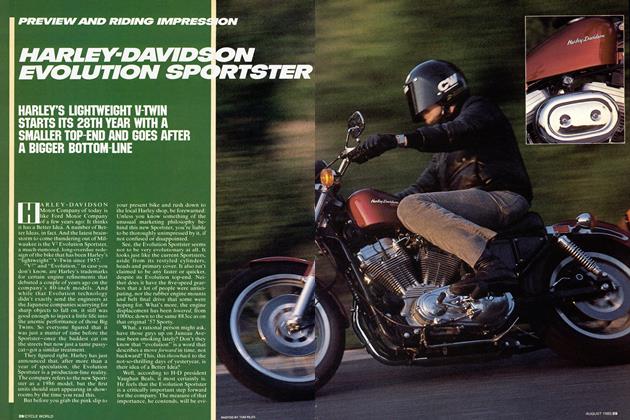

Preview And Riding Impression

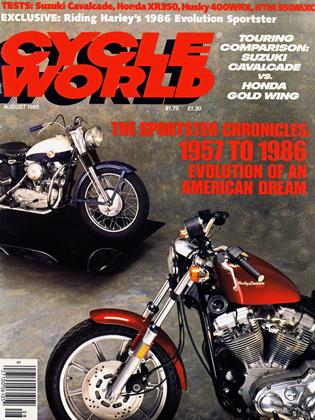

Preview And Riding ImpressionHarley-Davidson Evolution Sportster

August 1985