BLAST FROM THE PAST

RACE WATCH

A modern Vincent

GLENN FREEMAN

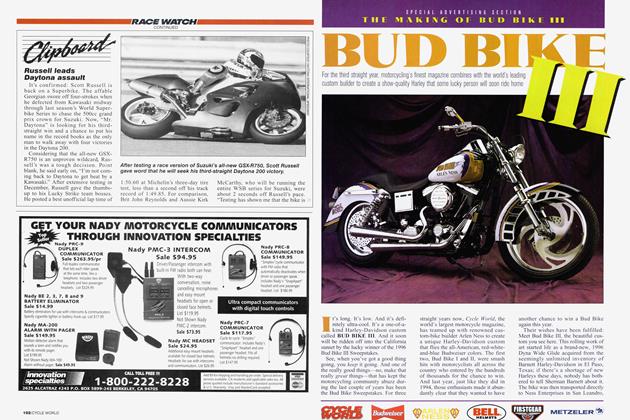

LAST MARCH, CRAIG MCMARTIN, REIGNING AUSTRALIAN ProTwins champion, rode a 1600cc Irving Vincent developed by Ken and Barry Horner of HRD Engineering to victory in the annual Battle of the Twins race at Daytona International Speedway. It was the first time in the history of the event that an Australian motorcycle piloted by an Australian rider had won the race. The achievement was all the more remarkable in that it was the team’s first entry in the class and McMartin had only a single 13lap practice session to set up the bike.

The Irving Vincent was purpose-built for Daytona by the Horners using essentially the same engine and frame layout as in the original Vincents that rose to prominence in the 1930s and ’40s. The marque reached its pinnacle in 1948 when Rollie Free, aboard a Black Lightning, rode into the record books after hitting 150 mph on the Bonneville Salt Flats. The Irving Vincent name was chosen by the Horners to honor the contribution Australian engineer Phil Irving made to Vincent: penning the original 500cc Single that powered the first Vincent-HRD and also the 47-degree V-Twin that brought the company so much fame.

Origins of the Irving Vincent go back four decades, when Ken had some success with a self-built 1300cc Vincent sidecar racer. Horner built his first sidecar in 1968, using a Norton frame powered by a Vincent engine he had acquired from an American named Eric Hawkinson. Hawkinson had dodged military service and fled to Australia, along with his brother. Both had been keen racers and members of the San Francisco Motorcycle Club, and they soon started building a NorVin (Norton frame, Vincent engine). When the U.S. government finally caught up with them, they sold the uncompleted project to Ken before being forced to return stateside. Horner finished the build and raced the machine for a number of years before retiring from competition and starting an engineering company, K.H. Equipment, leaving brother Barry to continue sidecar racing.

K.H. Equipment made its start manufacturing air starter motors for the mining and fuel-exploration industries. As a side venture, it also built an association with the Australian V8 Supercar series, developing a number of specialized race components for Holden teams. It was through this association that the Horners became involved with Irving, who, along with designing the original Vincent motor, also built the title-winning Repco race engine. About this time, Irving had inquired if Horner would perhaps be interested in building cylinder heads for Vincents, later dismissing the idea on the grounds that, “They’d never sell, anyway.” Barry recalls Irving on another occasion a few years before his death suggesting that someone should modernize the Vincent. “Before he died, he’d said it would be great if someone remanufactured them,” said Barry. This conversation stayed with the Horners. After taking a break from motorcycles in the early ’90s, they realized they still had a passion for two-wheelers and in 1999 made a return to the sport via increasingly popular classic roadracing.

“Some things just never leave you, and for us that was motorcycles,” said Ken Horner. As Barry describes it, both brothers had been keen to get into classic racing, “but we saw the only real way to do it properly was to start from scratch.”

Soon after the two made the decision to get back into building bikes, Ken was in the U.K. on business. While there, he began researching the availability of Vincent parts, such as crankcases and cylinder heads. “When I saw what was going on overseas, that there was no flexibility in making the sorts of changes we wanted, we decided we could build the parts ourselves at home,” he said.

Spanning some 16,000 square feet in the southeast Melbourne suburb of Hallam, the Horners’ workshop is no backyard chop shop. It’s equipped with highly specialized precision machinery, including CNC equipment, much of which they accumulated developing components for the V8 Supercars. Indeed, the Horners approached the engine build as if it were a quarter-size V8 Supercar engine.

Using a CAD package, Ken began drawing up plans for an engine based on the Vincent Black Lightning. Impressing upon people that the Irving Vincent is largely their own creation, not a reworked version of an existing motorcycle, has been a challenge.

“It’s not modified: It’s built from scratch!” exclaimed Ken. “One of the biggest problems is getting people to understand that it all comes out of Melbourne,” he sighed. With the exception of a number of components manufactured by aftermarket specialists, such as Öhlins, AP, Akront and Ceriani, it’s entirely their own machine.

But both emphasize that they have largely followed the same design as that of the original Vincent. The oil tank is part of the frame, and the triangulated swingarm is largely the same, albeit stronger to withstand the higher horsepower and improved rubber of the modern era. The modus operandi of HRD Engineering has been to take the same fundamental racewinning, record-breaking design incorporated in each Vincent since the earliest days and combine it with the high-strength, lightweight materials available today.

“They didn’t build it too bad back then,” said Ken, who acknowledges that though Vincent initially started out producing bikes for the racetrack, in the later years it was more about straight-line speed than cornering, with the bikes predominantly used for land-speed record attempts. “What we’ve been able to do is get the thing to handle, with changes in geometry and use of more modern materials,” he added.

While the Irving Vincent began with the sidecar that Barry used in winning the 2004 New Zealand Historic title, followed by a 1600cc machine produced in 2005 and a 1300cc classic racer of 2006, the actual bike that McMartin rode so successfully at Daytona this past March wasn’t started until September of last year.

According to Ken, “We were always going to build it but only decided last September to go to Daytona.” He had traveled to the U.S. for business and also took the opportunity to check out the classic racing scene, which he felt was somewhat underwhelming. “I found the classic roadracing a bit disappointing, with Battle of the Twins getting more recognition,” he said.

This event began in 1982 under the stewardship of the AMA, and over the years it has given rise to countless bikes that have achieved legendary status, from the Harley-Davidson XR-derived Lucifer’s Hammer through to the Britten VI000. Various Europeans have also had a number of successful tilts at the title, with Ducati’s then-prototype 851 winning the event in 1987. The only other Australian team to have taken a run at the BoTT was Vee Two, which in 1995 took its Ducati-based machine to a close-run third place.

The team of Aussies representing the Irving Vincent effort at the 2008 Daytona Bike Week comprised Ken and Barry Horner, rider McMartin and Ian Hopkins. Hopkins was the organizer and promoter for the crew, pulling together all the logistics, spare parts, tools and other bits and pieces that might be needed across to the other side of the world. He’s a business owner from Queensland and a devoted motorcycle fan from way back. He introduced himself to the Horner boys when they were running a bike at a Phillip Island classic event some years ago. He has been involved with the project ever since.

Hopkins was also responsible for the vehicle the crew drove into the Speedway on race day-a black Hummer with tinted windows and an Aussie flag draped proudly across the side. He was in awe of the sheer scale of Bike Week, describing the hundreds of massive motorhomes that lined the roads along with the gargantuan race trailers that many of the teams used to cart their supply of spare

bikes and parts. “There were probably 500,000 Harley-Davidsons there-they were everywhere!” he exclaimed.

McMartin was equally impressed with Daytona, the angle of the banking in particular. “It’s like no other track,” he said.

“You don’t get a sense of how steep the banking is before you’re actually on it.” Barry recalls the jubilation they felt when the Irving Vincent took the checkers in first place. “It was quite emotional to see Craig come over the line,” he said. “We’ve seen how much work went into it. We had a lot of old American blokes coming up to us with tears in their eyes, telling us, ‘You’ve just made racing history!

McMartin plans to stay with the team as it continues its successful campaign into the 2009 BoTT season. He is also looking forward to a new bike, which according to Ken will be an entirely different machine.

“This one is going into semi-retirement,” he explained, indicating they are reluctant to crash and maybe destroy the machine to which they now have a sentimental attachment. “It is its own legend now, so we need to keep it.”

As for next year’s event, he plans to build a four-valve version of the engine, replacing the two-valver that was run this year, along with making a number of changes to reduce the weight of the motorcycle. And while he’s reluctant to hint at how much power he expects the new one will put out-the current model produced around 165 hp on the dyno-he expects it will be a significant improvement.

There are also plans for what the Horners describe as a “very limited production run” of special editions of the Irving Vincent.

A prototype road model has been cobbled together, though Ken will say no more. He also unequivocally states they will never manufacture individual engines for separate sale because “it’s too easy for people to buggerize about with them and damage the brand.”

While the Irving Vincent is definitely a consuming passion for the Homer brothers, it is not a money-making venture. Their bread-and-butter earner is still the engineering business; the motorcycle project is merely an expensive side-venture. Given the brothers’ early success, though, one can only wonder what they could achieve if the Irving Vincent were to become their primary focus.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontLate-Breaking

October 2008 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRiders On the Storm

October 2008 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAma Evolution

October 2008 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2008 -

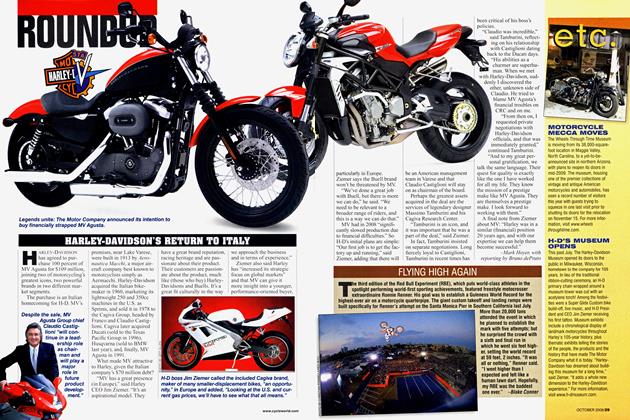

Roundup

RoundupHarley-Davidson's Return To Italy

October 2008 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupFlying High Again

October 2008 By Blake Conner