Twice around the Clock

RACE WATCH

The Nelson Ledges 24-Hour goes out in style

DON CANET

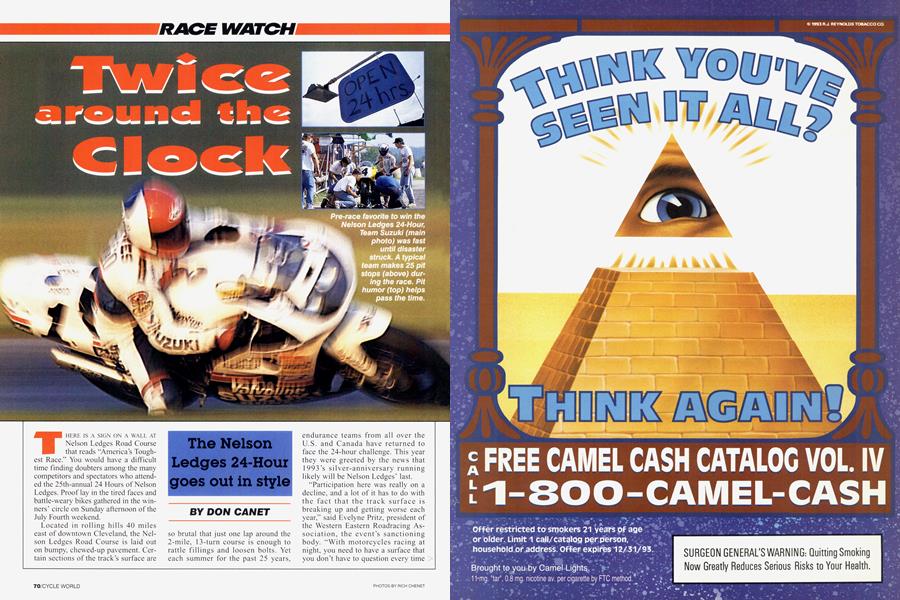

THERE IS A SIGN ON A WALL AT Nelson Ledges Road Course that reads “America’s Toughest Race.” You would have a difficult time finding doubters among the many competitors and spectators who attended the 25th-annual 24 Hours of Nelson Ledges. Proof lay in the tired faces and battle-weary bikes gathered in the winners’ circle on Sunday afternoon of the July Fourth weekend. Located in rolling hills 40 miles east of downtown Cleveland, the Nelson Ledges Road Course is laid out on bumpy, chewed-up pavement. Certain sections of the track’s surface are

so brutal that just one lap around the 2-mile, 13-turn course is enough to rattle fillings and loosen bolts. Yet each summer for the past 25 years, endurance teams from all over the U.S. and Canada have returned to face the 24-hour challenge. This year they were greeted by the news that 1 993’s silver-anniversary running likely will be Nelson Ledges’ last.

“Participation here was really on a decline, and a lot of it has to do with the fact that the track surface is breaking up and getting worse each year,” said Evelyne Pritz, president of the Western Eastern Roadracing Association, the event’s sanctioning body. “With motorcycles racing at night, you need to have a surface that you don’t have to question every time you go around.” Unless things are improved, WERA is set to move the event to a different venue in 1994.

This year’s Nelson Ledges took on increased importance because it was the only 24-hour event on the WERA schedule, following the decision to drop the 24 Hours West at Willow Springs Raceway in the Southern California desert. The nature of WERA’s scoring system-awarding points based on race distance

covered-and the fact that no other events on the 12-race schedule run beyond 6 hours, raised the stakes at this year’s Nelson Ledges 24-Hour to an all-time high.

“You have to do really well in the 24-Hour to win the championship and you can never predict what’ll happen to you here,” said John Ulrich, captain of Team Suzuki Endurance, the winningest endurance team in U.S. racing, with 89 endurance race wins, eight championships and seven 24hour wins, four of which came at Nelson Ledges. “You could win most every other race in the championship, but if you blow the-24 Hour you can end up not having the number-one plate,” said Ulrich.

I had experienced Nelson Ledges a few years ago, riding with Team Suzuki Endurance to an overall win in 1990. So, when Cycle World was contacted by Robert Nutt, team manager of Hall ‘N Still Racing, offering a ride aboard their Kinko’s Copies-sponsored Yamaha YZF1000, I thought, “Well, it wasn’t so bad last time.” Goes to show how winning distorts your perspective on things. I stuffed my gearbag with helmet, boots, leathers, gloves, rain suit, Rain-X, anti-fog and a kidney belt, all the essentials for a night out on the Ledges.

Pavement ripples and potholes aren’t the only elements that make Nelson such a test of endurance. Stories circulate the paddock of times when large toads, drawn by the asphalt’s warmth, descend upon the racing line during the night. In 1990, it rained nearly the entire race, turning the unpaved paddock into a quagmire. And I’ll never forget the exit of the Carousel-a long medium-speed sweeper leading onto the back straight. When wet, it has to be the slickest surface on the planet, and to make matters worse, it’s also about as rough as a mogul field. Screw up here and you end up sliding down a grassy slope and into a bog-a place from which bikes seldom return without the cooperative efforts of several burly men.

Die-hard spectators come from miles around to join in the weekend’s festivities, lining the infield fence with campers, motor homes, tents and scaffolds. When it isn’t raining during the night, heavy smoke produced by numerous campfires forms a fog-like curtain in front of your headlight. More than a few riders were startled as they completed their first night lap, seeing a billowing column of black smoke rising from beyond the bridge on the front straight. Had there been a horrible crash in the first turn? No, it was just the track’s old diesel-powered generator, merrily puffing away.

While there’s seldom a lack of action out on the track, the greatest drama often unfolds right in the pits. A stroll down pit row, day or night, reveals a carnival-like atmosphere, with teams working beneath colorful canopies. A small band of spectators behind a pit is usually the signal that a front-running team will be making a pit stop for fuel, rider change and fresh tires. A large group of on-lookers often means there’s a crew working frantically on a crashed bike. Crash repair was de rigueur this year. All three teams in the winners’ circle had overcome at least one get-off during the race.

In endurance racing, crashing is a roll of the dice: If you’re fortunate, you’re able to piece the bike back together and continue, but occasionally you throw craps and you’re out. Early in the race, my joining the Hall ‘N Still Kinko’s team looked like a good bet, as we were out front with a narrow lead over Team Suzuki Endurance by the end of the third hour. Then our luck crapped out. The front tire blew, resulting in a 130-mph crash that hospitalized lead rider Fritz

Kling. The bike had to be lifted out of the crash truck, its front end destroyed. One of the few parts that the Kinko’s team didn’t have a copy of was a YZF fork. I didn’t even get to ride.

With Kinko’s out of the running, it became a two-bike bout at the front, with the Heavyweight Superbikes of Team Suzuki Endurance and Virginia

Breeze Racing slugging it out for the title. By the eighth hour, Team Suzuki had some breathing room-a four-lap lead over the Yamaha FZR1000 of Virginia Breeze. Then the rough track surface delivered a low blow as the GSX-R1100 suffered front-tire failure-similar to our own-and crashed heavily in the Carousel. The same type Dunlop slick was involved in both incidents, reportedly a case of too many bumps for too long on a lightweight purpose-built racing radial. Team Suzuki lost nearly an hour recovering their bike and making the necessary repairs, bumping the defending champs down to 15th place with 15 hours remaining. As a precautionary measure, Team Suzuki Crew Chief Keith Perry decided to use a DOT-spec Dunlop Sportmax Radial up front for the rest of the race.

Team Suzuki’s misfortune allowed Virginia Breeze Racing-a group of fast guys from Summit Point Raceway in West Virginia-to regain the lead, which it briefly held in the first hour of the race. Virginia Breeze had been capable of matching the leaders’ lap times all along, but was having trouble keeping its bike in one piece. “You go out here on these damn bumps and the thing starts vibrating itself to pieces,” said Jim Tribou, both rider and team captain of Virginia Breeze. “Every fourth pit stop you have to repair something minor.” For the next 12 hours the Virginians breezed along in command of the race. Meanwhile, a half dozen or so laps behind them, raged a battle over second place between the Suzuki GSX-R600 Middleweight Superbike of Team Pearls and the Heavyweight Production Yamaha FZR1000 of Force Racing.

In the 20th hour, the winds of change swept Virginia Breeze Racing out of the lead as quickly as it had sailed to the front the evening before. The team’s big Yamaha caught fire following a crash in the Carousel. A turn worker at the scene had righted the fallen FZR without first turning off the ignition switch, and the electric fuel pump spewed gas onto the hot exhaust, which promptly ignited. Another worker arrived with a fire extinguisher, but lost valuable time fumbling with the safety pin.

Even extensive fire damage didn’t divert the determined Virginians, who scrapped the fairing, fitted new carburetors, coils and electrical harness and got their bike back out in a barebones condition. Sadly, their race ended with another crash due to an oil leak suspected to be the result of the fire damage.

Team Pearls, recovering from a crash of its own in the middle of the night, was elated to find itself in the lead. There wasn’t much time for celebration, though, as Force Racing used its FZR’s power advantage to overtake the 600 Suzuki. “I didn’t want to throw it away trying to run them down for first since we had a 13-lap buffer on second-in-class,” said Peter Jones, captain of Team Pearls. “We’d never finished second overall in a race.”

A broken throttle cable during the last 30 minutes of the race put that podium position in serious jeopardy. Team Suzuki Endurance, surviving yet another crash, had by now worked into third overall and was closing fast as Team Pearls lost time in the pits, first for a new cable and then again as the poorly routed replacement cable got hot and started to seize. In the end, time ran out for Team Suzuki Endurance, whose members were grateful to salvage third place. Team Pearls nursed its 600 around the track those final few laps to secure the runner-up slot. Overall winners Force Racing breathed a huge sigh of relief as the checkered flag fell after 24 hours and 2042 miles.

“We had seven riders here so everybody stayed real fresh, that was definitely the key. A lot of other teams, you see riders get off the bike who can’t even walk, and stagger into the pit,” said Ron Crum, rider and crew chief for Force Racing. This marks the team’s 25th endurance win and its first overall victory in a 24-hour. “We have a lot of experience, and that’s what paid off. Everybody kept their heads and did what we had to do,” said Crum.

So is Nelson Ledges really America’s toughest race? Quite possibly. But after 25 years, it definitely will be among the best-remembered.

“This race is truly the endurance race,” says Jim Tribou, who’s been part of four winning teams at Nelson Ledges. “You have to endure not only a rough race track and fatigue, but primitive conditions in the pits. Then you have to get on the motorcycle and ride fast, in fog, avoiding frogs, muskrats, snakes, deer, all sorts of wildlife that comes out of the swamp at night. It’s true punishment, but to win this is to win the grand-daddy of them all. It’s the most gratifying race to win in the country.”

Despite WERA’s withdrawal, there’s a slim possibility the race may carry on. “The 24-Hour existed before WERA and we’ll probably continue the tradition,” said John McGill, a retired U.S. Marine who assumed management of the track in the 1970s. Tribou is less sure, but hopes that the 24-Hour will continue, unsanctioned, a once-a-year event, as he puts it, “strictly for bragging rights” among the Nelson Ledges faithful.

“And I tell ya,” Tribou says, “you win here and you’ve got some serious bragging rights.” □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1993 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1993 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

October 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1993 -

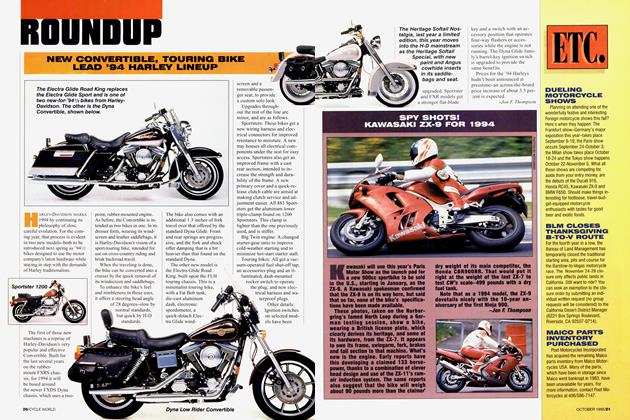

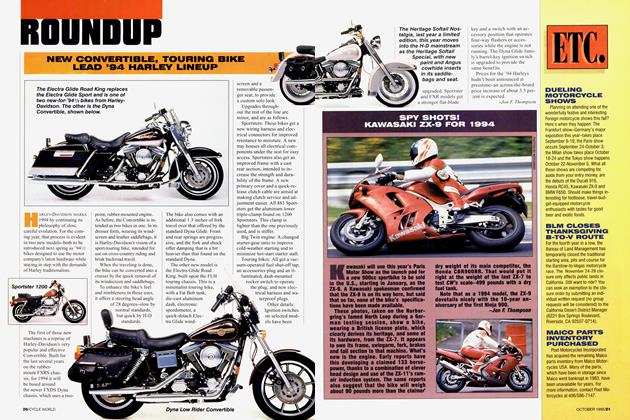

Roundup

RoundupNew Convertible, Touring Bike Lead '94 Harley Lineup

October 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Spy Shots! Kawasaki Zx-9 For 1994

October 1993 By Jon F. Thompson