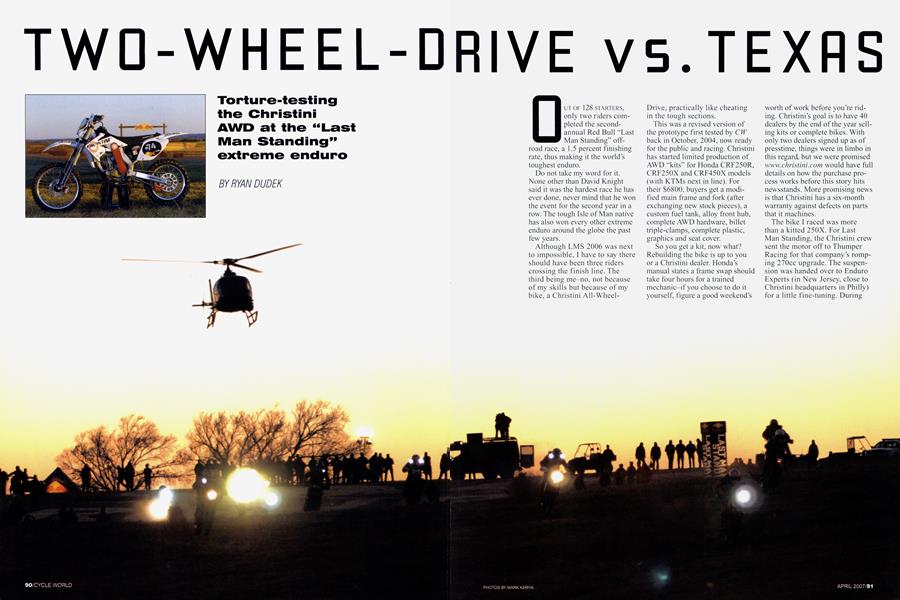

TWO-WHEEL-DRIVE VS. TEXAS

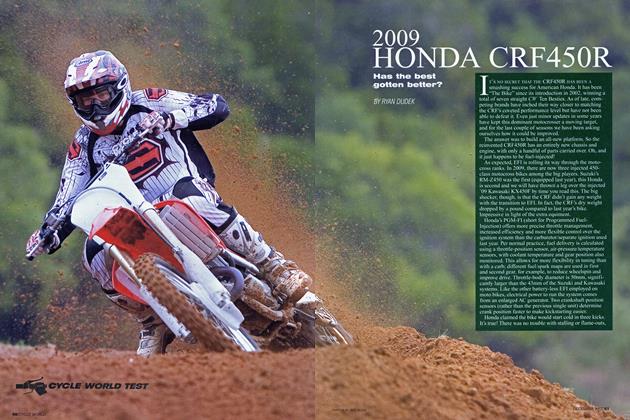

Torture-testing the Christini AWD at the "Last Man Standing" extreme enduro

RYAN DUDEK

OUT OF 128 STARTERS, only two riders completed the second-annual Red Bull "Last Man Standing" off-road race, a 1.5 percent finishing rate, thus making it the world's toughest enduro.

Do not take my word for it. None other than David Knight said it was the hardest race he has ever done, never mind that he won the event for the second year in a row. The tough Isle of Man native has also won every other extreme enduro around the globe the past few years.

Although LMS 2006 was next to impossible, I have to say there should have been three riders crossing the finish line. The third being me-no, not because of my skills but because of my bike, a Christini All-Wheel-

Drive, practically like cheating in the tough sections.

This was a revised version of the prototype first tested by CW back in October, 2004, now ready for the public and racing. Christini has started limited production of AWD “kits” for Honda CRF250R, CRF250X and CRF450X models (with KTMs next in line). For their $6800, buyers get a modified main frame and fork (after exchanging new stock pieces), a custom fuel tank, alloy front hub, complete AWD hardware, billet triple-clamps, complete plastic, graphics and seat cover.

So you get a kit, now what? Rebuilding the bike is up to you or a Christini dealer. Honda’s manual states a frame swap should take four hours for a trained mechanic-if you choose to do it yourself, figure a good weekend’s

worth of work before you’re riding. Christini ’s goal is to have 40 dealers by the end of the year selling kits or complete bikes. With only two dealers signed up as of presstime, things were in limbo in this regard, but we were promised www.christini.com would have full details on how the purchase process works before this story hits newsstands. More promising news is that Christini has a six-month warranty against defects on parts that it machines.

The bike I raced was more than a kitted 250X. For Last Man Standing, the Christini crew sent the motor off to Thumper Racing for that company’s romping 270cc upgrade. The suspension was handed over to Enduro Experts (in New Jersey, close to Christini headquarters in Philly) for a little fine-tuning. During

the build-up, the bike was peppered with aftermarket parts-/, e. an FMF Powerbomb pipe and silencer, Cycra handguards, custom carbon-fiber guards,

TM chain guide, Moose Racing shark fin and an ultra-bright Baja Designs Diablo headlight. Tallied up, my LMS ride was a $16,000 race-ready machine. Yikes!

Unfortunately, I never got to use that trick headlight because I didn’t make it to the second loop, the night portion of the race. But earlier in the day when the Civil War-era cannon A'tf-boomed to mark the start, I was easily in the top 10 entering the hard stuff.

The course was extra-technical, zigzagging up and down massive canyons and snaking through creeks, around trees, over rocks, and thanks to a Texas blizzard two days prior, a lot of the course was covered in ice, which later turned to sloppy mud. And as if that wasn’t challenging enough, a new rule stated that outside assistance was not allowed, except from fellow competitors.

Teamwork, then, became crucial. I made a pre-race pact with one of my longtime racing bud-

dies, Nathan Woods, to help each other if we were stuck near one another. As luck had it, I plopped in right behind him after the bomb run. Most of the first loop went fairly smoothly for Nate and me. There were a couple of sections that hung us up, though Woods, on a Kawasaki KX250, had more trouble than I did. If I got stuck, my driven front wheel simply pulled me out, and I was able to save a ton of energy by not having to push. Nathan is an incredible rider, the 2005 World off-road Championship Series champ, so seeing him struggle over the same terrain that I was clearing with relative ease was a testament to the Christini system.

The setup has not changed much since our first test. A secondary chain runs from a doubled-up countershaft sprocket to a rightangle transfer box, which then turns a small driveshaft that runs under the fuel tank. The shaft turns counter-rotating spiral-bevel gearsets housed inside the steeringhead tube. Power then is transferred to the lower triple-clamp, which contains a small chain and sprocket system that drives two flexible,

telescoping driveshafts running along the fork tubes to the front hub. The shafts rotate in opposite directions to eliminate torque-steer issues.

Sounds complicated (it is), but in use the AWD system is amazing, almost too good to be true. Every obstacle took less effort on my part, the bike literally doing the hard workokay, there was a little skill involved, too. I wasn’t on staff for CWs first Christini test, and from what 1 had been told the system would take some getting used to. Not true; the powered front wheel feels very natural. It does add 15 pounds to the bike, not minuscule by any means. But that weight is spread out evenly and is largely unnoticeable.

Is the system perfect? No. Coming out of turns leaned over hard, the bike wants to stand up quicker than a conventional rear-wheel-drive bike-more of a quirk than a criticism. More problematic, at one point in the race the front wheel started pulling hard to one side. Luckily, there is a shut-off switch that disengages the system. I turned it off and on a bunch of times but the front wheel continued to malfunction. I thought I’d have to finish the rest of the race with rear drive

only, figuring that I’d bent one of the front shafts. But I turned the 2WD back on one last time and the system returned to normal.

When asked what happened, Steve Christini, the wiz behind AWD, said they have encountered this problem before in really mucky conditions. What happens is that mud builds up on one of the exposed upper front driveshafts, causing drag on that shaft and hence torque-steer. Once the mud worked itself clear, the system was back online.

Even with those issues, the AWD setup continued to prove itself. Just past the halfway point, I approached a lengthy uphill while Nathan was coming back down. He waved me on. It took me two tries to clear the top; Woods later said it took him five. I didn’t see Nathan until after the race; unfortunately, after we separated he missed a turn and cut about seven miles off the course, missing the second check, disqualifying him for the second loop.

It was a few miles after that second check where I had my trouble. At the

check, officials said I was in fourth place running 30 minutes behind Knight. Content, I settled into a groove and was motoring along nicely when my rear chain was derailed on a rock ledge-hmmm, I thought the fancy chain guide was supposed to prevent that.

No problem, I figured just slap it back in place and get on with racing. Nope, the errant chain was tightly wedged between the shifter and the engine cases-nothing to do with the AWD system; it could have happened just as easily on a conventional bike.

I took everything apart, including the secondary front-drive chain, but the rear chain still wouldn’t budge. Friendly course workers nearby offered assistance but that, of course, was not allowed. After 45 frustrating minutes, though, I was happy to get the extra help. I was now just trying to get the bike working to make it back to the pits. Three people, a big hammer and punch, and an hour later, I was back in the race.

As I continued on the course, I came to the hardest hill of LMS, “Triple

Threat,” with bikes lined up waiting for an assault. I simply rode around them and went for it, thinking that the sloppy, slimy mud couldn’t defeat the Christini. Wrong. After being abused all day, the clutch on the driveshaft (located on the shaft under the gas tank, there to soften the transfer of power to the front wheel) was slipping and wouldn’t do its full job. A system defect? Yes and no. The clutch problem is an easy fix. It works like a transmission clutch (who hasn’t had problems with those?) and changing it involves a simple swap of plates. Christini said he’s looking into different materials to fix the slipping issue altogether.

Changing clutch plates was not an option on that hillside. No choice but to get help from other racers and then repay the favor; in fact, it took three guys to get each bike up. Not fun!

Of course, David Knight managed to scale the hill all by himself, on his old-fashioned, one-wheel-drive, singleclutch KTM 300 XC. What gives with this guy?! Asked at the finish how he did it, he replied simply, “Aggression.” It also helps that he is 6-foot-4 and apparently stronger than an ox.

Eleven riders made the cut-off for

the second loop-fewer riders than total finishers last year. Unfortunately, I was not one of those riders due to my down

time. I’d houred out and was flagged off the course, never mind that little “outside assistance” infraction. At the end of that second loop, only two riders made it across the finish line, both from the U.K. (What’s in those steakand-kidney pies, anyway?) Wayne Braybrook, Gas Gas-mounted, was runner-up to the Last Man Standing, Knight. Hats off to the promoters for making an enduro that almost lived up to its name, literally.

So, a thumbnail sketch of the Christini AWD? I came away impressed. In loose, rocky, sandy, uphill situations, it’s magic, a real advantage. There’s a reason four-wheel-drive cars rule the off-road world. No, my CRF270X didn’t finish LMS 2006; neither did 125 other bikes.

But if I had just forked out $16,000 on a dirtbike (figure about $13,400 for a straight conversion), I'd want it to be closer to perfect-and at this point, who knows about the long-term durability of the Christini’s many and varied components, to say nothing of its (so far) non-existent dealership network.

I do know this: Two-wheel-drive dirtbikes-and maybe streetbikes, too-are here to stay. The concept is too good to go away. □