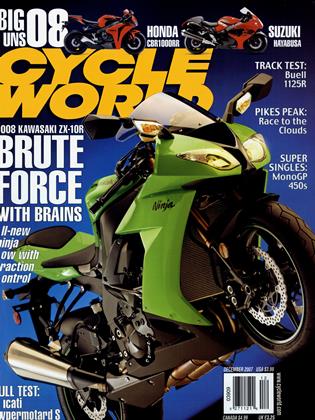

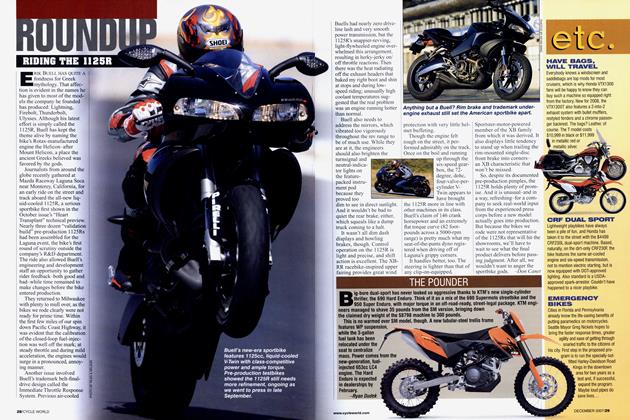

RIDING THE 1125R

ROUNDUP

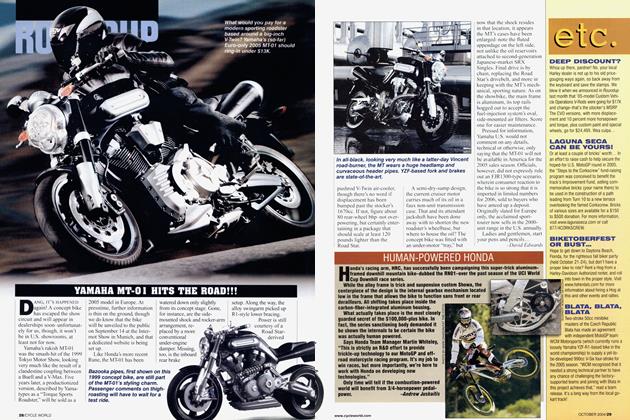

ERIK BUELL HAS QUITE A fondness for Greek Imythology. That affection is evident in the names he has given to most of the models the company he founded has produced: Lightning, Firebolt, Thunderbolt,

Ulysses. Although his latest effort is simply called the 1125R, Buell has kept the theme alive by naming the bike’s Rotax-manufactured engine the Helicon—after Mount Helicon, a place the ancient Greeks believed was favored by the gods.

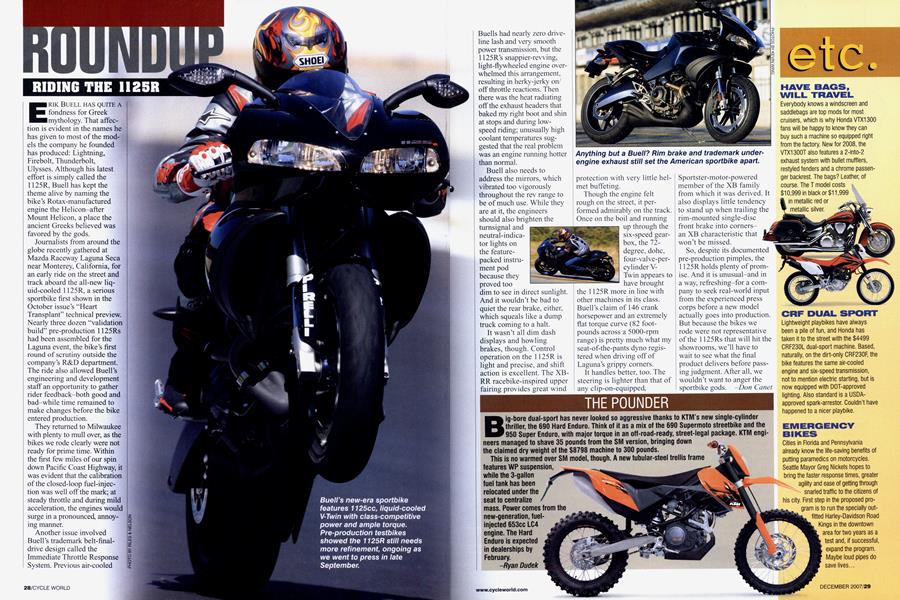

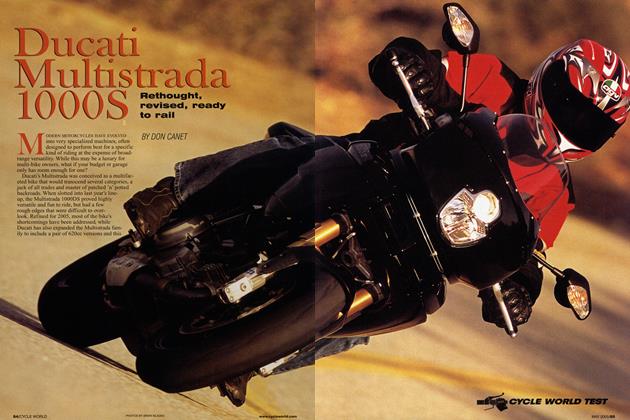

Journalists from around the globe recently gathered at Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca near Monterey, California, for an early ride on the street and track aboard the all-new liquid-cooled 1125R, a serious sportbike first shown in the October issue’s “Heart Transplant” technical preview. Nearly three dozen “validation build” pre-production 1125Rs had been assembled for the Laguna event, the bike’s first round of scrutiny outside the company’s R&D department. The ride also allowed Buell’s engineering and development staff an opportunity to gather rider feedback-both good and bad-while time remained to make changes before the bike entered production.

They returned to Milwaukee with plenty to mull over, as the bikes we rode clearly were not ready for prime time. Within the first few miles of our spin down Pacific Coast Highway, it was evident that the calibration of the closed-loop fuel-injection was well off the mark; at steady throttle and during mild acceleration, the engines would surge in a pronounced, annoying manner.

Another issue involved Buell’s trademark belt-finaldrive design called the Immediate Throttle Response System. Previous air-cooled Buells had nearly zero driveline lash and very smooth power transmission, but the 1125R’s snappier-revving, light-flywheeled engine overwhelmed this arrangement, resulting in herky-jerky on/ off throttle reactions. Then there was the heat radiating off the exhaust headers that baked my right boot and shin at stops and during lowspeed riding; unusually high coolant temperatures suggested that the real problem was an engine running hotter than normal.

Buell also needs to address the mirrors, which vibrated too vigorously throughout the rev range to be of much use. While they are at it, the engineers should also brighten the turnsignal and neutral-indicator lights on the featurepacked instrument pod because they proved too dim to see in direct sunlight. And it wouldn’t be bad to quiet the rear brake, either, which squeals like a dump truck coming to a halt.

It wasn’t all dim dash displays and howling brakes, though. Control operation on the 1125R is light and precise, and shift action is excellent. The XBRR racebike-inspired upper fairing provides great wind protection with very little hel met buffeting.

Though the engine felt rough on the street, it per formed admirably on the track. Once on the boil and running up through the six-speed gear box, the 72degree, dohc, four-valve-per cylinder V Twin appears to have brought the 1 125R more in line with other machines in its class. Buell's claim of 146 crank horsepower and an extremely flat torque curve (82 foot pounds across a 5000-rpm range) is pretty much what my seat-of-the-pants dyno regis tered when driving off of Laguna's grippy corners.

It handles better, too. The steering is lighter than that of any clip-on-equipped,

Sportster-motor-powered member of the XB family from which it was derived. It also displays little tendency to stand up when trailing the rim-mounted single-disc front brake into corners4 an XB characteristic that won't be missed.

So, despite its documented pre-production pimples, the 1 125R holds plenty of prom ise. And it is unusual-and in a way, refreshing-for a com pany to seek real-world input from the experienced press corps before a new model actually goes into production. But because the bikes we rode were not representative of the 1 125Rs that will hit the showrooms, we'll have to wait to see what the final product delivers before pass ing judgment. After all, we 1yr~111r1ti,f iij'~tif tc~ r~cr~r

T~J,Ik~e gods.

Don Canet