MAN, BIKE GRAVITY

RACE WATCH

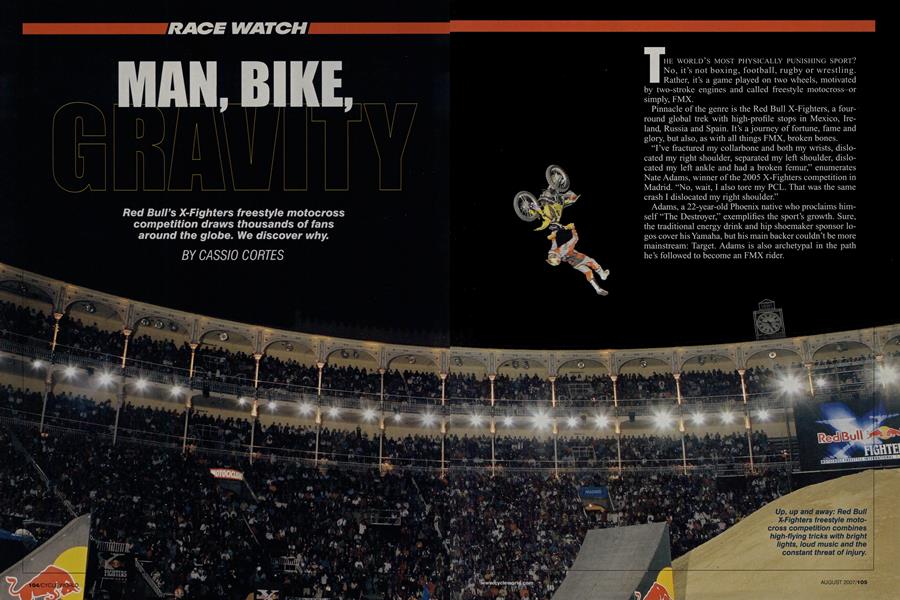

Red Bull's X-Fighters freestyle motocross competition draws thousands of fans around the globe. We discover why.

CASSIO CORTES

THE WORLD'S MOST PHYSICALLY PUNISHING SPORT'? No, it's not boxing, football, rugby or wrestling. Rather, it's a game played on two wheels, motivated by two-stroke engines and called freestyle motocross-or simply, FMX.

Pinnacle of the genre is the Red Bull X-Fighters, a fourround global trek with high-profile stops in Mexico, Ireland, Russia and Spain. It's a journey of fortune, fame and glory, but also, as with all things FMX, broken bones.

"I've fractured my collarbone and both my wrists, dislo cated my right shoulder, separated my left shoulder, dislo cated my left ankle and had a broken femur," enumerates Nate Adams, winner of the 2005 X-Fighters competition in Madrid. "No, wait, I also tore my PCL. That was the same crash I dislocated my right shoulder."

Adams, a 22-year-old Phoenix native who proclaims him self "The Destroyer," exemplifies the sport's growth. Sure, the traditional energy drink and hip shoemaker sponsor lo gos cover his Yamaha, but his main backer couldn't be more mainstream: Target. Adams is also archetypal in the path he's followed to become an FMX rider.

“I began racing motocross back in 1992. Problem was, I was never very good at it,” he admits. “I wasn’t exactly bad, but I was never going to set the world on fire. Freestyle, on the other hand, came easily.” Spaniard Dany Torres, the youngest XFighters competitor at age 19, puts it more simply: “When I raced motocross, what

I liked the most were always the jumps. So why not do only the jumps?”

As a sport that demands a certain dose of irresponsibility, FMX is eerily similar to another formerly niche-oriented form of competition that has spread like wildfire among Generation Y, this one on four wheels: drifting. Besides both being sub-

jective modalities in the overwhelmingly objective, stopwatch-precise universe of motorsport, FMX and drifting have another crucial advantage over their “conventional” counterparts, motocross and roadracing: cost. Adams’ Yamaha YZ250 is nearly bone-stock.

“We change the handlebars, cut down the seats, punch holes on the sides for grab points, add stiffer suspension to handle the landings, put in a freer-flowing exhaust for better throttle response, but that’s about it,” he says.

That ease of access into the specialized world of FMX is better illustrated by someone at the other end of the spectrum to Adams’ Fortune 500 corporate supporters. Brazilian Gilmar “Joaninha” Flores is making, at age 26, his first XFighters appearance. Joaninha-the literal interpretation is “Love Bug”; what nickname could be more appropriate for an FMX rider than a colorful flying insect?-didn’t even bring his own equipment to Mexico.

“The organizers hooked me up with a 2005 model just like the one I use back home,” explains the South American, who earns a living mostly by performing stunts at bike shows that tour Brazil’s country-

side. "I bring my handlebars and a few other parts to feel more comfortable, but that's one of the coolest things about free style-the equipment matters a lot less and

lasts a lot longer than in motocross. Hav ing the most expensive bike won't give you a huge advantage." Flores recognizes he's probably not one

of the 10 best freestyle riders in the world and that his being drafted into the series probably owes as much to adding a Mexi can-fan-friendly Latin rider than to his own

international results. But that, he claims, is no fault of his own; adequate training facilities are woefully lacking in Brazil.

In fact, as the only man in his native country capable of performing a backflip, Flores has been thwarted by the lack of a proper foam pit in which to land his practice jumps. Consisting of a large pool or box filled with foam blocks, these pits are instrumental for a rider to attempt new, unproven moves time and again and still manage to emerge-most times-unscathed. Only days before the Mexico City X-Fighters round, the Brazilian finally finished his own pit in his native city of Sinop near the Amazon forest at a cost of $ 10,000-about V10 of what Adams spent on his pit.

That cost discrepancy is easily explained: “A good foam pit uses non-flammable foam, which is very expensive,” Adams clarifies. “Fve seen a bike catch fire in a pit filled with mattress foam; it turned into a burning inferno like thathe says, snapping his fingers.

“It really sucks that I can’t afford the non-flammable foam,” says Flores, “but to tell you the truth, even finding the regular foam in the quantity I needed was tough. Nobody wanted to send a couple of truckloads of foam all the way to the

Amazon. I know it’s not safe with a hot bike, especially when it’s dripping gas, but what can I do? It’s not like I’m Travis Pastrana.”

And with that we arrive at the man with whom Flores (and nearly every other freestyler in the world) is obsessed. At age 23, Pastrana is the closest thing to a house-

hold name FMX has-hell, to Gen-Y males, he is a household name, a position he solidified with a gravity-defying double backflip during the 2006 X-Games in Los Angeles last August.

To this day, Pastrana remains the only rider to have accomplished this feat. Nobody, including Pastrana, has ever pulled

the trick again-not in competition, not in practice, not for sheer bragging rights before landing upside down in a practice pit. No one. Ever.

“Before foam pits, something like the double backflip was simply impossible," Pastrana says. “In a way, the foam pit has made the sport even riskier, because it’s raised the level of competition dramatically, since you can try so much more stuff.

“But you can’t really call this sport ‘safe’ because of it,” he adds. “Sure, it’s safer than dirt, but I’ve broken a leg and a collarbone falling in foam pits.”

As for the trick that’s raised him to superstardom, Pastrana retains the unassuming attitude that’s marked his every endeavor thus far. “I practiced the double backflip for three years and only once did I manage to pull it off in practice. It was one time in practice, one time in competition, and that’s it. I mean, I crashed in practice seven or eight times trying to pull it off the week before the X-Games.

“I’m sure some of the guys will be double backflipping in the future, but for me it’s just not worth it anymore since my focus is now on rallying,” adds the 2006 Rally America champ, who’s driven

full-time for Subaru of America’s works team since ’05.

How exactly is a double backflip not worth it? “Well, I’ve had 18 surgeries, but that’s not what I’m talking about here,” Pastrana states. “Get this thing wrong and you could die.”

Besides meaning he likely won’t be adding to his double-digit roster of fractures as frequently as in the past, Pastrana’s switch to four wheels-he skipped the 2007 Mexico City X-Fighters round because it clashed with a rally but will return for the final three events-should open up a gap atop FMX’s pecking order. And there’s no lack of pretenders to Pastrana’s throne.

Polesitter in that race is Australian Robbie Maddison. In the media center prior to the opening round of this year’s series in Mexico, “Maddo” is clearly agitated, scrambling for a lost object with the help of five or six others. After the third trash can is turned over, the missing propertyhis front teeth-at last emerges. He’d left the prosthesis next to a computer and it was thrown out, along with a bunch of food wrappers, by an apologetic cleaning lady. Not that the Aussie makes a big fuss about it: a quick napkin-wipe is all

he needs before reinserting the retrieved faux teeth into his mouth.

“I was being stupid in practice a few years ago,” he explains regarding his unique façade. “I was totally jetlagged but riding anyway. I landed hard and flipped. My helmet hit the handlebar, and it pushed the chinbar into my face. No more teeth.”

Getting his incisors knocked out wasn’t all that unusual, though. “I’ve had 25 fractures, one for each year I’ve lived,” he says. “First one was when I was 3, already doing daredevil stuff on my bicycle. I had another one less than a year later on a minibike. Over time, it got to the point the nurses at the hospital would say, ‘Hi, again,’ to my mom and me. I mean, my file had its own drawer.”

Boasting a similar background is Nebraskan Brian Deegan, a 31 -year-old parttime stuntman who’s about to have his own television show on MTV. Deegan claims to have broken every major bone in his body and has insulted every other rider on the circuit (not surprising for someone who lists “building empires” as his hobby). He is also a potential winner of the first-ever X-Fighters world tour trophy, as is Californian Ronnie “Who’s

Your Daddy?” Renner, better known as the man who eroticized FMX-check YouTube and you’ll understand.

Finally, competition night at Mexico City’s Monumental Plaza de Toros is upon us. The opening act comprises 10 riders from seven countries showing up simultaneously to chase a couple dozen “bullfighters” inside the arena, the screaming motorcycles portrayed as mechanized bulls. The sound of 42,000 cheering fans would be deafening if they weren’t drowned out by AC/DC’s “TNT” blaring

at full volume from perhaps the most powerful sound system ever seen (or heard) at a motorsports gathering.

The competition unfolds in the form of preliminary knockout rounds in which two riders go head-to-head, each having 2 minutes to pull off the sickest tricks they can come up with inside the four-ramp arena, which allows for jumps as high as 50 feet. Among the crowd pleasers: “Rock Solid” (rider leaves the bike entirely and fully extends his legs before returning to the seat just in time to land); “Tsunami” (rider performs a handlebar handstand); self-explanatory “Fender Kiss;” and “Lazyboy” (rider lays flat on his back with his hands behind his head). Backflips incorporating no other move (i.e., a “No-

For more on the Red Bull X-Fighters series, visit www.cycleworld.com

Footed Backflip” or a “One-Handed Backflip”) are considered too ordinary at this level. Once the time is up, riders are allowed one final farewell jump, usually their strongest trick.

Five judges decide who progresses on to the semifinals, which are formed by the first round’s five winners plus one “lucky loser,” or the best of the rest. Semifinal winners face off in a three-way final.

The first round’s only surprise is Renner’s loss to Japan’s Eigo Sato, but the Californian would return as the lucky loser. Local favorite Johan Nungaray, a 23-year-old Mexican with a left hand deformed into claw status due to several surgeries (one of which included implanting bones from a corpse to rebuild

his middle finger) is easily handled by Adams, while Flores falls 4-l to defending event winner Mat Rebeaud of Switzerland. The Brazilian is philosophical in defeat: “I’m satisfied because I performed all my best jumps without making any mistakes, and I’ll return home in one piece.”

The most anticipated first-round clash involves Deegan and Torres, only made possible by the Nebraskan’s refusal to practice on the previous day, which seeded him against the Spaniard, who’d posted the top qualifying performance. Although the extension and duration of Torres’ moves are impressive, especially when pulling the “Whip”-a sideways move in which Torres turns the bike nearly 90 degrees in the air before straightening it for landing-Deegan’s demise was in no way guaranteed.

The arena goes quiet in anticipation. Inexplicably, Deegan simply revs the engine of his Honda CR250, hits the ramp at full speed and then climbs off just before the jump, literally throwing his bike into space as if it were a piece of junk. Torres wins 5-0.

Later that night, I asked Deegan why, for crying out loud, he’d wasted his final>

jump. The tattoed rider elucidated what was already clear: “I just don't give a $@#&, dude.”

The semifinals pitch Maddison against Rebaud, Adams versus Sato and Torres opposed to Renner, with the Australian, American and Spaniard progressing to the three-way final. Through the eight duels contested thus far, one thing stands out: All of the winners were perfect, performing their tricks without a hitch. For obvious reasons, FMX is a largely mistake-free sport-when things do go wrong, they go really wrong.

The final reaches a fever pitch, and Torres emerges head and shoulders above the rest. Two minutes are all he needs to land a series of breathtaking moves, including an unbelievable Fleelclicker Backflip, in which both his legs leave the bike and click at the heels while flipping, that earn him a perfect score of 100 and overall victory.

“I watched Maddo and Nate ride, so I knew I had to push it to the limit to beat them,” the youngster celebrates after what he calls the ride of his life. “I can’t wait for the next three rounds.”

Apparently, neither can Adams and Maddo-or Pastrana. “There may have been an element of luck involved in Dany’s victory, but you don’t win X-Fighters by chance,” says Pastrana. “The standard is just too high, and the other riders are too ambitious.”

Pastrana should know. He’s the man who set the standards and whose ambitions have elevated the sport to its current status. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontTen Rest, 2007

August 2007 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsToo Much Bike, Not Enough Road

August 2007 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTales of the Testastretta

August 2007 By Kevin Cameron -

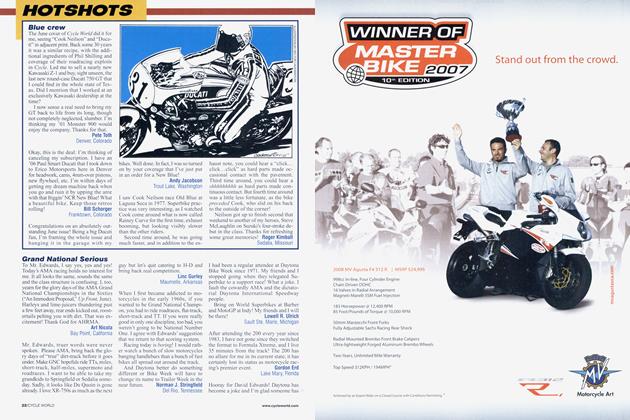

Hotshots

HotshotsHotshots

August 2007 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Tailpipe Chronicles

August 2007 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupCrocker Shocker

August 2007 By David Edwards