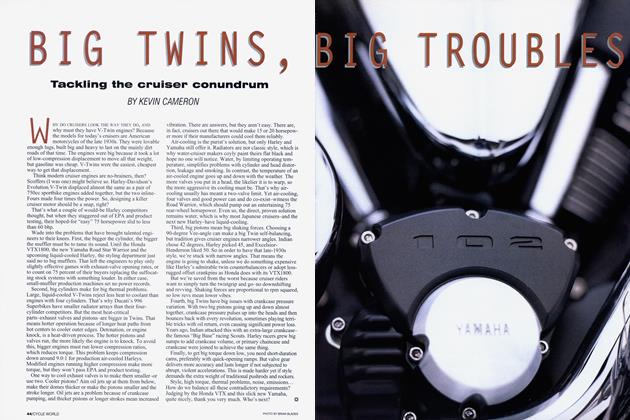

All-conquering?

TDC

Kevin Cameron

LATELY I’VE BEEN LOOKING AT THE HIStory of 500cc Grand Prix racing from the early days. In a 1946 London meeting, the group of national motorcycle clubs that would presently become the FIM decided to initiate a new world championship. Instead of giving championship status to a single race as before, competition in a series would be required. This series would begin in 1949. The passage of decades tends to draw a veil of nostalgia and funhouse-mirror distortion over inconvenient truths. To read some of what is written about the era of dominance by Italian “fire engine” Gilera and MV Fours, you might imagine a golden age in which race after classic race was closely fought, hand-to-hand, by such revered figures as Geoff Duke,

Ordinary motor vehicle gasoline would be the fuel-not the pre-war mixture of best available gasoline with “benzole” (a mix of coal-derived aromatics such as benzene, toluene and xylene). Lacking the presence of fuel with an anti-knock rating high enough to tolerate it, supercharging would be banned. This latter also neatly solved the problem British manufacturers faced in the later 1930s: trying to smoothly supply compressed mixture to J blown single-cylinder engines that naturally took it in huge gulps with long quiet periods between them. The classic solution was to place a “receiver”-a box containing several engine displacements’ worth of volume-between the supercharger and the engine cylinder. If you put the carburetor upstream of the supercharger, this box is full of mixture. If your engine backfires, the whole intake system is sneezed right off the bike-something that was familiar to wartime flyers and postwar air racers alike.

If the carburetor were placed between the receiver and engine cylinder, to get around the above problem, the carburetor float bowl and fuel supply had to be pressurized as well; otherwise supercharger pressure would just blow back through the main jet and bubble up into the float bowl. This could be done, but it was... well, easier solved in that London meeting than in the test houses of the various manufacturers. Besides, Europe and England were a bit tired after all the warring and bombing of the previous six years. Nobody wanted to mess with anything too complicated. Let’s just get our products back into production and maybe fit in a little racing as well.

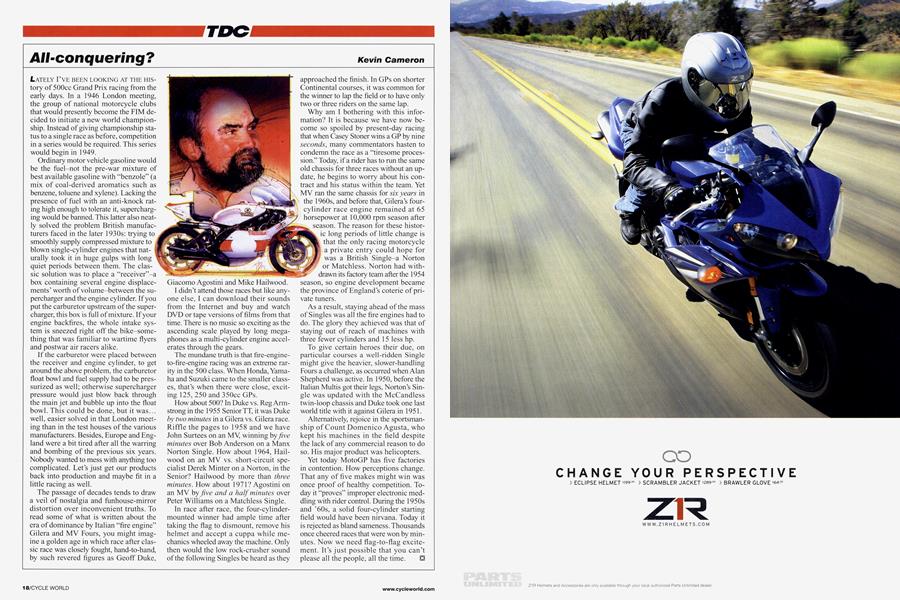

Giacomo Agostini and Mike Hailwood.

I didn’t attend those races but like anyone else, I can download their sounds from the Internet and buy and watch DVD or tape versions of films from that time. There is no music so exciting as the ascending scale played by long megaphones as a multi-cylinder engine accelerates through the gears.

The mundane truth is that fire-engineto-fire-engine racing was an extreme rarity in the 500 class. When Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki came to the smaller classes, that’s when there were close, exciting 125, 250 and 350cc GPs.

How about 500? In Duke vs. Reg Armstrong in the 1955 Senior TT, it was Duke by tw’o minutes in a Gilera vs. Gilera race. Riffle the pages to 1958 and we have John Surtees on an MV, winning by five minutes over Bob Anderson on a Manx Norton Single. How about 1964, Hailwood on an MV vs. short-circuit specialist Derek Minter on a Norton, in the Senior? Hailwood by more than three minutes. How about 1971? Agostini on an MV by five and a half minutes over Peter Williams on a Matchless Single.

In race after race, the four-cylindermounted winner had ample time after taking the flag to dismount, remove his helmet and accept a cuppa while mechanics wheeled away the machine. Only then would the low rock-crusher sound of the following Singles be heard as they approached the finish. In GPs on shorter Continental courses, it was common for the winner to lap the field or to have only two or three riders on the same lap.

Why am I bothering with this information? It is because we have now become so spoiled by present-day racing that when Casey Stoner wins a GP by nine seconds, many commentators hasten to condemn the race as a “tiresome procession.” Today, if a rider has to run the same old chassis for three races without an update, he begins to worry about his contract and his status within the team. Yet MV ran the same chassis for six years in the 1960s, and before that, Gilera’s fourcylinder race engine remained at 65 * horsepower at 10,000 rpm season after season. The reason for these historic long periods of little change is that the only racing motorcycle , a private entry could hope for was a British Single-a Norton or Matchless. Norton had withdrawn its factory team after the 1954 season, so engine development became the province of England’s coterie of private tuners.

As a result, staying ahead of the mass of Singles was all the fire engines had to do. The glory they achieved was that of staying out of reach of machines with three fewer cylinders and 15 less hp.

To give certain heroes their due, on particular courses a well-ridden Single might give the heavier, slower-handling Fours a challenge, as occurred when Alan Shepherd was active. In 1950, before the Italian Multis got their legs, Norton’s Single was updated with the McCandless twin-loop chassis and Duke took one last world title with it against Gilera in 1951.

Alternatively, rejoice in the sportsmanship of Count Domenico Agusta, who kept his machines in the field despite the lack of any commercial reason to do so. His major product was helicopters.

Yet today MotoGP has five factories in contention. How perceptions change. That any of five makes might win was once proof of healthy competition. Today it “proves” improper electronic meddling with rider control. During the 1950s and ’60s, a solid four-cylinder starting field would have been nirvana. Today it is rejected as bland sameness. Thousands once cheered races that were won by minutes. Now we need flag-to-flag excitement. It’s just possible that you can’t please all the people, all the time.